Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire (4 page)

Read Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Peter H. Wilson

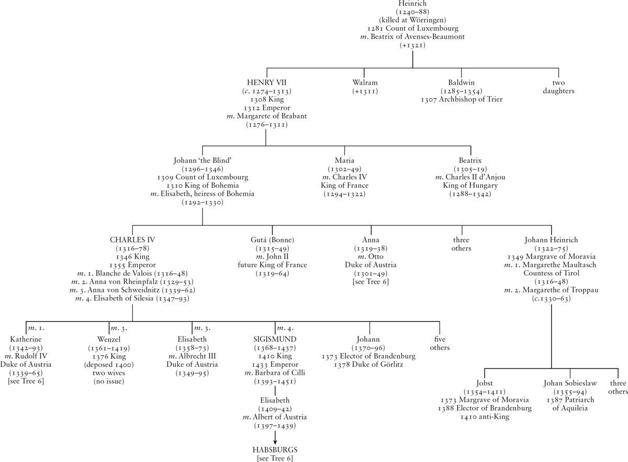

TREE 5: LUXEMBOURGS

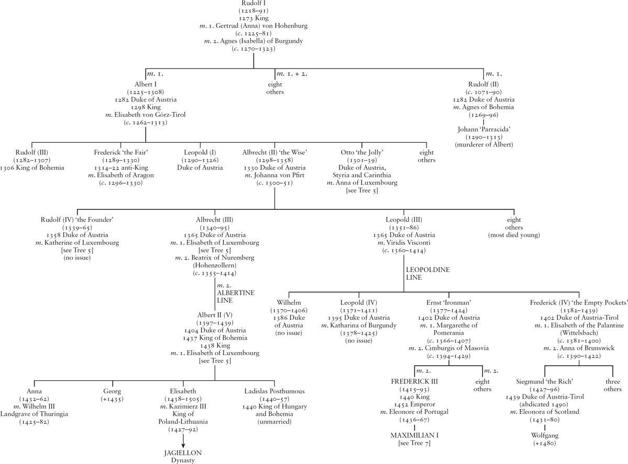

TREE 6: HABSBURGS (Part 1)

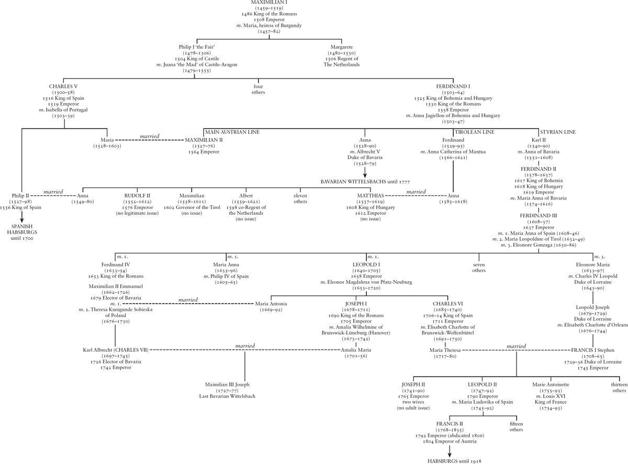

TREE 7: HABSBURGS (Part 2)

Place names and those of emperors, kings and other well-known historical figures are given in the form most commonly used in English-language writing. For east central European locations, this tends to be the German version. Lesser-known individuals are generally identified using the modern version of their names. This at least helps distinguish royalty (e.g. Henry) from aristocracy (e.g. Heinrich) for periods where only a few names predominated amongst the elite. The term ‘Empire’ is used throughout for the Holy Roman Empire, distinguishing this from references to other empires, such as those of the Byzantines and Ottomans. Likewise, ‘Estates’ refers to corporate social groups, like the nobility and clergy, and to the assemblies of such groups, whereas ‘estates’ identifies land and property. The Empire endured throughout the periods when it was ruled by a king who had not been crowned emperor. Use of the terms ‘king’ and ‘emperor’ reflects the status of the Empire’s monarch at any given period. Foreign terms are italicized and explained at first mention, generally with additional information provided in the glossary. Terms and their definitions can also be accessed using the index.

This book would have been impossible without the kind assistance of numerous good people. I am particularly grateful to Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger and Gerd Althoff for their kind hospitality and lively critique of my ideas during my time as visiting fellow at the Excellence Cluster at Münster University. My colleagues Julian Haseldine and Colin Veach, as well as Simon Winder at Penguin, read and commented on the entire book, offering innumerable insightful comments and suggestions. Additionally, I have benefited from long discussions on all or parts of what eventually became this book with Thomas Biskup, Tim Blanning, Karin Friedrich, Georg Schmidt, Hamish Scott, Siegfried Westphal and Jo Whaley. Virginia Aksan, Leopold Auer, Henry Cohn, Suzanne Friedrich, Karl Härter, Beat Kümin, Graham Loud and Theo Riches all kindly sent useful material or pointed me in the direction of books I had overlooked. Rudi Wurzel and Liz Monaghan of the Centre of European Union Studies at the University of Hull provided me with an opportunity to test out ideas before an interdisciplinary audience, which help give shape to the concluding chapter. Some elements of the introduction and conclusion were presented at a conference on the Reichstag at the University of Regensburg, for which I am especially grateful to Harriet Rudolph.

The University of Hull provided a semester’s research leave during which the book assumed its general shape, while the staff of the Brynmor Jones Library performed miracles in locating obscure literature that I needed to use. Cecilia Mackay tracked down my picture requests with her customary efficiency, while Jeff Edwards transformed my sketches into beautiful maps. Richard Duguid expertly oversaw the book’s production. Richard Mason’s eagle-eyed copy-editing saved me from innumerable potential errors, and the proofreading of Stephen Ryan and Michael Page was invaluable. I am also grateful to Kathleen McDermott and the staff at Harvard University Press for putting the book into production in the US. As always, Eliane, Alec, Tom and Nina have contributed to my work in more ways than they know, for which I am eternally thankful.

The Holy Roman Empire’s history lies at the heart of the European experience. Understanding that history explains how much of the continent developed between the early Middle Ages and the nineteenth century. It reveals important aspects which have become obscured by the more familiar story of European history as that of separate nation states. The Empire lasted for more than a millennium, well over twice as long as imperial Rome itself, and encompassed much of the continent. In addition to present-day Germany, it included all or part of ten other modern countries: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland and Switzerland. Others were also linked to it, like Hungary, Spain and Sweden, or involved in its history in often forgotten ways, such as England, which provided one German king (Richard of Cornwall, 1257–72). More fundamentally, the east–west and north–south tensions in Europe both intersect in the old core lands of the Empire between the Rhine, Elbe and Oder rivers and the Alps. These tensions were reflected in the fluidity of the Empire’s borders and the patchwork character of its internal subdivisions. In short, the Empire’s history is not merely part of numerous distinct national histories, but lies at the heart of the continent’s general development.

This, however, is not how the Empire’s history is usually presented. Preparing for the Continental Congress that would give his country its constitution in 1787, the future US president James Madison looked to Europe’s past and present states to build his case for a strong federal union. Reviewing the Holy Roman Empire, then still one of the largest European states, he concluded it was ‘a nerveless body; incapable of regulating its own members; insecure against external dangers; and

agitated with unceasing fermentation in its own bowels.’ Its history was simply a catalogue ‘of the licentiousness of the strong, and the oppression of the weak . . . of general imbecility, confusion and misery.’

1

Madison was far from alone in this opinion. The seventeenth-century philosopher Samuel Pufendorf famously described the Empire as a ‘monstrosity’ because he felt it had degenerated from a ‘regular’ monarchy into an ‘irregular body’. A century later, Voltaire quipped it was neither holy, Roman nor an empire.

2

This negative interpretation was entrenched by the Empire’s inglorious demise, dissolved by Emperor Francis II on 6 August 1806 to prevent Napoleon Bonaparte from usurping it. Yet this final act itself already tells us that the Empire retained some value in its last hours, especially as the Austrians had already gone to considerable lengths to prevent the French from seizing the imperial regalia. The Empire would be plundered when later generations wrote the stories of their own nations, in which it appears positively or negatively according to the author’s circumstance and purpose. This trend has grown more pronounced since the later twentieth century, with some writers proclaiming the Empire as the first German nation state or even a model for greater European integration.

The Empire’s demise coincided with the emergence of modern nationalism as a popular phenomenon, as well as the establishment of western historical method, institutionalized by professionals like Leopold von Ranke who held publicly funded university posts. Their task was to record their national story, and to shape it they constructed linear narratives based around the centralization of political power or their people’s emancipation from foreign domination. The Empire had no place in a world where every nation was supposed to have its own state. Its history was reduced to that of medieval Germany, and in many ways the Empire’s greatest posthumous influence lay in how criticism of its structures created the discipline of modern history.

Ranke established the basic framework in the 1850s which others, notably Heinrich von Treitschke, popularized over the course of the next century. The Frankish king Charles the Great, who was crowned first Holy Roman emperor on Christmas Day 800, appears in this story as the German

Karl der Grosse

, not the Francophone

Charlemagne

. The partition of his realm in 843 is interpreted as the birth of France, Italy and Germany, with the Empire thereafter discussed in terms of

repeated, thwarted attempts to construct a viable German national monarchy. Individual monarchs were praised or condemned according to an anachronistic scale of ‘German interests’. Rather than entrench the imperial title in Germany itself as the basis of a strong, centralized monarchy, too many monarchs, it seemed, pursued the pointless dream of re-creating the Roman empire. To rally support, they allegedly dissipated central power in debilitating concessions to their senior lords, who emerged as virtually independent princes. After several centuries of heroic efforts and glorious failures, this project finally succumbed in a titanic clash around 1250 between German

Kultur

and the treacherous Italianate civilization represented by the papacy. ‘Germany’ was now condemned to weakness, divided by the dualism between an impotent emperor and selfish princes. For many, especially Protestant writers, the Austrian Habsburgs wasted their chance once they obtained an almost permanent monopoly of the imperial title after 1438, by again pursuing the dream of a transnational empire rather than a strong German state. Only the Prussian Hohenzollerns, emerging on the Empire’s north-eastern margins, carefully husbanded their resources, preparing for their ‘German mission’ to reunite the country as a strong, centralized nation state. Although shorn of its nationalist excesses, this story still continues as the ‘basso continuo’ of German historical writing and perception, not least because it appears to make sense of an otherwise thoroughly confusing past.

3

The Empire took the blame for Germany being a ‘delayed nation’, receiving only the ‘consolation prize’ of becoming a cultural nation during the eighteenth century, before Prussian-led unification finally made it a political one in 1871.

4

For many observers this had fatal consequences, pushing German development along a deviant ‘special path’ (

Sonderweg

) away from western civilization and liberal democracy and towards authoritarianism and the Holocaust.

5

Only after two world wars had discredited the earlier celebration of militarized nation states did a more positive historical reception of the Empire emerge. The concluding chapter of this book will return to this in the context of how the Empire’s history is being used to comment on and inform discussions of Europe’s immediate future.

The term ‘empire’ requires some clarification before proceeding further. The Empire lacked a fixed title but was always referred to as imperial, even during the long periods when it was governed by a king

rather than an emperor. The Latin term

imperium

was gradually displaced by the German

Reich

from the thirteenth century. As an adjective, the word

reich

means ‘rich’, while as a noun it means both ‘empire’ and ‘realm’, appearing in the terms

Kaiserreich

(empire) and

Königreich

(kingdom).

6

There is no universally accepted definition of an empire, though three elements are common to most interpretations.

7

The least useful is a stress on size. Canada covers nearly 10 million square kilometres, over 4 million square kilometres larger than either the ancient Persian empire or that of Alexander the Great, yet few would contend that it is an imperial state. Emperors and their subjects have generally lacked the obsession of social scientists with quantification; on the contrary, a more meaningful defining characteristic of empire would be its absolute refusal to define limits to either its physical extent or its power pretentions.

8