Henry IV (41 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

56

PROME

, viii.122–5.

57

A petition in French from the archbishops and bishops addressed to parliament and preserved in Thomas Hoccleve's formulary reminded the king that ‘in other realms subject to the Christian religion when any persons are condemned by the church for the crime of heresy they are promptly handed over to secular judgment to be put to death and their temporal goods confiscated’, and went on to ask for help from the ‘secular arm’ in the campaign to eliminate heretics ‘so that those who are unwilling to be corrected and amended by spiritual discipline should be punished by temporal punishment’; this ‘help’ was to be ‘by way of a statute’ (H. G. Richardson and G. Sayles, ‘Parliamentary Documents from Formularies’,

BIHR

(1934), 152–4; BL Add. MS 24.062, fo. 189v). This does not quite amount to requesting the introduction of the death penalty for heresy in England, although there is no doubting the implication. However, the fact that the archbishops should ask for this power to be set down in a statute does not mean that they were asking for a new type of punishment for heresy to be introduced (as noted above, heretics had been burned in England before), but rather that this was something which they felt should be confirmed by being enshrined in statute form. However the petition does not seem to have been actually submitted to parliament, for it is not recorded on the parliament roll. Richardson and Sayles dated this to January 1397, which has generally been accepted, but the evidence for this is inferential and it seems just as likely that it was intended for the parliament of January 1401, as a supplementary petition to the clergy's petition on Lollard schools and conventicles which, as frequently noted, was in Latin, which was very unusual for parliamentary petitions. If so, it was presumably in response to this that the final paragraph of the king's reply detailing the secular punishments for heretics was added; this was incorporated in the statute, although the petition itself had said nothing about forms of secular punishment. It is worth noting Usk's comment (p. 8) that ‘my lord of Canterbury, forewarned of [the Lollards'] evil schemes, had prepared suitable counter-measures’.

58

PROME

, viii.121.

59

SAC II

, 308;

PROME

, viii.122–5, 139.

60

CPR 1399–1401

, 190; McNiven,

Heresy and Politics

, 82. McHardy, ‘De Heretico Comburendo’, 118. See also

CCR 1399–1402

, 185, an order from the king to the sheriffs to clamp down on unlicensed preaching dated May 1400.

61

Records of Convocation IV

, 233–6;

PROME

, viii.121;

Usk

, 126–7.

62

Usk

, 126–7.

63

PROME

, viii.104;

Original Letters

, i.8–9.

64

CE

, 388.

65

Davies,

Revolt

, 5–93.

66

Brecon had been a Bohun, not a Lancaster, lordship.

67

RHKA

, 217–23.

68

PROME

, viii.136, 140, 144–5.

69

CPR 1399–1401

, 469–70;

Foedera

, viii.184. Davies,

Revolt

, 287–8, and

PROME

, viii.96–7, argue that Henry tried to moderate the commons' demands, but the council ordinances had the opposite effect.

70

PROME

, viii.104–5, 144–5.

71

For the anti-Welsh legislation and its context, see Davies,

Revolt

, 284–92.

72

CPR 1399–1401

, 451;

Foedera

, viii.181–2.

Chapter 13

THE PERCY ASCENDANCY (1401–1402)

It was the combination of rebellion in Wales and intensified hostility on the Anglo-Scottish border during the early years of Henry IV's reign that led to the augmentation of the power of the Percys. No family apart from the king's had profited more from the deposition of Richard II. Before 1399 was out, Northumberland had been made constable of England for life and warden of the West March for ten years, granted the Isle of Man, and put at the head of a consortium which farmed the Mortimer inheritance during the young earl's minority. His son Hotspur became warden of the East March, also for ten years, sheriff of Northumberland, justiciar of Chester and North Wales, and sheriff of Flintshire; he was granted the lordship of Anglesey and custody of the Mortimer lordship of Denbigh. Father and son thus secured a virtual monopoly of civil and military power on the Scottish marches and in North Wales. Meanwhile Thomas Percy, the earl's brother, was one of only two men permitted to keep the title to which he had been promoted in 1397 (earl of Worcester); became admiral of England for life; and was appointed to head the negotiations with the French over Queen Isabella's return.

1

This cascade of offices and favours was not simply reward for the Percys' help in 1399, crucial as that was. It also recognized the long and lauded careers of all three of them as soldiers, diplomats, Knights of the Garter and supporters and kinsmen of the House of Lancaster.

2

Probably by design, the roles adopted by the Percys during the early years of Henry's reign were demarcated. Hotspur, first and foremost a

soldier, took charge of the defence of the northern border and the pacification of Ricardian Cheshire, and was rarely in London. Worcester, except when abroad on embassies or supervising naval operations, remained with the king. Northumberland stayed for the most part at Westminster, the leading lay magnate on the council, involved in planning of all kinds, although he did not entirely delegate his responsibilities in the north to his son.

3

The parliament of 1401 and its aftermath saw a further increase in their responsibilities.

4

In March, Worcester became steward of the royal household, and in October he was appointed to be Prince Henry's governor; in the same month, the farm of the Mortimer inheritance was granted to Northumberland alone. However, with the seizure of Conway by the Tudor brothers, it was the brilliant and unpredictable Hotspur who was catapulted to the forefront of the nation's affairs, for it was to him that the king entrusted its recapture.

Gwilym Tudor was the leader of the forty or so men who infiltrated Conway castle on 1 April 1401, choosing a moment when the captain was away and all bar five defenders were attending a Good Friday service in the town.

5

Hotspur swiftly invested the castle, but it took four weeks for Prince Henry to come to his help.

6

By this time negotiations were under way for it to be surrendered, as eventually happened in late May: in return for vacating the castle, the rebel leaders received pardons for everything they had done hitherto (including their devastation of Conway town), but were obliged to hand over nine of their party to the prince, who promptly executed them with predictable savagery – ‘a most shameful thing for [Gwilym and Rhys] to have done’, in Usk's view, ‘and an act of treachery against their fellows’.

7

Nevertheless, the psychological boost of the Conway escapade – an exploit which, had it been performed by Englishmen in France, would have found its way into annals of chivalric heroism – was widely felt. Conway castle was reckoned to be almost impregnable. It was where Richard had taken refuge

in August 1399, just a year after retaining Rhys and Gwilym.

8

If the brothers' primary aim in capturing it was to secure pardons, they must also have enjoyed cocking a snook at the man who had deposed their former patron. Glyn Dwr himself played no part in their exploit, and they sought no pardon for him; indeed it may be that at this stage they saw themselves more as rivals to Owain for leadership of the Welsh cause than as his adherents. Yet the consequence of their audacity, intentional or otherwise, was to galvanize Owain into action once more, perhaps in the hope that he too might secure a pardon. This was precisely what the king had feared. While Hotspur questioned the wisdom of the anti-Welsh ordinances and grew testy about Henry's failure to send him sufficient funds, Henry's main concern was the precedent set by offering such lenient terms to rebels.

9

Not the least of the brothers' achievements was to sow seeds of mistrust within English ranks.

Summer 1401 saw the revolt spread into Central Wales and even to Carmarthenshire and Brecon.

10

By early June the king was sufficiently worried to advance as far as Worcester, planning to lead an army into Wales himself, although on this occasion, hearing news of some minor English successes and believing the remaining rebels to be ‘only of little reputation’, he decided to turn back.

11

By the autumn, however, the situation had worsened, with Harlech under siege and Aberystwyth threatened, and at the beginning of October Henry and the prince led a sizeable army into Wales, arriving before Caernarfon on 8 October and then moving south to vent their fury on the Cistercian monks of Strata Florida, who were believed to be in league with the rebels.

12

Owain could not be found, however, despite spies and messengers being sent out to hunt him down.

13

When Llywellyn ap Gruffudd Fychan of Caio, who had offered to lead the king to the Welsh leader but knowingly misled him, was interrogated by

Henry as to why he had done so, he replied that he would prefer to lose his head rather than betray Glyn Dŵr's counsel. His wish was granted, but his example applauded. ‘We English could learn a lesson from this’, wrote the Evesham chronicler, ‘to keep our counsels and secrets faithfully between ourselves even unto death’.

14

Yet Owain had not gone far, and as soon as Henry returned to Shrewsbury on 15 October, after barely two weeks in Wales, he emerged from hiding, sacked Welshpool, then marched his men to Caernarfon where, on 2 November, he raised his princely standard, a golden dragon on a white field, although on this occasion he was beaten off by a sortie from the garrison.

15

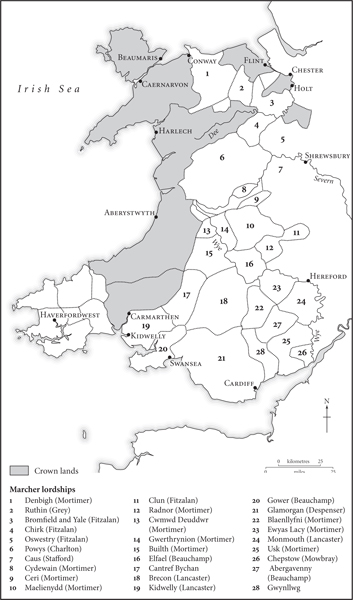

Map 4

Wales and the Glyn Dŵr Revolt

Shortly before this, perhaps while the king was still in Wales, Glyn Dŵr let it be known through the Percys and Edmund Mortimer (Hotspur's brother-in-law) that like the Tudor brothers he would be prepared to submit to the king in return for a promise to spare his life, but when this was put to the council at Westminster in November 1401 it declined to accept his plea.

16

With hindsight, it is easy to recognize that passing up this opportunity came back to haunt the English, but there was nothing straightforward about the decision. The revolt was still some way short of a national uprising, royal agents were busily accepting submissions and obligations from former rebels, a formidable series of military commands had just been set up throughout Wales, and Henry probably reckoned that, having allowed thirty-five rebels to walk out of Conway unscathed, any further sign of weakness would simply provide encouragement to others.

17

Nor was it clear that Owain's surrender would bring the revolt to an end; the pardon of the Tudor brothers had not done so. Owain's offer of submission tells us as much about his own problems as about the English crown's. His leadership of the revolt was not yet secure, and for the moment his defiance seemed to have been checked.

That soon changed, however, as 1402 began with a raid on Ruthin, the lordship of Owain's old enemy Reginald Grey, enabling the rebels to replenish their stock of cattle.

18

In April, Grey learned that the Welsh leader was once again in the vicinity of Ruthin: setting off in pursuit with a small force, he ventured into unfamiliar territory, only to find himself

ambushed and led away to Snowdonia ‘bound tightly with thongs’.

19

Then, on 22 June, at the battle of Bryn Glas or Pilleth, just south of Knighton (Powys), Owain secured an equally notable and ultimately more significant triumph when his forces overcame a levy from Herefordshire led by Edmund Mortimer, capturing Mortimer himself and killing several hundred of his men. Stories of the mutilation of the corpses by Welsh women aroused indignation in England, but more corrosive of English morale were the rumours of treachery among Edmund's followers and even of collusion in his own capture by Mortimer himself, rumours which the king and his advisers at Westminster believed. From this time onwards, wrote the Evesham chronicler, ‘Owain's cause began to flourish greatly, and ours to fail’.

20

Prevented by the king from ransoming himself – a source of real controversy, especially since Reginald Grey ransomed himself for £6,666 and was free by the end of the year – Edmund married Glyn Dŵr's daughter Catherine on 30 November 1402 and two weeks later wrote to his vassals announcing that henceforth he would strive to vindicate his father-in-law's rights in Wales.

21