Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (38 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

It’s lovely to see you, said Elie. But I have to go inside.

Maybe to my Kübelwagen, said Mueller. But not here.

Elie edged away. Mueller came closer and held her chin.

I have news for you, he said. And not the kind you get on Radio Free Europe.

I have all the news I need.

Not this news, said Mueller with reckless gaiety. Elfriede Heidegger has been poking around. She says her husband made a useless trip to Auschwitz and was left all by himself in the snow at an empty train station. Neither of them are pleased.

A useless trip, he continued. And now Goebbels has your name.

What other lies are you making up? said Elie.

He slapped her across the face. She felt it in her teeth.

I don’t have to make up lies, said Mueller, who was almost shouting. Goebbels knows you disobeyed an order, and he’s going to kill you. But I can hide you. I’m getting out of this war. You’d be surprised at the places I could take you.

I don’t want to be surprised.

Of course you do. You’ve been with that joke of a Nazi much too long.

He edged Elie into the tree. She felt sharp branches and needles piercing her back. He ripped open her blouse, and she felt warm air against her breasts. He shoved a hand against them. She held tight to the gun in her pocket.

There’s always been something between us, he said. I’ve been patient for over a year.

There’s never been anything between us.

Of course there has. Mueller jerked a sleeve of her blouse by the shoulders. Elie heard the hiss of ripping silk. She felt the pines turn to glass needles, the air a sweet poison. She imagined how he would tear off her clothes, and his ring would dig into her face, and his moustache would froth against her mouth—all while he forced himself into her. She pulled her revolver from her pocket and pointed its barrel against his ribs. Mueller took a step back.

So you have a gun, he said. Like everyone else in this fucking war.

Except I’m not afraid to use it, said Elie.

She fired a shot, just into the woods. And then another.

If you ever touch me again, I will kill you, she said.

I don’t think so. They’ll be after you soon enough. And that little boy with the

Echte Juden

? They know about him too. I made sure of that.

Echte Juden

? They know about him too. I made sure of that.

Elie fired another shot. Get out of here, she said.

Mueller pulled a bottle from his coat and took a long swig. He threw it to the ground and walked in the direction of the road. He hadn’t come from the forest but from his Kübelwagen. Elie heard it grumble into the night and walked over to Lars’s body. Without blood blooming on his chest, he might just be asleep. She pushed back his hair and stroked his forehead. She took a handkerchief and wiped blood from the corner of his mouth. She gathered pine boughs and covered his body. Then she picked up the bottle; it was French cognac with a small note around the neck—the same words on the order Lodenstein had seen:

Translators are traitors.

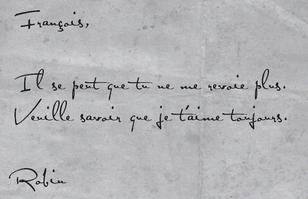

François,You may not see me again.Please know that I love you.Robin

Elie raced downstairs and looked through the Solomons’ window. Dimitri was sleeping near Talia and Mikhail, who were once again playing chess—so engrossed in the game they didn’t notice her. She went upstairs where Lodenstein was putting a note into the trunk.

Do you ever stop finding things? she said.

They keep washing up, said Lodenstein.

Like stuff from the sea, said Elie.

Like stuff from the war, he said.

Elie took off her ripped clothes and got into bed. Lodenstein got into bed with her.

You can’t go out so late, he said. You know they blew up the gas chambers.

Elie hesitated. Then she said:

Mueller was in the forest. He’s a deserter now.

I’m not surprised, said Lodenstein. He reached for the last of the brandy. We should drink to never having to worry about him again.

Gerhardt, she said. I have terrible news. Mueller shot Lars. He killed him.

I don’t understand.

I wouldn’t either if I hadn’t seen it. Just now. In the forest.

Lodenstein began to cry, and Elie rocked him, feeling the bruise of pine needles at her back, wishing she never had to tell him such news.

Look at what I’ve brought to this place, she said.

Lodenstein forced himself to stop crying. You only bring good things, he said.

I don’t, said Elie. Not at all.

Lodenstein lit a lantern and put his arms around her. Elie watched the soft circle of light on the ceiling.

We’re still in this room, he said. And we’re still together. Mueller’s not going to come back. He just wanted to scare you.

But there are things to be scared of, said Elie. Mueller told the Reich about Dimitri. He says the Heideggers are bothering Goebbels again. They told him my name.

He’s bluffing.

No, said Elie, he isn’t. He’d left the Compound by the time Stumpf went to deliver the glasses to Heidegger. He doesn’t know Stumpf told them my name.

Elie, listen. We’ve been through the worst of it. We’ll make it through now.

They could still come after me.

There’s always the room in the tunnel.

Suppose the Gestapo’s there?

No one’s going to be there. We’ve come to the end of this war.

A bedtime story

, Elie thought.

Something I’d tell Dimitri

. Still, she leaned closer to Lodenstein, trying to ignore the stinging in her back and an image of Lars’s body alone in the forest. Lodenstein was real, durable, alive. And the room almost felt safe. He turned off the lantern, and they lay beneath the grey silk comforter. It was tattered. Elie touched one of the holes.

, Elie thought.

Something I’d tell Dimitri

. Still, she leaned closer to Lodenstein, trying to ignore the stinging in her back and an image of Lars’s body alone in the forest. Lodenstein was real, durable, alive. And the room almost felt safe. He turned off the lantern, and they lay beneath the grey silk comforter. It was tattered. Elie touched one of the holes.

We ought to get another one, she said. This is careworn.

Careworn

, said Lodenstein, just before he fell asleep.

, said Lodenstein, just before he fell asleep.

Elie lay next to him, trying to retrieve the comforting sense of dark. But it dissolved into images of Lars’s body and the sensation of Mueller’s hands ripping open her blouse.

The night has been broken for me

, she thought, not knowing if she were remembering something she’d heard or if it were something she’d just thought of.

, she thought, not knowing if she were remembering something she’d heard or if it were something she’d just thought of.

But no matter where it came from, the thought the

night has been broken for me

acted on her strangely. She couldn’t lie still or enjoy the quiet comfort of Lodenstein’s body. Nor could she trust what he’d told her. She dressed in her ripped clothes, covered them with her coat, and went downstairs. The mineshaft opened. She saw Asher coming from the main room.

night has been broken for me

acted on her strangely. She couldn’t lie still or enjoy the quiet comfort of Lodenstein’s body. Nor could she trust what he’d told her. She dressed in her ripped clothes, covered them with her coat, and went downstairs. The mineshaft opened. She saw Asher coming from the main room.

Stupid of me, he said when he saw her. What does it matter if I stand next to them?

Elie said she didn’t know what he meant, and he told her he was so worried about Daniel getting Maria pregnant he sometimes stood next to their desks—as if his presence were a kind of birth control. He said it was strange and aberrant, listening to his own son making love.

As strange as anything I’ve ever done, he said.

Don’t worry, said Elie. Maria has a lot of French letters.

That’s good, said Asher. They’re the only letters here worth answering.

Elie laughed and was surprised that she could. Asher sat next to her on the bench. She touched the blue numbers on his arm.

Those match your eyes, she said to him again.

That’s good, he said, because I’m going to have these numbers for a long time.

The phrase

the night has been broken for me

came back to her. She began to fuss with her blouse so Asher couldn’t see it was torn.

the night has been broken for me

came back to her. She began to fuss with her blouse so Asher couldn’t see it was torn.

What is it? he said.

Nothing, said Elie. Just…how do you explain that the night has been broken?

No one has to, said Asher.

Elie nodded.

She suddenly remembered getting out early from a lecture and seeing Asher and Gabriela walking in a little park in the rain. They were bathed in mist, and Elie saw them the way one sees distant figures about to disappear. She’d raced to catch up, and all three of them had walked into the mist together. She hadn’t remembered this moment in years. She loved and ached at the sight of the two of them. An ocean of fear swelled and subsided inside her.

What did you really see in Auschwitz? she asked.

Asher took a deep breath.

Everything, he answered.

Elie had an odd sensation that she and Asher shared a private universe—different from the one she shared with Lodenstein. This world was from long before the war—a world of unveilings, revelations, disclosures. She and Lodenstein were partners in a mission. They shared terror about the Compound and hope for their future. She looked at the mineshaft and a sliver of the kitchen where Lars once peeled apples in perfect spirals.

Can I talk to you alone? she said.

Asher nodded, and they walked down the hall.

Once more Elie was reminded of Asher’s office in Freiburg. She saw papers with phrases in

Dreamatoria

, as well as books. There were also typewriters in every stage of reconstruction and disarray and a blue and white coffee mug on a book. Inside the storage room, Asher lit the Tiffany lamp and handed Elie a glass of wine.

Dreamatoria

, as well as books. There were also typewriters in every stage of reconstruction and disarray and a blue and white coffee mug on a book. Inside the storage room, Asher lit the Tiffany lamp and handed Elie a glass of wine.

But Elie pushed the wineglass away and told Asher that things were in a shambles: Mueller had just killed Lars. The Heideggers gave Goebbels her name. And Goebbels knew about Dimitri. Her voice shook. She was close to tears.

This place isn’t safe, she said. And you and Daniel and Dimitri aren’t safe. You have to find a way to take them to Denmark.

We’d all be shot our first night in the forest.

Asher, you don’t understand. You’re in too much danger if you stay. Elie began to cry. She couldn’t stop and put her head in a pillow.

Elie, said Asher.

What? said Elie.

This, he said. And he put his arms around her.

Elie felt an arc of warmth through her body. Asher stroked her hair and held her as if he knew everything—the pine needles at her back, the sound of gunshots, the hiss of ripping silk. And how, in spite of hundreds of forays, she could never find the one person she was looking for.

When she had stopped crying, Elie stood up and looked at the stacks of books, the notes for

Dreamatoria

, the cartridges, keys, spools—all manner of metallic shapes.

Dreamatoria

, the cartridges, keys, spools—all manner of metallic shapes.

Thank you, she said.

Other books

Strange Neighbors by Ashlyn Chase

Who Do I Talk To? by Neta Jackson

Traitor and the Tunnel by Y. S. Lee

Purebred by Georgia Fox

The Rabbit Who Wants To Fall Asleep: A New Way Of Getting Children To Sleep by Carl-Johan Forssén Ehrlin

The Rightful Heir by Angel Moore

Curtain Up by Lisa Fiedler

Cronkite by Douglas Brinkley

Luminous by Egan, Greg

Cherringham--The Last Puzzle by Neil Richards