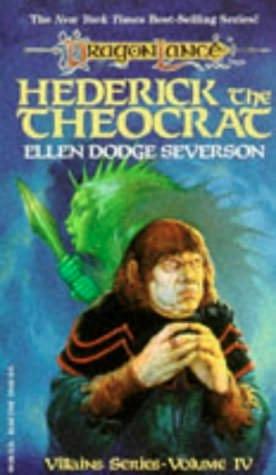

Hederick The Theocrat

Dragonlance - Villains 4 - Hederick The Theocrat Severson, Ellen Dodge

This book is lovingly dedicated to the memory of William Olm and Max Earl Porath

Astinus, leader of the Order of Aesthetics, surveyed the three apprentice scribes before

him. The historian's face, as usual, wore the expression of a man taken unwillingly from

his beloved work for something annoyingly trivial. The three scribes, a middle-aged woman

and two younger men, shifted from foot to foot beneath his gaze and darted cautious

glances at each other. Each was sure the other two possessed extraordinary training and

expertise. Each was sure that it was his or her mere presence in the Great Library

ofPalanthas that had brought the dissatisfied gleam to Astinus's eyes. They all were

convinced that their own appointments as apprentices to the premier historian on Krynn

would soon be found to be a mistake. All that work, all those years of preparation and

study, would be found inadequate. They were unworthy. Each steeled for disappointment,

afraid of being sent home in humiliation to become a store clerk or street vendor.

In truth, Astinus was not annoyed with the apprentices but merely anxious to be back at

work, writing down the history of Krynn as it occurred. Even as he stood here assessing

the guarded expressions of these three, details of fact were going unrecorded in the

scrolls of the Great Library. It was difficult to catch up once one was behind, as Astinus

knew only too well; it was almost better to skip what one had missed in one's absence and

go on to pen whatever was happening at the moment. Unlike the other scribes, who worked in

shifts, Astinus had never been known to sleep or to step away from his work for more than

a few minutes. There were some among his helpers who whispered that Astinus was no mortal,

for hadn't his name been found upon scrolls dating back thousands of years? Unless, they

speculated, every chief historian's name, since the beginning of time, had been Astinus.

Actually, Astinus was well-pleased with this crop of apprentices. These three, however

they quailed before him now, had come on the highest recommendations of Astinus's

far-flung advisers. They needed only seasoning, he'd been told, before they could take

their places among Astinus's dozens of assistants in the Order of Aesthetics.

What was needed was a task that would test their ability to cooperate as well as to

chronicle history, Astinus thought as the three suffered silently before him. It must be

something, of course, that the historian could check for accuracy against his own

knowledge of events as they unfolded. He narrowed his eyes and nodded as he surveyed the

trio. “Hederick,” he murmured. “That's it.” The scribes exchanged more glances, each

wondering which of the others was named Hederick.

“Sir?” the middle-aged woman finally ventured. She had the pale ashen complexion common

among those who spent their lives prowling through the dimly lit corridors of libraries.

She was of medium height and average build and wore her brown hair gathered with a simple

length of blue yarn at the nape of her neck. She wore the same type of sleeveless,

togalike outfit that the other two woreindeed, that Astinus himself wore. “Sir,” she said

again hesitantly, “is there something we...?” The remaining two apprentices lost no time

interrupting the woman's query. In this competition for a coveted position in the Great

Library ofPalanthas, none wanted to be left at the starting line. “You have a task for us,

master?” broke in the younger of the two men, a tall, red-haired youth with creamy skin,

copious freckles, and blue eyes. “We stand waiting to serve you,” interjected the other

man. He had eyes as black as his curly hair and skin the color of cinnamon, marking a

sharp contrast to the youth beside him. Suddenly, all three apprentices were speaking at

once. A new frown descended over Astinus's already stern features, and the three

apprentices faltered in their chatter. “You are delaying me,” Astinus declared in

irritation. “Give me your names, quickly, that I may sort you out and assign you tasks.

And be brisk about it.”

“Marya,” replied the woman. “Olven,” the dark-haired man said proudly. “Eban,” the

redheaded youth answered last. “Fine,” Astinus said, noting their names for inclusion in

his history of the Great Library. “Your task, then, is this: to chronicle the doings of a

man named Hederick, recently named High Theocrat of Solace. I believe the scheming of this

man will someday have great import in Krynn.” His penetrating stare raked the three

aspiring historians. “First you will research Hederick's past and set it out. You, Eban,

will take charge of that.” The youth stood up straighter and cast a triumphant look toward

the other two. Astinus went on, “All of you are students enough to grasp that without

knowing a man or woman's past, it is impossible to understand that person's present.” “Oh,

yes,” said Eban. “Certainly,” Marya chimed. “Without a doubt,” Olven added. “You

two”Astinus thrust his chin at Marya and Olven “will concentrate on recording the present

exploits of High Theocrat Hederick.” He pointed to a wooden desk in the corner of the

library. “One of youand you, too, Eban, when you complete your researchwill be seated at

that desk at all times, day or night. This spot must never be empty.” Three pairs of eyes

widened, but the historian continued speaking regardless of their surprise. “History

occurs in times of darkness as well as at noon, as you all know. Even now, events are

sweeping on unrecorded as you dally here.” Eban gasped and swept up a scrap of parchment

and a quill pen from a counter. He scurried between two stacks of books and was gone.

Astinus marked the red-haired youth's industry. Surely the background material would be

ready soon at that pace, he thought with satisfaction. Astinus made his way to the door of

the Great Library. “I leave it to you to decide how you will divide the day,” he said over

his shoulder to Marya and Olven. “Whoever is not recording currently transpiring events

should help Eban with his research, for that must go first in your written account, of

course. Now I must return to my tasks.” “Ah... sir?” Olven said quickly. “A question?

Quickly?” Astinus halted, his hand on the doorjamb. Olven cleared his throat and looked

embarrassed. “How will we know what's happening now, so that we may record it?” the man

asked. “After all, it hasn't been written down anywhere yet,” Marya added helpfully. “And

it appears that you want us to stay here. In the library, I mean.” Astinus,

expressionless, gazed at the two for a long, silent moment, then the briefest of smiles

crossed the historian's face. “Sit at the desk,” the historian said. “You will see, soon

enough. If you are meant to work here.” Then he was gone. Marya looked at Olven, who gazed

back at her. They both swiveled about to thoughtfully survey the padded chair drawn up

before the desk. “It looks ordinary enough,” Marya said in a small voice. Just a chair.

Olven nodded. “Magic, do you think?” he whispered “Has Astinus ensorceled us without our

knowledge?” Marya shrugged, but swallowed twice before going on Maybe. You go first."

Olven bit his lips, took a deep breath, and slid into the chair.

The scream invaded Hederick's very bones and blood, coming from nowhere and everywhere.

The sound reverberated again. Hederick raced across the prairie toward a grove of trees,

where his sister Ancilla had hidden ten years earlier. He was still quite a distance

awaytoo far, by the god Tiolanthe! Feet pounded behind him, and with them, thunderclap

after thunderclap from the approaching storm. Time after time, Hederick stamped on jagged

rocks and stumbled over upthrust roots. Bloodstained footprints marked his passage. Then

trees loomed. Hederick dove into Ancilla's Copse as though it were a church and Hederick a

penitentas though whatever tracked him dared not enter such a holy place. His lungs

burned. His ribs ached. The boy landed facedown in soft dampness and tensed for the cry

that would tell him the creature was upon him. But there was silence; only an intermittent

popping sound broke the hush of the glade. Hederick sat up warily and peered around in the

flickering light. Large trees with rough bark towered over him, interspersed with saplings

that thrust upward through the ferns. The rich smell of hickory mingled with the odors of

fragrant moss and moist soil. Surrounded by dark shapes that seemed to dance in the wind

of the approaching storm, the boy fearfully scanned one shadow after another. The yellow

eyes of a gigantic lynx glared at him. The dappled brown beast was easily ten feet from

nose to bobbed tail. The great cat crouched fifteen feet above him, wedged in the crotch

of a tree. Its eyes were enormous, forelegs heavy, padded feet huge. Thunder shattered.

The lynx and Hederick screamed at the same instant. “Begone!” A sword appeared above the

boy, interposed between his crouching body and the giant predator. Red light played on the

weapon's edge. A gauntleted hand grasped the hilt; an arm corded with muscular sinew held

the blade steady. Hederick sat, powerless with fear. The lynx screamed again, and the hand

tightened on the hilt. “Leave us, cat!” came that same booming voice. The lynx tensed to

spring, and the man swore fervently, invoking gods Hederick had never heard of. Just as

the giant feline leaped, the man's other hand swept up, raising a flaming torch. Light

exploded. Red and yellow sparks burned pinpricks into the ferns. The lynx twisted away in

midleap and crashed through a maple sapling and onto the ground off to one side. The man

dropped the torch and whirled to meet the cat, sword ready, his body between the boy and

the lynx. Then Hederick was up. His left hand caught up the sputtering torch from the wet

moss, and he ran to the man's side, bellowing a battle cry. Hederick threw anything and

everything his right hand could grasp. Rocks, branches, leaves, mud, mossall were hurtled

toward the snarling lynx. His tall rescuer remained poised with his sword. “By the New

Gods, the boy's feisty!” the man said. The only thing left was the torch; Hederick

prepared to throw that as well. The man swore again, fumbled at his belt, and tossed

something at the cat just as the boy released the fiery brand. Another explosion of

scarlet and topaz flashed through the trees. Bigger and louder than the last, it knocked

Hederick flat on his back. When the smoke cleared, there was no sign of the lynx. “Did we

kill it?” Hederick could barely get the words out. His tongue seemed stuck to the roof of

his mouth. The man sheathed his sword and laughed uproariously, then shook his head. “By

the New Gods, that pussycat must be halfway to the Garnet Mountains by now! If her feet

touch the ground every six furlongs, if 11 be a miracle.” Hederick shook uncontrollably.

Blood streamed into his eyes from a cut on his forehead. "It's still

out there?“ he wailed. ”It's not dead?“ ”Not dead, lad, but she won't be coming back here

soon.“ The man extended a hand to help the boy up. Hed-erick's knees shook so that he

could barely stand. ”I can't imagine what the she-cat was doing so far from the Garnets,“

the man mused, ”but who knows how great a distance the creatures travel to hunt? Perhaps

she sought food for kits.“ ”But it was hunting me!“ Hederick shrieked. The man shrugged.

”You escaped.“ Wordless, Hederick studied his rescuer. The man couldn't have been much

more than twenty. His face was long, with a dark beard neatly trimmed to a point and gray

eyes that seemed both humorous and kind. A rough brown robe stretched to cover powerful

shoulders. The man submitted to Hederick's frank inspection without embarrassment. ”By

Ferae, you're a small one! How old are you? Eight? Nine?“ ”Twelve,“ Hederick muttered.

”Your name, son?“ ”Hederick.“ ”I'm Tarscenian,“ the man said. ”Let me invite you to

supper, young Hederick.“ Tarscenian placed a strong arm about the boy's still trembling

shoulders and guided him deeper into the grove, where a small campfire blazed cheerily.

The fire popped as they approached, the sound Hederick had heard as he entered the copse.

Tarscenian urged the boy to sit against a fallen log and handed him a wooden trencher.

Three pieces of meat swam in greasy juice. ”You can dine like a theocrat on fresh roast

rabbit,“ Tarscenian said, ”and then tell me how in the name of the Lesser Pantheon you

ended up alone in the middle of nowhere.“ Soon Hederick had all but licked the trencher

clean. The hare's picked bones blackened in the fire. Tarscenian lounged on a blanket

across from the boy, watching with amazement. ”Whatever you take on, lad, whether it's

lynxes or supper, you certainly do it wholeheartedly,“ he commented. Hederick bristled.

The man had offered him dinner. What was he supposed to doadmire it until it congealed?

The man laughed and held up his hand. ”Calm down, lad. I mean you no insult. You showed

more spirit in facing that she-lynx than many full-grown men would have.“ Mollified,

Hederick leaned back against the log, regarding his rescuer with awe. Tarscenian was a far

cry from the men of Hederick's isolated home village of Garlund. The young man's eyes

glittered with life, his gaze was direct, and his movements vigorous. If the god Tiolanthe

ever took human form, he would look like Tarscenian, Hederick decided. ”So, Hederick, what

were you doing alone on the prairie in the dark of night?“ the stranger asked. ”Assuming

that you weren't hunting lynxes, that is.“ Tarscenian listened with growing astonishment

to the boy's story. Hederick told him about his mother and father, Venessi and Con, who,

after walking for weeks due east from their home city of Caergoth, had founded the village

of Garlund just south of Ancilla's Copse. Their purpose was to provide a place where they

and their followers could worship Tiolanthe, the god that regularly appeared to Venessi

and Con, but only to them. Then Hederick had been born, the first baby delivered in the

new village. Two years later, when Con disagreed with Venessi over some matter of

Tiolanthean doctrine, Hederick's mother had ordered the people of the village to kill her

husband. Hederick's sister Ancilla, fifteen years his senior, had fled Garlund moments

after Con's death. ”She promised to return for me, but she never did,“ Hederick said

simply. Tarscenian interrupted only oncewhen the storm broke and the pair took shelter

under oiled canvas stretched from tree to tree. Each sat wrapped in a gray woolen blanket

that smelled of incense and horsehair. Hederick talked until he could barely put words

together, he was so sleepy. ”And now I've been banished,“ Hederick said, ”by Venessi.“

”Your mother sent a twelve-year-old into the prairie alone at night?“ Tarscenian demanded

with a frown. ”I must learn humility, she said,“ Hederick explained, his words slurring.

”And then the lynx came after me, and I ran to the only place I could think ofAncilla's

Copse. This is where Ancilla hid when she left Garlund, when I was two."

“You must not remember very much about this sister,” Tarscenian said sympathetically. “Oh,

no!” Hederick exclaimed, shaking himself awake. “I remember her well. She had eyes as

green as grass, and she was prettyoh, so pretty, Tarscenian. She knew all about plants and

herbs and things, and when Con beat me for sinning, she would give me things to take away

the pain. Ancilla was wonderful.” “But then she left.” Hederick's face fell, and he

nodded. “She was afraid the villagers would kill her as they had killed our father. So she

left. And then she forgot all about me. I... I guess I was too sinful to come back for.”

He remembered the night before Ancilla had left. For some minor infraction, Con had beaten

young Hederick mercilessly. Ancilla, achingly beautiful at seventeen, defended him and

treated his wounds. Hederick had begged her to stay with him. “You won't ever stop being

my sister, will you?” he'd cried. “Close your eyes, little brother,” Ancilla had answered,

rocking him by the fire. The little boy, safe in the comfort of his sister's arms,

resisted sleep. She murmured words Hederick had never heard before, tenderly stroking his

face and wispy reddish-brown hair. She fed him cold tea from a spoon, and when he tried to

speak again, covered his mouth with a gentle hand and hushed him. Once she rearranged the

blanket to cover Hederick's feet, then she spoke fiercely. “I promise you this, little

Hederick: I will always be your sister. / will never hurt you. I will protect you with

every power I have. I will do all I can, even from afar, to keep Con and Venessi from

turning you into ... into what they are. You need never fear me. That I vow.” That memory

was too holy to share with this stranger, however. And besides, Hederick was so tired; he

felt himself sinking into sleep. Then Tarscenian's voice roused him. “This village of

yours, is it large?” the stranger asked. “Large and wealthy?” Hederick shook himself

awake. “Sixty people, maybe.” “Prosperous?” the man asked. “Venessi has plenty of food

stored in the barns, but the people don't know that. They're restricted to two meals a

day. No one in the village is well-fed except my mother, but she's in Tiolanthe's graces.

Other than the food, there's nothing but a few candlesticks in the prayer house, and some

icons.” “Steel icons?” Tarscenian asked quickly. Since the Cataclysm, steel had been the

most precious metal on Krynn. Hederick nodded. Tarscenian didn't speak for a while, and

Hederick thought he'd fallen asleep. The boy had nearly followed suit when the man's deep

voice resounded again. “Lad,” he said, “I believe it's time for me to rest in my travels.

And it's time the people of Garlund learn about some new gods.” Hederick jerked upright,

bumping the oiled canvas and sending a splash of cold water down his left leg. “New gods?”

Tarscenian smiled impishly and extended his blanket to cover the boy's soaked leg. “You've

not asked me about myself, lad.” The man had rescued Hederick from a lynx and given him

dinner ... and listened to his long tales. Wasn't that enough to know about someone?

“You're a trader,” Hederick said. “Or a mercenary.” “I'm a Seeker priest.” A priest!

Hederick struggled to his knees. The blankets snared him around the ankles, and he tore at

them with clumsy fingers. He didn't know what a Seeker was, but no matter. The man was a

heathen and a priest! “I speak for the New Gods, son.” “No!” Hederick shouted angrily,

feeling betrayed by the man he'd begun to think of as a hero. “There is only one god. The

Old Gods deserted us in the Cataclysm, and every god since then is just pretend, except

for Tiolanthe. He speaks to my mother. And I'm not your son, you fraud.” Tears

streamed down his cheeks. Tarscenian carefully gauged the boy's heated denial. Some of the

friendliness left the gray eyes. “Who do you think saved us from the she-lynx, Hederick?

Who frightened her off ... me? You and your clods of moss? Some higher power? Or this

Tiolanthewhile we're speaking of frauds?” Hederick refused to look at him. “You did,” he

said sulkily. “You had the sword.” Tarscenian cocked his head. “My blade never touched the

lynx, son. And what about the explosions?” Hederick had no answer. Tarscenian's hand

locked around the boy's thin wrist, pulling him near. “The New Gods interceded, Hederick,”

the priest said gently. “Can your mother do that, by calling on her god? Can this

Tiolanthe himself, for that matter?” “N-no,” Hederick mumbled. “Well, then, perhaps the

New Gods have a plan for you, son.” Tarscenian's voice grew insinuating. “Perhaps I'm a

part of that plan. Who are we to question the will of the gods?” Hederick risked an upward

glance. Tarscenian's gray eyes were direct; the friendliness was back. And yet... “What do

you take me for, a fool?” Hederick exclaimed suddenly. “I'm no part of a plan___” He

crawled out from under the canvas. Tarscenian surprised him by letting him go-Rain lashed

at the boy, and in moments he was soaked. A few steps away, the campfire still flickered

under a scrap of suspended canvas, but Hederick was determined not to return to

Tarscenian's sanctuary. Lightning erupted. Thunder crashed through the trees. “Where will

you go, lad?” “Home!” Hederick said desperately. “My... my mother will be worrying about

me in this storm.” Tarscenian said nothing for a few moments. Hederick's words hung

between them. “From the sounds of it, lad, your mother worries about no one but herself,”

the Seeker priest finally said. “She'll not take you back if you return to Garlund so

soon, you know. She wants you to suffer. You're being made an example. She craves the

power, and you're a threat to her. None of the other villagers has the spunk to take her

on, is my guess.” “She's my mother,” Hederick whispered. “You've never met her. What would

you know?” The priest laughed. “I've met hundreds like your mother, Hederickmen as well as

women. I'm a priest. I run into all sorts of troubled souls who think they've reinvented

the gods.” He sighed, then failed to suppress a yawn. “I'll take you home in the morning,

Hederick. I believe I can make things right with your mother. Why not trust me, at least

for now? I'd hardly snatch you from a lynx's jaws to devour you myself, son.” Still

Hederick hesitated. “You'll take me back?” He imagined the villagers' faces when he strode

back into Garlund with this sword-wielding, towering heretic. “Tomorrow?” “If you wish.”

Hederick crouched to peer under the wide canopy. The rain streamed down his back. “Early?”

“At dawn, if you want.” A smile creased Tarscenian's face. “Lad, I'm bone-weary. I walked

many miles today. I did battle with a giant cat and, what's far more daunting, locked

horns with a stubborn twelve-year-old. The New Gods will watch over us tonight, Hederick.

I must sleep now, son, and I won't be able to if I must worry about you wandering off in

the rain. You'll be prey to every creature and lung ailment on the prairie.” He yawned

hugely. “Make your choice, lad. Truce?” “All right,” Hederick finally said. “But I'll

listen to nothing more about New Gods.” “For the night, anyway. Good enough.” Hederick

crawled back into the shelter, dribbling rainwater like a sodden kitten. Stripping off his

wet clothes, he accepted Tarscenian's spare shirt, so huge that the sleeves fell past his

fingertips. Dry again, Hederick curled up in his blanket. The priest, already snoring,

exuded heat like a hearth even though he'd relinquished both blankets. Hederick was asleep

in seconds.