Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes (23 page)

Read Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

We proposed the theory of punctuated equilibrium largely to provide a different explanation for pervasive trends in the fossil record. Trends, we argued, cannot be attributed to gradual transformation within lineages, but must arise from the differential success of certain kinds of species. A trend, we argued, is more like climbing a flight of stairs (punctuations and stasis) than rolling up an inclined plane.

Since we proposed punctuated equilibria to explain trends, it is infuriating to be quoted again and again by creationists—whether through design or stupidity, I do not know—as admitting that the fossil record includes no transitional forms. Transitional forms are generally lacking at the species level, but they are abundant between larger groups. Yet a pamphlet entitled “Harvard Scientists Agree Evolution Is a Hoax” states: “The facts of punctuated equilibrium which Gould and Eldredge…are forcing Darwinists to swallow fit the picture that Bryan insisted on, and which God has revealed to us in the Bible.”

Continuing the distortion, several creationists have equated the theory of punctuated equilibrium with a caricature of the beliefs of Richard Goldschmidt, a great early geneticist. Goldschmidt argued, in a famous book published in 1940, that new groups can arise all at once through major mutations. He referred to these suddenly transformed creatures as “hopeful monsters.” (I am attracted to some aspects of the non-caricatured version, but Goldschmidt’s theory still has nothing to do with punctuated equilibrium—see essays in section 3 and my explicit essay on Goldschmidt in

The Panda’s Thumb

.) Creationist Luther Sunderland talks of the “punctuated equilibrium hopeful monster theory” and tells his hopeful readers that “it amounts to tacit admission that anti-evolutionists are correct in asserting there is no fossil evidence supporting the theory that all life is connected to a common ancestor.” Duane Gish writes, “According to Goldschmidt, and now apparently according to Gould, a reptile laid an egg from which the first bird, feathers and all, was produced.” Any evolutionist who believed such nonsense would rightly be laughed off the intellectual stage; yet the only theory that could ever envision such a scenario for the origin of birds is creationism—with God acting in the egg.

I am both angry at and amused by the creationists; but mostly I am deeply sad. Sad for many reasons. Sad because so many people who respond to creationist appeals are troubled for the right reason, but venting their anger at the wrong target. It is true that scientists have often been dogmatic and elitist. It is true that we have often allowed the white-coated, advertising image to represent us—“Scientists say that Brand X cures bunions ten times faster than…” We have not fought it adequately because we derive benefits from appearing as a new priesthood. It is also true that faceless and bureaucratic state power intrudes more and more into our lives and removes choices that should belong to individuals and communities. I can understand that school curricula, imposed from above and without local input, might be seen as one more insult on all these grounds. But the culprit is not, and cannot be, evolution or any other fact of the natural world. Identify and fight your legitimate enemies by all means, but we are not among them.

I am sad because the practical result of this brouhaha will not be expanded coverage to include creationism (that would also make me sad), but the reduction or excision of evolution from high school curricula. Evolution is one of the half dozen “great ideas” developed by science. It speaks to the profound issues of genealogy that fascinate all of us—the “roots” phenomenon writ large. Where did we come from? Where did life arise? How did it develop? How are organisms related? It forces us to think, ponder, and wonder. Shall we deprive millions of this knowledge and once again teach biology as a set of dull and unconnected facts, without the thread that weaves diverse material into a supple unity?

But most of all I am saddened by a trend I am just beginning to discern among my colleagues. I sense that some now wish to mute the healthy debate about theory that has brought new life to evolutionary biology. It provides grist for creationist mills, they say, even if only by distortion. Perhaps we should lie low and rally round the flag of strict Darwinism, at least for the moment—a kind of old-time religion on our part.

But we should borrow another metaphor and recognize that we too have to tread a straight and narrow path, surrounded by roads to perdition. For if we ever begin to suppress our search to understand nature, to quench our own intellectual excitement in a misguided effort to present a united front where it does not and should not exist, then we are truly lost.

IN HIS SUMMATION

to the court, Clarence Darrow talked for three full days to save the lives of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb. Guilty they clearly were, of perhaps the most brutal and senseless murder of the 1920s. By arguing that they were victims of their upbringing, Darrow sought only to mitigate their personal responsibility and substitute a lifetime in jail for the noose. He won, as he usually did.

John Thomas Scopes, defendant in Darrow’s next famous case, recalled his attorney’s theory of human behavior in the opening lines of an autobiography published long after the famous “monkey trial” (see bibliography): “Clarence Darrow spent his life arguing teaching, really—that a man is the sum of his heredity and his environment.” The world may seem capricious, but events have their reasons, however complex. These reasons conspire to drive events forward; Leopold and Loeb were not free agents when they bludgeoned Bobby Franks and stuffed his body into a culvert, all to test the idea that a perfect crime might be committed by men of sufficient intelligence.

We wish to find reasons for the manifest senselessness that surrounds us. But deterministic theories, like Darrow’s, leave out the genuine randomness of our world, a chanciness that gives meaning to the old concept of human free will. Many events, although they move forward with accelerating inevitability after their inception, begin as a concatenation of staggering improbabilities. And so we all began, as one sperm among billions vying for entry; a microsecond later, I might have been the Stephanie my mother wanted.

The Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee, occurred as the outcome of accumulated improbability. The Butler Act, passed by the Tennessee legislature and signed by Gov. Austin Peay on March 21, 1925, declared it “unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the state—which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” The bill could have been beaten with little trouble had the opposition bothered to organize and lobby (as they had the previous year in Kentucky, when a similar bill in similar circumstances went down to easy defeat). The senate passed it with no enthusiasm, assuming a gubernatorial veto. One member said of Mr. Butler: “The gentleman from Macon wanted a bill passed; he had not had much during the session and this did not amount to a row of pins; let him have it.” But Peay, admitting the bill’s absurdity and protesting that the legislature should have saved him from embarrassment by defeating it, signed the act as an innocuous statement of Christian principles: “After a careful examination,” wrote Peay, “I can find nothing of consequence in the books now being taught in our schools with which this bill will interfere in the slightest manner. Therefore it will not put our teachers in any jeopardy. Probably the law will never be applied…. Nobody believes that it is going to be an active statute.” (See Ray Ginger’s

Six Days or Forever?

for a fine account of the legislative debate.)

If the bill itself was improbable, Scopes’s test of it was even more unlikely. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) offered to supply council and provide legal costs for any teacher willing to challenge the act by courting an arrest for teaching evolution. The test was set for the favorable urban setting of Chattanooga, but plans fell through. Scopes didn’t even teach biology in the small, inappropriate, fundamentalist town of Dayton, located forty miles north of Chattanooga. He had been hired as an athletic coach and physics teacher but had substituted in biology when the regular instructor (and principal of the school) fell ill. He had not actively taught evolution at all, but merely assigned the offending textbook pages as part of a review for an exam. When some town boosters decided that a test of the Butler Act might put Dayton on the map—none showed much interest in the intellectual issues—Scopes was available only by another quirk of fate. (They would not have asked the principal, an older, conservative family man, but they suspected that Scopes, a bachelor and free thinker, might go along.) The school year was over, and Scopes had intended to depart immediately for a summer with his family. But he stayed on because he had a date with “a beautiful blonde” at a forthcoming church social.

Scopes was playing tennis on a warm afternoon in May, when a small boy appeared with a message from “Doc” Robinson, the local pharmacist and owner of Dayton’s social center, Robinson’s Drug Store. Scopes finished his game, for there is no urgency in Dayton, and then ambled on down to Robinson’s, where he found Dayton’s leading citizens crowded around a table, sipping Coke and arguing about the Butler Act. Within a few minutes, Scopes had offered himself as the sacrificial lamb. From that point, events accelerated and began to run along a predictable track. William Jennings Bryan, who had stirred millions with his “Cross of Gold” speech and almost become president as a result, was passing his declining years as a fundamentalist stumper—“a tinpot pope in the Coca-Cola belt,” as H. L. Mencken remarked. He volunteered his services for the prosecution, and Clarence Darrow responded in kind for the defense. The rest, as they say, is history. Of late, it has, alas, become current events as well.

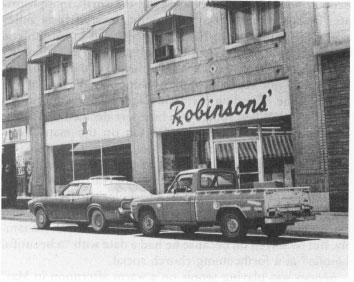

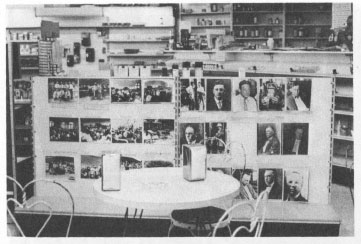

Robinson’s Drug Store is still the social center of Dayton, although it moved in 1928 to its present location in the shadow of the Rhea County courthouse, where Scopes faced the wrath of Bryan’s God. “Sonny” Robinson, Doc’s boy, has run the store for decades, dispensing pills to the local citizenry and thoughts about Dayton’s moment of fame to the pilgrims and gawkers who stop by to see where it all started. The little round table, with its wire-backed chairs, occupies a central place, as it did when Scopes, Doc Robinson, and George Rappelyea (who made the formal “arrest”) laid their plans in May 1925. The walls are covered with pictures and other memorabilia, including Sonny Robinson’s only personal memory of the trial: a photograph of a five-year-old boy, sitting in a carriage and pouting because a chimpanzee had received the Coke he had expected. (The chimp was a prominent member in the motley entourage of camp followers, many of comparable intelligence, that descended upon Dayton during the trial, in search of ready cash rather than eternal enlightenment.)

Robinson’s Drug Store, where it all began, moved to its present location in the late 1920s.

PHOTO BY DEBORAH GOULD

.

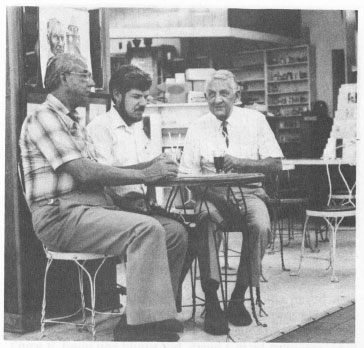

I was visiting Robinson’s Drug Store in June 1981, when a San Francisco paper called with a request for photos of modern Dayton. Sonny Robinson, who claims to be a shy man, began a flurry of calls to exploit the moment. Up north in the big town, you wouldn’t keep a man waiting, at least not without a request or an explanation: “Excuse me, I know you must be in a hurry, but would you mind, it won’t be more than a few minutes….” But it was 97° outside and cool in Sonny Robinson’s store. And where would a man be going anyway? Half an hour later, his personages assembled, Sonny Robinson pulled out the famous table and brought three Cokes in some old-fashioned five-cent glasses. I sat in the middle (“the biology professor from Harvard who just happened to walk in,” as Robinson had told his callers). On one side sat Ted Mercer, president of Bryan College, the fundamentalist school begun as a legacy to the “Great Commoner’s” last battle. On the other side sat Mr. Robinson, son of the man who had started it all around the same table fifty-six years before. The fundamentalist editor of the Dayton

Herald

snapped our pictures and we sipped our Cokes.

The interior of Robinson’s is covered with photos and other mementos of the Scopes trial.

PHOTO BY DEBORAH GOULD

.

Dayton has remained a small and inconspicuous town. If you’re coming from Knoxville via Decatur, you still have to cross the Tennessee River on a six-car ferry. The older houses are well kept, with four white pillars in front, the vernacular imitation of plantation style. (As a regional marker of the South, these pillars are architecture’s equivalent of the dependable gastronomical criterion: when the beverage simply labeled “tea” on the menu invariably comes iced.) H. L. Mencken, not known for words of praise, confessed (in surprise) his liking for Dayton:

A proper way to treat the issues that divide us. Three men of divergent views chat and sip Coke around the “original” table in Robinson’s Drug Store. Left, Ted Mercer, president of fundamentalist Bryan College; center, yours truly; right, Sonny Robinson.

PHOTO BY DEBORAH GOULD

.

I had expected to find a squalid Southern village…with pigs rooting under the houses and the inhabitants full of hookworm and malaria. What I found was a country town full of charm and even beauty…. The houses are surrounded by pretty gardens, with cool green lawns and stately trees…. The stores carry good stocks and have a metropolitan air, especially the drug, book, magazine, sporting goods and soda-water emporium of the estimable Robinson.

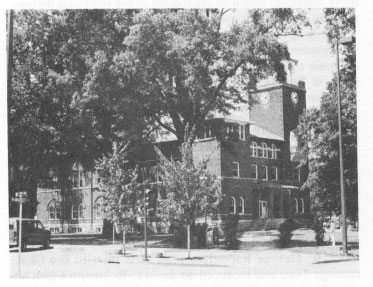

The Rhea County Court House in Dayton, Tennessee, scene of the Scopes trial.

PHOTO BY DEBORAH GOULD

.

Some things have changed, of course. Trailers now rooted to their turf and houses of undressed concrete block reflect the doubling of Dayton’s population to nearly 4,000. The older certainties may have eroded somewhat. A banner headline in this week’s Dayton

Herald

tells of a $200-million marijuana crop confiscated and destroyed in Rhea and neighboring Bledsoe counties. And a quarter gets you a condom—“sold for the prevention of disease only,” of course—at vending machines in restrooms of local service stations. At least they can’t blame evolution for this, as one evangelical minister did a few months back when he cited Darwin as a primary supporter of the four “p’s”: prostitution, perversion, pornography, and permissiveness. They taught creationism in Dayton before John Scopes arrived, and they teach it today.

For all these muted changes, Dayton remains a two-street town, dwarfed at the crossroad by the Rhea County courthouse, a Renaissance Revival building of the 1890s seemingly too large by half for a small town in a small county. Yet even this courtroom failed in its moment of glory, as Judge Raulston, noting that the weight of humanity had opened cracks in the ceiling below, reconvened his court on the side lawn, where Darrow grilled Bryan alfresco. (It is a meaningless and tangential irony to be sure, but I thought I’d mention it. Rhea was the daughter of Uranus and the mother of Zeus. Her name also applies to the South American “ostrich.” On the

Beagle

voyage, Darwin rediscovered a second species, the lesser, or Darwin’s, rhea, living in a different part of South America. In one of his first evolutionary speculations, Darwin surmised that the spatial difference between these two rheas might be analogous to the temporal distinction between extinct species and their living relatives.)