Helix and the Arrival (2 page)

Read Helix and the Arrival Online

Authors: Damean Posner

The cave lion, I think, is smiling. âThat'll teach you to aim your spear at my baby,' she's thinking. And in a few powerful bounds she's gone, back up to the mountain to collect her cub and probably to look for a new cave.

Meanwhile, to make matters worse, Sherwin loses his footing and goes tumbling down the rock face making

ooh

,

argh

,

ouch

,

ptumf

noises all the way until he falls at my feet.

âYour. Fault,' he groans, looking up.

âSorry,' I shrug.

âMauled ⦠I've been mauled!' he cries, reaching for his back.

There are four scratch marks that have sliced through Sherwin's skin. Luckily for him, his hairiness has acted as fur-shield and stopped the claws from cutting too deeply.

âAre you okay, son?' says Dad, who has only just got to his feet and recovered from his crash landing.

Sherwin groans and stands in pain. His face is sour, as if he's just been made to eat a handful of unripe hill berries. He looks at Dad and says, pointing to me, âHe is a disgrace to our family.'

âWhat do you mean?' I ask. âI was the one who spotted the cave lion. If it weren't for me, we'd be cave lion dinner right now.'

âYou made me miss in the first place. I had the beast in my sights,' says Sherwin.

âYou mean the cub,' I say. âThe defenceless cub.'

Dad steps between us. âLet's calm things down, boys. All in a day's hunt. The experience will do you good â help you to prepare for your Arrival, Helix.'

âNo it won't,' says Sherwin. âHe's a coward, not a hunter. All he's good at doing is running.'

âShut up. Just shut up,' is all I can say, before sprinting away to be on my own.

Turning thirteen is when caveboys miraculously change from skinny, hairless, squeaky-voiced cowards (more of a description of me than your average caveboy), to thick-browed, hair-covered, deep-grunting cavemen.

Sorry, but it's not going to happen.

There are two parts to becoming a caveman: the spoken test and the hunt. Together they form the Arrival.

Speel the Storykeeper is in charge of the test, which goes a bit like this:

Question: Where did mountain folk come from?

Answer: They came from Fleg and Fler, who were the first caveman and cavewoman on the mountain and who founded Rockfall.

Question: What are the names of all the Korgs (Korg is the title we give to the ruler of the mountain) dating back to Korg the Originator, the first ever Korg?

Answer: Korg the â¦

yawn

. (Note: this is when you basically name every single Korg that ever lived. There are as many Korgs as rocks on the mountain, so quite a few to remember.)

Question: Where did river people come from? (The river people are our enemy.)

Answer: They grew out of the mud in the lowlands. (Extra marks if you say it with a grimace.)

And on it goes â¦

To be honest, Speel's Arrival test is easy. The answers have been drummed into me since I was a cavekid. My only problem, though, is believing the answers.

Take Fleg and Fler and the forbidden rock, for example. It's an interesting story â especially the part where a talking claw-gripped fork-tongued vulture convinces Fleg to crack the forbidden rock on his forehead (at which he succeeds) to impress Fler. But why would someone want to crack a rock over their head? I don't understand and I want to read the sacred tablet of Fleg and Fler for myself, instead of having Speel hold it close to his chest and read each word as if it's a story that only he can tell.

In the past, I've asked Speel if I could see the sacred tablet that tells the story of Fleg and Fler.

âSacred tablets are not for your eyes,' is the answer I got.

Speaking of eyes, Speel has only one of them. A tusk boar, so the story goes, gored his other eye when he was younger. As a result, he wears a patch over the missing eye, which is probably a good thing because no one wants to see an eye socket missing an eyeball.

As Storykeeper, Speel controls all of the knowledge contained in the stone tablets. His word is the final word.

âDo the tablets say what Fleg and Fler looked like?' I've asked him before, trying to find out something ⦠anything.

âOf course â in great detail,' he had replied. Then he'd gone on to describe a hairy, thick-browed guy named Fleg and an almost equally hairy girl named Fler.

Enlightening. That description could match almost anyone in Rockfall.

Then there's the story of the river people from the lowlands, who are meant to be bad in every way. With Fleg and Fler, there's no way of me knowing whether their story is true, but with the river people I should be able to find out for myself, right?

Wrong. Making contact with the river people is forbidden. The river, you see, separates mountain folk from river folk. And no one is allowed to cross the river. As much as I'd like to, I can't just wander into the lowlands and say, âHello, river person. Do you mind telling me if it's true that you grew from the mud, live a sad and worthless life, and eat food that sprouts from the ground?' Instead, I have to rely on Speel's version, the only version there is of the river people's story.

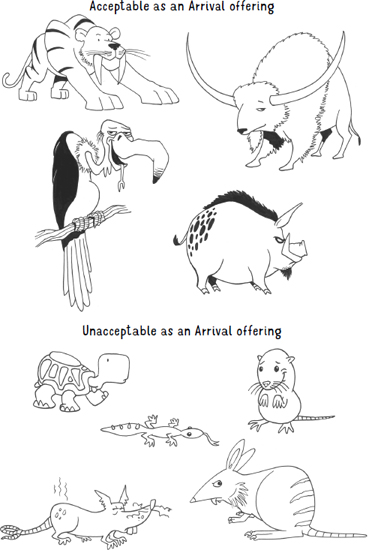

Like I said, though, the test is the easy part. It's the hunt that's impossible (well, for me, at least). It's like a huge boulder blocking my path and stopping me from passing my Arrival. For the hunt, you're supposed to disappear into the woods and return with something big, dangerous or rare:

âBig' means weighing more than you or, in the case of something like a poison-fanged rock monitor, being longer than you (even though I'm light and short, if I saw a creature heavier or longer than me, I think I'd practise my fastest running).

âBig' means weighing more than you or, in the case of something like a poison-fanged rock monitor, being longer than you (even though I'm light and short, if I saw a creature heavier or longer than me, I think I'd practise my fastest running).

âDangerous' means that the animal has teeth, horns, claws or venom capable of killing (anything in this category can go free as far as I'm concerned).

âDangerous' means that the animal has teeth, horns, claws or venom capable of killing (anything in this category can go free as far as I'm concerned).

âRare' pretty much means a sacred bison. If you kill a sacred bison, you automatically pass and probably get to become the next Korg.

âRare' pretty much means a sacred bison. If you kill a sacred bison, you automatically pass and probably get to become the next Korg.

I've never spent a night in the woods alone. I've never even been in the woods alone. The woods are dark even during the day. There are strange growls and hoots and the wind howls through the treetops like a crazed vulture.

What's more, during your Arrival you have to make your own fire in the woods

and

there are no caves. What if it rains? What happens to the fire then? Yep â there's no way I'm spending a night alone in the woods.

And there lies my problem. This whole hunting business just isn't for me. It wouldn't be so bad if I'd

been born Korg or Speel. Then I could sit back in front of a fire all day long, look wise and give out advice to other mountain folk.

The reality is, though, I'm no one special. Just Helix, son of Jerg (who's also a coward but manages to cover it up really well). If I fail the Arrival, my family will be disgraced, and it's likely I'll be banished to the Dark Side of the mountain.

So, as of today, because of who I am, I have no hope of passing my Arrival. My story might as well end here, but I'll keep telling it anyway.

It's morning. I hear Mum near the front of the cave, bringing last night's hot coals back to life. She's preparing meat-on-a-stick for breakfast â the usual. It's whatever Dad and Sherwin caught the day before. Probably cave rodents or mountain voles. Mum cooks it until it's as black as the charcoal in the fire and it tastes much the same.

âTime to get up,' says Mum.

Dad sits up beside me and yawns. âAnother day, another opportunity, boys. Come on, time for the men of this cave to get up.'

Sherwin moans and rolls over away from Dad. It's quite possible that Sherwin is the laziest caveman on the mountain. I once saw him watch a beetle crawl up his arm, onto his shoulder, along his cheek and into his nose. Who knows where it is now? Probably

living off the snot boulders trapped in his nose hair. And all this because he was too lazy to swat it.

The four of us sleep shoulder to shoulder â Dad and Sherwin are normally on the outside, while Mum and I are in the middle. Because of all the snoring, I've considered sleeping with my head up the other end, but Sherwin's putrid foot odour is much worse than his snoring and bad breath.

Each of us has a sleeping skin that, in winter, we pull up above our eyes. There's also a bigger, separate skin on the cave floor that we sleep on top of. It's made up of various small creatures that Dad has hunted over the years. For all I know, I could be sleeping above fifty generations' worth of rock gerbil.

Dad doesn't care that his two sons are acting like mountain sloths. âIt's time for at least one of the men in this family to seize the day,' he says, standing up and stretching his skinny arms above his head.

I sit up, yawn and rub my eyes. Sherwin isn't moving. He's pretending to be asleep.

Most cavemen are married by the time they turn fifteen or sixteen. Sherwin, at seventeen, is leaving it late. All of his childhood friends have wives. He's the odd one out, still living at home with his parents and annoying younger brother (that's me).

The caveman timeline goes something like this:

0â8: cavekid. The cavekid years are all about freedom. You get to run, climb, collect rocks and play games like bite and squeak with your best friend (first one to squeak loses).

0â8: cavekid. The cavekid years are all about freedom. You get to run, climb, collect rocks and play games like bite and squeak with your best friend (first one to squeak loses).

8â12: caveboy. Although you're not a caveman yet, life becomes a bit more serious. You're expected to be able to throw a spear, wield a club and prepare for your Arrival.

8â12: caveboy. Although you're not a caveman yet, life becomes a bit more serious. You're expected to be able to throw a spear, wield a club and prepare for your Arrival.

13: become a caveman. This is when a big, dark cloud called the Arrival enters your life, and you go from being a carefree caveboy to an I'm-so-tough-you-could-crack-a-rock-over-my-eyeball caveman.

13: become a caveman. This is when a big, dark cloud called the Arrival enters your life, and you go from being a carefree caveboy to an I'm-so-tough-you-could-crack-a-rock-over-my-eyeball caveman.

13â18: prime caveman. In theory, these are the best years of a caveman's life, assuming you don't get eaten by something bigger than you or banished to the Dark Side.

13â18: prime caveman. In theory, these are the best years of a caveman's life, assuming you don't get eaten by something bigger than you or banished to the Dark Side.

18â35: middle-aged caveman. This is the time when a caveman reaches full maturity. Hopefully he has a few sons by now who can take over the hunting duties and listen to stories about the time he almost captured a sacred bison.

18â35: middle-aged caveman. This is the time when a caveman reaches full maturity. Hopefully he has a few sons by now who can take over the hunting duties and listen to stories about the time he almost captured a sacred bison.

35â50: old-aged caveman. Time to slow down and look back at your long life. A caveman's life expectancy is about ⦠NOW!

35â50: old-aged caveman. Time to slow down and look back at your long life. A caveman's life expectancy is about ⦠NOW!

50+: ancient caveman. Anyone who reaches fifty is seen as having special powers and is presented with a special commemorative tablet from Korg.

50+: ancient caveman. Anyone who reaches fifty is seen as having special powers and is presented with a special commemorative tablet from Korg.

I stand up slowly and take a few sluggish steps towards the front of the cave where Mum is waiting for our breakfast to turn black. She's sitting cross-legged on a skin, detangling her hair with a small comb made from animal bone.

I sit down beside her and she smiles at me with her kind but strong eyes. Dad is sitting across the fire from me, warming his hands from the morning cold.

âA Gathering has been called for this morning,' he says, rubbing his hands together a bit faster.

Usually, nothing very exciting happens at Gatherings. It'll probably be the usual announcements of births, deaths and marriages.

âWhat will you do after the Gathering, Helix?' asks Mum.

âI'm meeting Ug.'

âThat's nice.'

âHe's going to show me how to wield a heavy club,' I say, because I know this will please her.

Her eyes light up. âA heavy club! Did you hear that, Jerg? Our Helix is growing up!'

Dad is cleaning his teeth with a wooden pick. âHeavy club? Good weapon, son.' His voice comes out muffled.

I don't think Dad has ever hunted with a heavy club. Like me, I doubt if he could even lift one above his head.

âYou with a heavy club â I'd like to see that,' comes Sherwin's voice, from the back of the cave.

âLook who's awake,' says Dad. âThinking of joining us?'

âNo, I need my rest.'

Sherwin became a caveman the day he turned thirteen. For the hunting part of his Arrival, he caught a poison-fanged rock monitor. It was the longest one anyone had caught that season and it fed our family for many days afterwards. Since then, his favourite pastime has been sleeping, and he hasn't done a lot of hunting.

âWhat about your Arrival test?' says Mum. âHave you been studying?'

âI know what it is we're meant to know,' I say. âI've been listening to Speel read the tablets for years â it's not that hard to remember. I even read a few tablets myself, when he wasn't watching.'

âHow about our son?' says Dad to Mum. âThe boy can read word signs. Never been taught, but he can still read them.' Dad shakes his head in amazement.

âHow do you do it, Helix?' asks Mum.

It's a good question. How

do

I do it? âThey just make sense to me,' I say.

Most tablets say pretty much the same thing, anyway. First of all, there's the begetting â everyone seems to beget everyone else. Then there is talk of the heavens, which is almost always followed by the word âglorious'. It seems that everything cave people have

ever done has been glorious, especially when compared to the river people who, if you believe Speel, have been swimming in mud since the day they were created.

Sherwin has decided it's time to get up. He shuffles over to the fire, deliberately swiping my head with his elbow as he sits down beside me.

âOuch!' I say. âThat hurt.'

âSorry, little bro. Was an accident.'

âSure it was,' I say.

âBoys,' says Mum, in her warning tone. Beside her is the whacking stick, though it could almost be described as a club. Mum's used it to threaten us with discipline for as long as I can remember. One good shake of the whacking stick is normally enough to get us to stop doing whatever it is we're doing. Even on its own and not in Mum's hand, it looks threatening.