Heart Earth (17 page)

Authors: Ivan Doig

***

It took my father and my grandmother five more years to quit their grievous scrap, but that was a lot better than never.

In the last twist of all, they turned together to raise me. When my father faced himself in the glass door of a phone booth in White Sulphur Springs a night in 1950 and went through with the long-distance call to the Norskie country, he closed down the war that had begun over Berneta and continued over Berneta's child. As my grandmother managed to swallow away as much grudge as she heard being swallowed at the other end of the line, she volunteered herself yet another time into a shortsided situation, never to be a wife nor even a lover, not the mother of me yet something beyond grandparent. From then on, the cook during haying or calving or lambing at the ranches where my father worked was Bessie instead of Berneta, the couple who would throw themselves and their muscles into sheep deals were Charlie and his mother-in-law instead of his young wife. I grew up amid their storms, for neither of these two was ever going to know the meaning of pallid. But as their truce swung and swayed and held, my growing-up felt not motherless but tribal, keenly dimensional, full of alliances untranslatable but ultimately gallant

(no, she's not my mother, she's ... no, he's my father, not my grand-)

and loyalties deep as they were complex. So many chambers, of those two and of myself, I otherwise would have never known.

In the eventual, when I had grown and gone, my grandmother and father stayed together to see each other on through life. April 6, 1971: his time came first, from emphysema which was the cruel lung reprise of my mother's fate. October 24, 1974: my grandmother remained sturdy to her final instantâone mercy at last on these people, her death moment occurred in the middle of a chuckle as she joked with a friend driving her to a card party at the Senior Citizens Club.

Their twenty-one years together, a surprising second life for each, I've long known I was the beneficiary of. The letters teach me anew, though, how desperately far they had to cross from that summer of grief. Theirs was maybe the most durable dreaming of all, that not-easy pair; my father and my grandmother, and their boundaryless memory of my mother.

***

And I see at last, past the curtain of time which fell prematurely between us, that I am another one for whom my mother's existence did not end when her life happened to.

Summoning myselfâsumming myselfâis no less complicated, past fifty, than it was in the young-eyed blur at those howling Montana gravesides.

Doig, Ivan, writer: independent as a mule, bleeder for the West's lost chances, exile in the Montana diaspora from the land,

second-generation practical thrower of flings, emotionally skittish of opening himself up like a suitcase, delver into details to the point of pedantry, dreamweaver on a professional basis

âsome of me is indisputably my father and my grandmother, and some I picked up along the way. But another main side of myself, I recognize with wonder in the reflection of my mother's letters. It turns out that the chosen world where I strive to live full slamâearth of alphabet, the Twenty-Six countryâhad this earlier family inhabitant who wordworked, played seriously at phrase, cast a sly eye at the human herd; said onto paper her loves and her fears and her endurance in between; most of all, from somewhere drew up out of herself the half hunch, half habitâthe have-toâof eternally keeping score on life, trying to coax out its patterns in regular report, making her words persevere for her. Berneta Augusta Maggie Ringer Doig, as distinct as the clashes of her name.

Ivan is fine, growing like a weed,

her pen closes off its last letter ever, June 19, 1945.

You don't need to worry about him forgetting you, he remembers his Uncle Wally and knows what ship you are on. He'll probably have a million questions to ask when you get back.

A million minus one, now. The lettered answer of origins, of who first began on our family oceans of asking. As I put words to pages, I voyage on her ink.

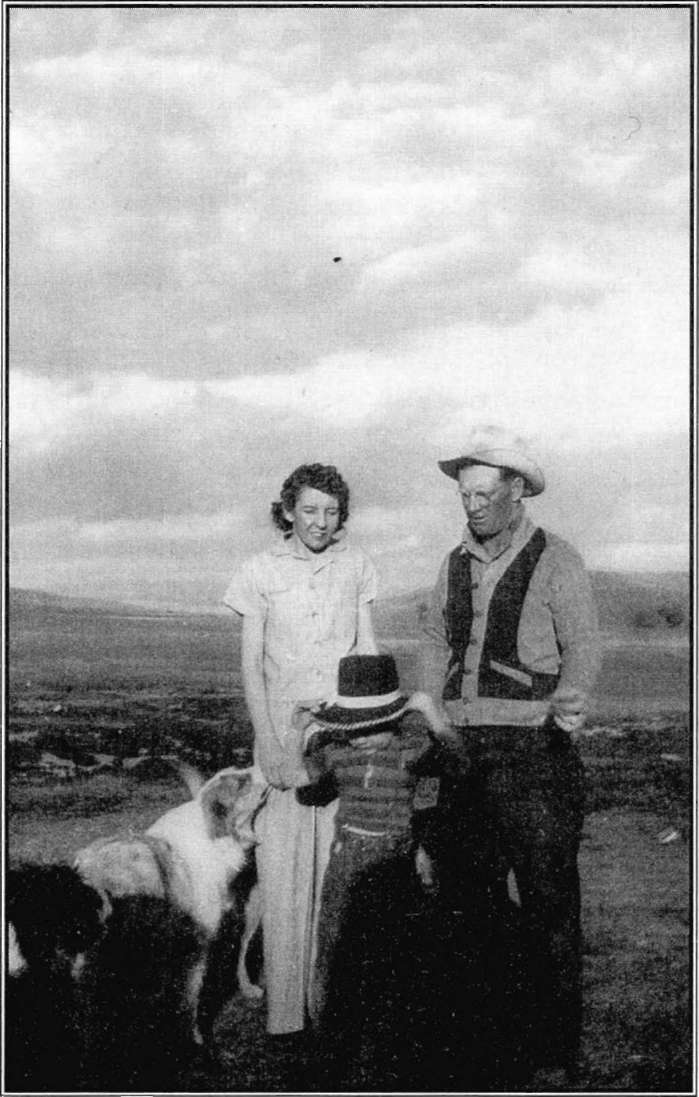

The Doig family, replete with dogs as usual, before leaving Montana for Arizona in 1944.

Carol Doig for her keen eye as a research photographer and manuscript reader, and her customary love and reliability; Dave and Marcella Walter for their knowledge of Montana and its history, and the loan of their four-wheel-drive rig for revisiting the Maudlow country; the late Anna Doig Beetem for details about Alzona Park; the Phoenix Public Library, the Arizona Historical Society, the Arizona Historical Foundation, the libraries of the University of Arizona and Arizona State University, and the Montana Historical Society for backdrop material about Arizona and Montana during World War Two; the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg for information and photos dealing with that community in 1945, and Linda Brown and Rosemary Clark at the Wickenburg Public Library for guiding me through the

Wickenburg Sun

files and other holdings; Elinore S. Thomas of the Corporate Communications Department of the Aluminum Company of America for information about the Phoenix defense plant workforce; Tab Lewis of the Civil Reference Branch of the National Archives for the Defense Plant Corporation floor plan and inventory of the Phoenix plant; Deborah Nash and Nathan Bender of the Merrill G. Burlingame Special Collections at the library of Montana State University, for details of Bozeman in 1945; "Winona" and her husband for their hospitality and talk of the past; the Naval Historical Center, and particularly Bernard F Cavalcante, head of the Operational Archives Branch, for the action reports and war diary of the destroyer USS

Ault,

the National Archives for photocopies of the

Ault

's logbook from Dec. 1, 1944 to Sept. 30, 1945 and for the homestead file of Charlie Rung; David Palmer of Flinders University of South Australia, for the Kearny Shipyard specifications of the

Ault,

Marshall J. Nelson for being Marshall J. Nelson; R. L. Prescott for his memories of Allen and Winnie Prescott; the late Paul Ringer of Rockhampton, Queensland, for his reflective correspondence with me on the family feud between my father and my grandmother; Theresa Buckingham for her recollections of my mother and father, and for her insight on the way my father wore his hat cocked; Linda Bierds for being my volunteer muse on yet another manuscript; Joyce Justice of the Federal Records Center in Seattle, for steering me toward the relevant holdings in the National Archives; the late John Gruar for his recollection of my mother's trapline; Zoe Kharpertian for her deft blue pencil; Liz Darhansoff and Lee Goerner for their usual valuable ministrations in the book bizâ

Heart Earth

and I are grateful to them all.

As is told in this book, Berneta Doig's letters from February to June of 1945 were left to me upon the death of my uncle, Wally Ringer, and I want to particularly thank my cousins, Dan Ringer and Dave Ringer, for searching out and providing me the packet of letters their father wanted me to have. A word about my quotations from the letters herein: I am a writer, not a transcriber, and so when I felt it necessary for clarity of the storyline, I have shifted sentences into an earlier scene than their actual postmark, have taken out an occasional cumbersome bit such as "kind of," and standardized my mother's references to

her

mother as both "Mom" and "Mama" to simply "Mom," to try to lessen confusion. And for the miner's soliloquy on the wagon traffic jam in Deadwood, I have drawn on an early "oral history" interview of freight wagon driver Clarence Palmer, as provided me by the late Vernon Carstensen. As to the German POWs, the frequency of their escapes was even greater than my parents suspected; Arnold P. Krammer in "German Prisoners of War in the United States,"

Military Affairs,

April 1976, points out that "the average monthly escape rate from June 1944 to August 1945 ... was over 100, or an average of 3 to 4 escapes per day."My reference to the "mortal evaporation" that Montana suffered in World War Two is based on the facts that Montanans, in proportion to population, served in the armed forces in numbers higher than the national average, and that Montana's war dead, again proportionally, was exceeded only by New Mexico's among the then-forty-eight states. (Montana also had been hard hit by World War One, when the state's incorrectly high draft call and high voluntarism combined to inflict the highest toll of war dead, proportionally, of all the states.) The specific theaters of combat in which residents of our area, Meagher County, served were compiled from issues of the weekly

Meagher County News;

my uncle's letter from the Pacific and my mother's obituary are both in the July 4, 1945 issue of that newspaper. And finally, the concept of the "Western Civil War of Incorporation," for which I am indebted to the historian Richard Maxwell Brown, his book

No Duty to Retreat

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), and its defining insight that "in the West the incorporation trend resulted in what should at last be recognized as a civil war across the entire expanse of the Westâone fought in many places and on many fronts in almost all the Western territories and states from the 1860s and beyond."