Here Comes the Night (3 page)

Berns in the Bronx

S

ID BERNSTEIN MANAGED

the Tremont Terrace, a mambo parlor about ten blocks from where he lived, while he went to Columbia, hoping to be a writer. The club was housed in a former Con Ed regional office in the Bronx and owned by a middle-aged couple who made a living renting it out for weddings, bar mitzvahs, any catered event. Bernstein started out publicizing their Friday night dances at twenty-five dollars a week. With the South Bronx becoming home to a substantial Puerto Rican population and the growing interest in Latin music around town in 1949, Bernstein and his employers decided to change the name of the place to the Trocadero and began presenting a series of Latin dances.

But it wasn’t only Puerto Ricans with their long-limbed elegant ladies who attended. Mambo fever shot through the town that year and the catering hall was thronged with blacks from Uptown and Jews from the Bronx, a rare, almost unprecedented microcosm of the city’s melting pot in a nightclub. One night Bernstein saw a young man dancing the mambo who he thought must be a movie star. The lithe young fellow not only danced with a remarkable fluid grace but also dressed beautifully. Bernstein stopped working to watch him dance. He started to notice the handsome, attractive dancer returning night after night and was eventually introduced to him by a fellow patron.

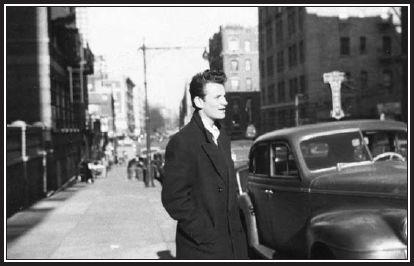

He had a wiry, coiled body and a practiced waterfall curl that landed perfectly in the middle of his forehead. His parents owned a prosperous dress shop on the Grand Concourse in Fordham, the most affluent end of the Bronx, and they dressed him well. His name was Bert Berns.

He was twenty years old, but he still played stickball in the streets. He didn’t go to school and he didn’t have a job, but he nursed vague show business ambitions. Bernstein was immediately taken with this amiable hustler. They became best of friends. They double-dated. They cruised out to Coney Island for hot dogs in the car Berns borrowed from his mother. He dazzled Bernstein playing the piano. Bernstein was even more impressed to learn that the strong, supple melodies Berns was playing he had also written. The two of them shared an eager enthusiasm for Latin music, enthralled to be working even the peripheries of this blossoming scene.

Like many young Jews in New York, Berns was smitten with the mambo. The Latin beat had only recently exploded on the New York nightlife scene, spreading out since Machito and his Afro-Cubans started playing downtown three years earlier in 1946. Cuban émigré Frank Grillo—Machito—and his brother-in-law Mario Bauza, the band’s arranger who had roomed with Dizzy Gillespie during their tenure in the brass section of the Cab Calloway Orchestra, introduced their trademark blend of Latin jazz to New York in 1940.

Bauza left Calloway, and he and his brother-in-law, who had become a regulation

rumbalero

singing with Xavier Cugat and Noro Morales, among others, finally started the band they had long been planning. Machito and his Afro-Cubans were ground zero of the Latin jazz movement in the United States. Pulling together the cream of Cuban musicians living in New York, they erected their dream orchestra that combined the daring sweep of big band jazz with the fire of Cuban rhythms. The band made its debut December 1940 at the Park Palace, a dance hall uptown in Spanish Harlem.

While Machito served out his military duty during the war, Bauza imported Machito’s foster sister, Graciela Perez, from Cuba to sing with the band. After the war, the group became the center of a gathering storm of Afro-Cuban music in New York. In 1946, Machito’s orchestra made its first appearance downtown at the Manhattan Center around the same time the Alma Dance Studio at the corner of Fifty-Third Street and Broadway in Midtown started a weekly Latin night that would become headquarters to the rapidly growing scene once the hall changed its name to the Palladium Ballroom.

The bebop revolt was in full bloom on the New York nightlife circuit, and young Turk jazzmen like Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, and others flocked to the rhythmic riches of Machito’s bandstand, jamming with the orchestra or using the band on recording dates. Pundits called the resulting hybrid Cubop. Bandleader Stan Kenton borrowed Machito’s Cuban percussion section to record his version of “The Peanut Vendor,” the song that introduced Cuban music to America sixteen years before, and the two bands played a signal double bill downtown at Town Hall in 1947.

Gillespie had formed his own big band, and his friend Bauza introduced him to

conguero

Chano Pozo, a wild-eyed, dark-skinned Afro-Cuban who brought Latin rhythms to the world of jazz. Pozo was killed the following year in 1948—shot in a fight with a drug dealer who sold him some bad dope, believing Yoruban spirits would protect him from the bullets—but he left an indelible imprint on the rhythmic blueprint of jazz.

The Palladium Ballroom was the hip place to be. Jazz musicians like Dizzy Gillespie and George Shearing hung out at the club, around the corner from the busy Fifty-Second Street jazz clubs, and a modern, young white crowd packed the dance floor, drinking in the tropical rhythms and carefree, sensual atmosphere. Marlon Brando, a struggling actor at the time, attended frequently. The Latins in the crowd used to refer to the abundant Jewish girls on the scene as “Bagel Babies.” Like

the rock and roll music that emerged a few years later from the subterranean depths of urban black music, this ethnic exotica offered a colorful, pulse-quickening alternative to the soporific sounds of the day’s puerile, lily-white hit parade. Compared to prevalent pseudo-operatic pop such as Vaughn Monroe’s “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” this music smoldered with open sensuality, not to mention the wanton forbidden thrill of the mixing of races, heady stuff for knowing youth in a country just waking from its postwar stupor.

Two other key Latin bandleaders also emerged. Tito Puente, the brilliant young timbales master who played briefly with Machito before entering the navy during the war, attended Juilliard School of Music on the G.I. Bill after the service and joined the prominent band led by former Xavier Cugat sideman Cuban pianist Jose Curbelo. In 1947, he left Curbelo and started his own

conjunto

, the Piccadilly Boys. The following year, his recording of “Abaniquito” became one of the first hits of the new New York mambo record label, Tico Records.

Also recording for Tico was the Mambo Devils, another new mambo band put together by bongo player and vocalist Tito Rodriguez, who spent five years with the great Noro Morales before playing alongside Puente in Curbelo’s group. Rodriguez had Latin lover matinee idol good looks and a warm way with a romantic ballad. His band brought together some of the top Latin players in town and was soon a regular attraction, almost the house band, at the weekly Palladium dances.

The founder of Tico Records, a handsome young Jew from Queens named George Goldner, was one of the regular dancers at the Palladium, a mambo-mad children’s clothing salesman from the Garment District in a lucky suede hat. Goldner would also become a central figure in the emergence of rock and roll and the entire independent record business. Goldner spoke Spanish, danced a fabulous mambo, and married a saucy Latin American girl. He was such a prominent fixture on the scene that musicians started to come to him for business advice and he knew them all. He borrowed money from his parents and took a

bath presenting mambo dances in Newark, New Jersey, a province the Latin music craze hadn’t yet reached. Still, he was convinced by the manager of the big Broadway record retailer, Colony Records, to start a mambo label. He borrowed more money from friends in the Garment District and, at age twenty-nine, launched Tico Records in 1949, a label that proved to be crucial in the spreading of the mambo in America. Goldner busily began to record all the emerging titans in the field, starting with Puente and Rodriguez.

The fifties was a renaissance age of Afro-Cuban music. New York’s thriving market for the music echoed the exciting, exuberant sounds coming from Havana, a destination Caribbean gambling resort and tourist trap whose rich, decadent nightlife throbbed to a tropical beat, drawn from the island’s wealth of musical folklore.

Perez Prado was a young Cuban arranger and pianist with the Havana musical institution Casino de la Playa Orchestra in 1943 when he first cautiously tried incorporating mambo rhythms into his music. It was not especially well received. He was somewhat more successful on his first road trip, playing Buenos Aires in 1947. But when he hit Mexico City the following year, the town went mambo mad. Signed to RCA Victor International, Prado relocated to Mexico City and began recording. He cut “Que Rico el Mambo” in December 1949, and, rushed to the market before Christmas, the record was an instant smash. All through Latin America, the demand for Prado records went through the roof. He released more than twenty-five singles the next year.

Prado was all shimmering brass, blasting trumpets, belching trombones, groaning saxophones, carefully layered against the tangy Cuban rhythms. There were no improvisational sections for soloists. Prado formalized the mambo, giving the rough edges a glossy sheen. He was a gaudy vulgarian who framed the sensuous essence of the mambo with a glamorous, even somewhat baroque, setting. His mambo-for-the-masses may not have earned Prado respect in the more sanctimonious quarters

of the Broadway Latin jazz crowd, but he was definitely the king of the mambo.

He played the part. Prado was quite the showman. Conducting his band with a baton, often wearing gold lamé tails and jeweled gloves, he would dance, clown, do midair leg kicks. There was no jazz in his shows. The goateed Prado would punctuate passages with his peculiar signature dog bark—the indecipherable exhortation

“Dilo!”

or “Say it!”

His success did not come so quickly in the United States. He took only his maracas player and vocalist with him to California in 1951. Armed with a book full of complicated charts, Prado threw a band together in Los Angeles, including a few players who worked with his hero, Stan Kenton, such as key trumpeter Pete Candoli, master of those piercing high notes. He rehearsed their asses off for three days and did a string of dates on the West Coast that knocked everybody dead. He drew a sold-out crowd of twenty-five hundred to Los Angeles’ Zenda Ballroom and thirty-five hundred a week later at Sweet’s Ballroom in Oakland. His Waldorf Astoria Starlight Room engagement may not have been so successful, but New York jazz snobs always wrote off Prado as not authentic. But Prado was the man who took the mambo worldwide and, in 1955, to number one on the American charts with “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White.” A cornerstone of cotillion dances for the next generation, the million-selling song was actually recorded as the theme song to a latter-era Jane Russell movie called

Underwater!

And on the record label, it said clearly—“Mambo.”

Mambo had entered the pop lexicon. Perry Como sang “Papa Loves Mambo.” Vaughn Monroe did “They Were Doin’ the Mambo.” Rosemary Clooney went so far as to try “Mambo Italiano.” Rhythm and blues records capitalized on the mambo craze, too. Ruth Brown recorded “Mambo Baby” for Ahmet Ertegun’s fledgling Atlantic Records, and on the West Coast, a pair of young white r&b songwriters, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, outfitted their vocal group the Robins with “Loop de Loop Mambo.” Even television’s favorite couple included real-life

Cuban bandleader Desi Arnaz, who first clicked in 1946 with “Babalu.” He played, well, a Cuban bandleader with his real-life wife Lucille Ball on the TV comedy

I Love Lucy

.

Arsenio Rodriguez, the great blind Cuban musician who invented the mambo in 1939—he called it

ritmo diablo

, the devil’s rhythm—himself first turned up in New York in 1947, drawn by word of a miracle operation that could restore his sight. It took the doctor an examination no longer than five minutes to tell the thirty-six-year-old Cuban bandleader that he would never see again. His optical nerves were damaged beyond repair. Later that day, after a short nap, Rodriguez summoned his brother to write down the words of a song that came to him in his sleep, and the remarkable man dictated the lyrics to his classic “La Vida Es un Sueno (Life Is but a Dream).” He may not have gotten his sight back, but he did get his first taste of this rather amazing Cuban music scene growing in America and he returned to settle in New York in 1953.

In the early fifties, the major labels basically ignored the mambo craze. The records didn’t sell in large numbers and the phenomenon appeared limited to the five New York City boroughs. That left the field open to small-time hustlers and innocent enthusiasts like George Goldner. At the Tremont Terrace, Sid Bernstein was booking all the working Latin bands into the former Con Edison building with the little balcony and the bustling kitchen in the heart of the Bronx—Machito, Puente, Rodriguez.

When Bernstein brought in rumba king Noro Morales, he met the bandleader’s younger brother, Esy Morales, who was playing flute in his brother’s band. Esy Morales had scored a hit, “Jungle Fantasy,” the year before in 1949 in a Hollywood movie and Bernstein was surprised to find him working in his brother’s outfit. Within days, he clinched a deal to manage Esy Morales, and his friend Bert Berns talked Bernstein into going into the record business. They called their company Magic Records. No kidding. It may not have been much, but they were in the record business.