Hero of the Pacific (31 page)

Read Hero of the Pacific Online

Authors: James Brady

Here is the documentation for the Navy Cross on Iwo and the citation itself, starting with the recommendation for an award: “From the commanding officer, Company C, 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, 24 April 1945,” and sent upward through the chain of command all the way to Vandegrift:

Subject: Navy Cross, recommendation for, case of Gunnery Sergeant John (n) Basilone (287506). USMC (Deceased). (A) Simple citation. (B) Statement of Witness.

It is recommended that Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone be considered for the award of the Navy Cross. On 19 February, 1945, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone was serving in combat with 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands.

On this date, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone, moving forward in the face of heavy artillery fire, worked his way to the top of an enemy blockhouse which was holding up the advance of his company. Single handed, through the use of hand grenades and demolitions, he completely destroyed the blockhouse and its occupants. Later, on the same day, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone calmly guided one of our tanks, which was trapped in an enemy minefield, to safety, through heavy mortar and artillery fire. Gunnery Sergeant Basilone's courage and initiative did much to further the advance of his company at a time vital to the success of the operation. His expert tactical knowledge and daring aggressiveness were missed when he was killed at the edge of the airstrip by a mortar blast later the same day.

This was signed by Edward Kasky.

Rereading this “simple citation,” a sort of preliminary sketching out of the facts for the authorities to review before writing and approving the formal citation itself and the award, I'm struck by several problems noted earlier in other accounts. Why would a machine-gun platoon sergeant be toting hand grenades and demolitions enabling him to knock out a blockhouse? Earlier stories seemed to indicate he destroyed the blockhouse from ground level, running toward it, not on its roof. And how is it that Basilone, just arrived on the scene, is able expertly to guide a tank through enemy minefields?

Then there is the statement of a single witness, PFC George Migyanko, dated April 24, two months after John's death: “I, George Migyanko, while serving with the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, saw Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone (287506), USMA, single-handedly destroy an enemy blockhouse which was holding up the advance of his company. Later in the day he led one of our tanks from a trap in a mine field in the face of withering artillery and mortar fire.” End of statement.

That April 24 document was approved and forwarded to the secretary of the Navy on September 13, signed by H. G. Patrick, senior member of the board looking into the matter. Attached are other endorsements from lower-ranking officers of the 27th Marines, including Gerald F. Russell on April 25, T. A. Wornham on April 27, and K. E. Rocket on May 25. On June 27, 1945, it is the commanding general himself, “Howlin' Mad” Smith, who adds a fourth endorsement and sends the whole package on to the secretary of the Navy, via the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet (Chester Nimitz, I would suppose) and to the commandant of the Corps. Next, on August 10, the commander, Pacific Fleet, sends along his approval to the secretary, again via the commandant, this letter signed by J. A. Hoover, deputy CINCPAC and CINCPON. On August 27 Vandegrift, who was by now the commandant, sends along his okay to Forrestal, the Navy secretary, noting, “recommended that Gunnery Sergeant Basilone be awarded the Navy Cross, posthumously.”

There's a little more confusing bureaucracy at work here, it seems, since James Forrestal, SEC/NAV as they say, would not date until August 12, 1946, the official award of the Navy Cross, a year after the war ended. Who can explain that one except to suggest the office rubber stamp was incorrect in dating the sheet of paper with Forrestal's signature 1946 instead of 1945 when all the other material is dated? Clearly, in wartime, paperwork in the Corps or in the Department of the Navy was often sloppy.

Here, in any event, is the final version of the citation for his Navy Cross, verbatim:

For extraordinary heroism while serving as a Leader of a Machine Gun Section of Company C, 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, 19 February, 1945. Shrewdly gauging the tactical situation shortly after landing when his company's advance was held up by the concentrated fire of a heavily fortified Japanese blockhouse, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone boldly defied the smashing bombardment of heavy artillery fire to work his way around the flank and up to a position directly on top of the blockhouse and then, attacking with grenades and demolitions, single-handedly destroyed the entire hostile strongpoint and its defending garrison. Consistently daring and aggressive as he fought his way over the battle-torn beach and the sloping, gun-studded terraces toward Airfield Number One, he repeatedly exposed himself to the blasting fire of exploding shells and later in the day coolly proceeded to the aid of a friendly tank which had been trapped in an enemy mine field under intense mortar and artillery barrages, skillfully guiding the heavy vehicle over the hazardous terrain to safety, despite the overwhelming volume of hostile fire. In the forefront of the assault at all times, he pushed forward with dauntless courage and iron determination until, moving upon the edge of the airfield, he fell, instantly killed by a bursting mortar shell. Stout-hearted and indomitable, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone, by his intrepid initiative, outstanding professional skill and valiant spirit and self-sacrifice in the face of fanatic opposition, contributed to the advance of his company during the early critical period of the assault, and his unwavering devotion to duty throughout the bitter conflict was an inspiration to his comrades, and reflects the highest credit upon Gunnery Sergeant Basilone and the United States naval Service. He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.

Among the multiple copies one is directed to “Public Info,” and with a brief notation at the bottom, “Raritan, New Jersey . . . Buffalo, New York,” I assume this meant that the media in those two cities, of John's rearing and his birth, were to be notified of the honor.

It is the accuracy of details in these battle accounts of Basilone's conduct that comes under criticism. But despite all the brass in Washington signing off on his Navy Cross, there remain to me some questions. We know Basilone was brave, a great Marine, a heroic man. But where did the blockhouse-busting grenades and demolitions come from? Was he on the blockhouse roof or down below? Was he really waving a hunting knife around? How was he sufficiently familiar with alien ground to guide that tank through the mines? Was he killed instantly by that mortar? Then why all those accounts of his living for hours, speaking with the corpsman, dictating messages to be passed on to brother George, and gradually bleeding to death? And what about that sole witness, the private who signed the citation recommendation? Where were the others? Questions remain.

Epilogue

Despite what Bertolt Brecht said, I believe having national heroes is healthy, giving us people to admire, role models, perhaps helping us to

be

somehow better than we are. Maybe heroes are just plain good for us; they make us feel better about ourselves, about the country, to know that among us are men and women who under pressure behave in exemplary ways and do things most of us don't even try. And it's not only wars that make heroes; newspapers and the local television stations regularly run features about “everyday heroes,” urging nominations. There was even a time when America really

needed

a hero like John Basilone.

be

somehow better than we are. Maybe heroes are just plain good for us; they make us feel better about ourselves, about the country, to know that among us are men and women who under pressure behave in exemplary ways and do things most of us don't even try. And it's not only wars that make heroes; newspapers and the local television stations regularly run features about “everyday heroes,” urging nominations. There was even a time when America really

needed

a hero like John Basilone.

I'm neither a scholar nor a historian, just another old newspaperman who once fought in a war, but I remain fascinated and often puzzled by John Basilone, a professional Marine machine gunner in two climactic battles, one at the very start of a Pacific war we were losing and then in a second fight near the end of a war we knew we were going to win. He was a man already dead when I was a Catholic high school boy reading about him in the

Daily News

, and most of what I later knew of Basilone came from Marines and Marine Corps lore and the memories of old men in New Jersey, what they told me, the black-and-white photos at the Raritan library, when they drove me to the big bronze statue and took me to visit the little frame boyhood home, to see his hangouts.

Daily News

, and most of what I later knew of Basilone came from Marines and Marine Corps lore and the memories of old men in New Jersey, what they told me, the black-and-white photos at the Raritan library, when they drove me to the big bronze statue and took me to visit the little frame boyhood home, to see his hangouts.

I mentioned earlier a resemblance to the youthful Sly Stallone. Basilone

was

Stallone's Rambo, a real-life Rambo. And despite the wars and the years that separate the generations of Marines, I feel I knew a man I never metâbecause every Marine knew Manila John.

was

Stallone's Rambo, a real-life Rambo. And despite the wars and the years that separate the generations of Marines, I feel I knew a man I never metâbecause every Marine knew Manila John.

Even though . . .

More than sixty years after his death at age twenty-eight on Iwo Jima, Basilone remains an enigma. There are still questions about the famous decorations for his heroic battles. Some of these are insignificant points, matters of detail, an incorrect stat here, a confusion of names there, the chaos of battle, the tendency of loved ones to boast a little. Other questions were more substantive. This was the exasperating part of Manila John's story.

It goes without saying that neither sergeant, Mitchell Paige nor Basilone, campaigned for a decoration of any sort, never mind the top medal we have. Marines don't recommend themselves for awards; their superiors write them up.

The Navy Cross awarded posthumously on Iwo Jima is a strange affair, more complicated than any doubts about Guadalcanal. And being dead, Basilone can have no responsibility for what was subsequently written, said, or sworn to. The facts seem to be that Gunny Basilone, when confronted by a Japanese blockhouse, did precisely what the moment called for. He demonstrated initiative by getting a demolition assault team to send a man forward with a heavy explosive charge and another, the giant William Pegg, with the flamethrower, while Basilone's machine gunners gave them overhead covering fire.

Sergeant Basilone did his job perfectly, and so did the demo guy and the flamethrower, as did Basilone's machine gunners. The Japanese position fell to the combined Marine operation of explosives, flame, and machine-gun fire, and the stalled Marine drive inland got going, thanks in large part to Basilone's gutsy, intelligent leadership.

If that's the story, those the precise factsâand Chuck Tatum, there as a machine gunner, writes that they wereâit is both rational and believable. If “Sergeant Basilone directed this operation âby the book,' the way we practiced it at Pendleton and Camp Tarawa,” then why conjure up a fantastic story about how Basilone scaled the roof and single-handedly destroyed the position with grenades? Or spent his time waving a hunting knife around, taunting and capering?

Basilone made the thing happen. It wasn't a solo performance, but it was heroic. Two other men backed up by his machine guns carried it out.

Then reread the official Navy Cross citation. The story of the tank in the minefield. Why pad the already impressive résumé? Did the Department of the Navy have so much invested in Basilone that he couldn't just die, he had to die gloriously, capable of superhuman feats? Maybe they had to make it up to America for permitting its hero to go back one more time to the battle. How else do you justify an official citation signed off by so many while so rife with apparent exaggerations?

Maybe, as has been charged, the Basilone of the war bond tour, with his handlers and packaged speeches and appearances, was to an extent a product marketed and merchandised by imaginative young officers doing PR for the Marine Corps. They were out to sell inspiration to a country that needed heroes, and Basilone must have looked like a good bet, a superior salesman. The kid out of Raritan was everyman from everywhere, an ordinary Joe, a small-town American; the darkly handsome, undefeated boxer Manila John, a poker-playing roughneck from the caddy shack, the guy with a knockout punchâand that marketable nickname. If this is true, none of it was Basilone's idea.

Basilone has surely been ill served even by people who loved him, family and friends, and by others, publicity professionals and inventive journalists, who damaged his reputation with fanciful stories and memoirs, their cartoon-styled exaggerations of feats of arms never performed, the hero lost behind his deeds.

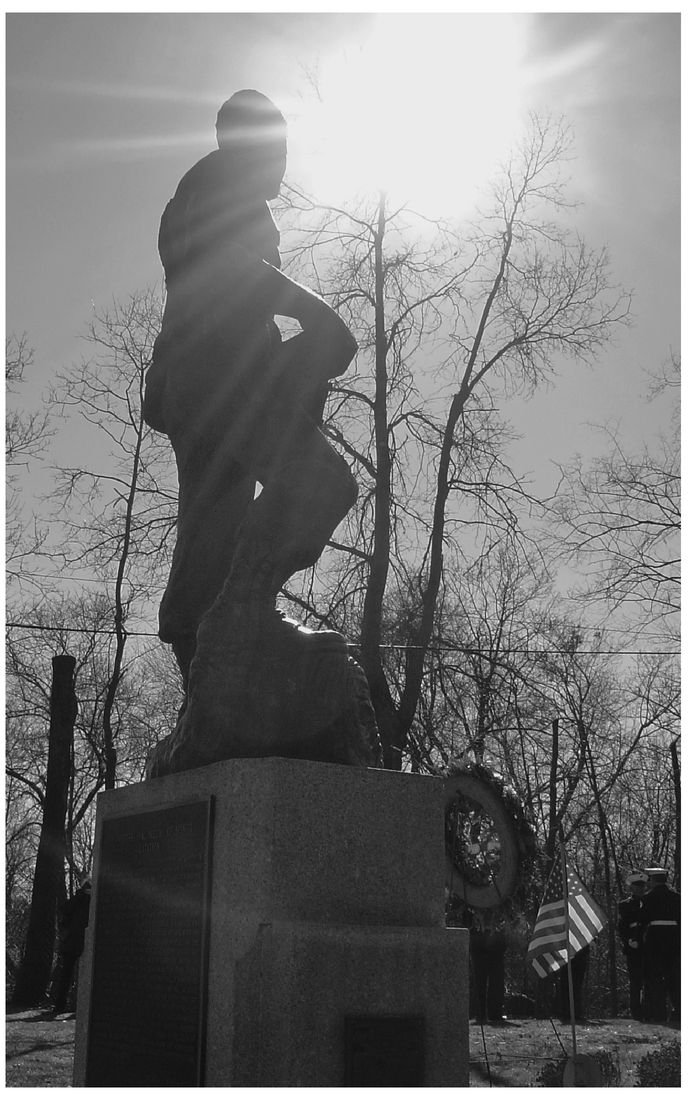

The Basilone statue in Raritan, New Jersey, haloed by the sun.

But this is what makes him a legend and an American icon. Maybe we should just embrace the colorful lore, memorialize John Basilone as a Marine and honor his service, take him on faith, forget the disputation and the skeptical theories, mine and others, and just love the guy, saluting him with a well-earned and final Semper Fidelis. Always faithful. Perhaps we should leave it just as simple and as wonderful as that.

Bibliography

This bibliography was compiled from the author's notes after his passing. Any omissions or inaccuracies are, therefore, those of the editor.

Other books

Full Bloom by Jayne Ann Krentz

Enchanter's Echo by Anise Rae

Xtreme by Ruby Laska

Wisdom's Kiss by Catherine Gilbert Murdock

Sweet Scent of Blood by Suzanne McLeod

No Return (The Internal Defense Series) by Zoe Cannon

Death's Last Run by Robin Spano

Pies & Peril by Janel Gradowski

Spring Training by Roz Lee

Locked In by Kerry Wilkinson