Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (29 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

After lunch, the three of them proceeded to the mound, where Bell observed the men excavating and condemned the methods being used as “prehistoric” (she was notoriously outspoken and critical), compared with those of the Germans. Lawrence maintained that the German methods, while they looked neater, involved a great deal of reconstruction, but eventually they made peace over dinner, and parted friends and mutual admirers when she retired to the tented camp Fattuh had set up for her. They would remain friends until her death, despite many furious arguments. On her departure, at five-thirty in the morning, Bell was dismayed that the villagers gathered to jeer at her—she did not realize that they assumed she had come to Carchemish to marry Lawrence. In order to calm them Lawrence had explained that she was too plain and old for him.

Hogarth was not certain that it was worth continuing the dig at Carchemish for a second season, but, always looking out for Lawrence’s interests, suggested that he might benefit from a season or half a season of “tomb digging” for the great Flinders Petrie, the dean of Egyptian archaeology and the head of the British School of Archaeology in Cairo. This would represent a substantial step up in Lawrence’s professional qualifications as an archaeologist, a career about which Lawrence remained nevertheless unsure—he toyed with the idea of becoming a newspaperman or a novelist, and continued to speculate on how best he might find a local source of fine vellum, to be “stained [purple] with Tyrian die,” for the artistic binding of the books that he and Richards were still planning to print. Meanwhile, Hogarth, never one to delay once a plan had occurred to him, wrote about Lawrence to his colleague Petrie: “Can you make room on your excavations next winter for a young Oxford graduate, T. Lawrence, who has been with me at Carchemish? He is a very unusual type…. If he goes to you he would probably come on foot from north Syria. I may add that he is extremely indifferent to what heeats or how he lives. He knows a good deal of Arabic…. I can assure you that he is really worth while.”

Lawrence did not learn until early in June that the excavation in Carchemish was to go on until August, though perhaps without a second season. By now the level of the Euphrates was falling, exposing sandbanks and islands, and the area was experiencing a plague of locusts, one of which he dried and sent to his youngest brother, Arnie. There was also an invasion of vast numbers of fleas and biting sand flies as the weather warmed. The constant company of Thompson seems to have been getting on his nerves—"any little thing upsets [him],” Lawrence remarked.

Lawrence was making something of a name for himself by producing miracle cures with such things as ammonia and Seidlitz powders, a popular nineteenth-century remedy for stomach distress which fizzed and bubbled furiously when added to water, and which terrified the Arabs, who had never seen such a thing. One of the two “water boys” was persuaded to take half a glass, and this is the first mention in Lawrence’s letters of his name: Dahoum.

Dahoum means “darkness,” and may have been an ironic nickname, in the same spirit that the friends of a very short man might call him “Lofty,” or a very tall man “Tiny,” since Dahoum seems in fact to have had rather light skin for a boy of mixed Hittite and Arab ancestry (his family actually lived on the Carchemish mound). He has been described as “beautifully built and remarkably handsome,” but in photographs taken of him by Lawrence (and in a pencil sketch made of him by Francis Dodd, when Lawrence brought Dahoum and Sheikh Hamoudi home to Oxford in 1913) he looks not so much beautiful—his face is a little fleshy for that, very much like the faces on the Hittite bas-reliefs that Lawrence was uncovering—as good-humored, intelligent, and amazingly self-possessed for such a young man. It is possible that Dahoum’s real name may have been Salim Ahmed—he was also referred to at least once as Sheikh Ahmed too, but that may have been one of Lawrence’s private jokes. In any event, Dahoum, who was fourteen when Lawrence met him, would play a role of increasing importance in Lawrence’s life, and becameone of the many bonds which would tie his life firmly to the Middle East, in peace and in war, over the next seven years.

As the heat increased, Lawrence took to sleeping on the mound, overlooking the Euphrates, and getting up at sunrise to help Sheikh Hamoudi pick the men, and deal with the infinite problems of blood feuds and rivalry between those who shoveled, and thought of themselves as an elite, and those who merely carried baskets of dirt and rocks. Daily, Lawrence was learning not only colloquial Arabic, but the complexities of Arab social relationships, and the dangerous consequences of getting these wrong, or offending Arabs’ sensitivity.

On June 24, he wrote home to say that the British Museum, disappointed in the results so far, had ordered work shut down in two weeks, and that he intended to take a walking tour of about a month. He added a warning, “Anxiety is absurd.” If anything happened to him, his family would hear about it in time. Dahoum had apparently been promoted from one of the two water boys to “the donkey boy,” and Lawrence described him as “an interesting character,” who could “read a few words (the only man in the district except the liquorice-king) of Arabic, and altogether has more intelligence than the rank-and-file.” Dahoum, he mentions, had hopes of going to school in Aleppo, and Lawrence intended to keep an eye on him. Lawrence deplores the intrusion of foreign influence, particularly French and American, on the Arabs, and adds: “The foreigners come out here always to teach, whereas they had much better learn.” In a postscript he adds that he has now decided to spend the winter walking through Syria (his new pair of boots has arrived), perhaps settling in one of the villages near Jerablus for a time, possibly in the house of Dahoum’s father.

This information may not have alarmed the Lawrence family, but it should have. There was no more talk of working under Petrie in Egypt, let alone any mention of Richards and his printing press. Lawrence and Thompson were to go off and briefly examine another Hittite mound at Tell Ahmar, at Hogarth’s request, and after that Lawrence proposed to go onby himself, walking to those crusader castles he had not already seen. On top of his next letter, written on July 29, from Jerablus, his mother wrote: “This letter was written when he was almost dying from dysentery.”

Lawrence’s letter home gives no hint of this—on the contrary, he writes, “I am very well, and en route now for Aleppo,” and describes his itinerary so far. The letter is unusually short for him, however—surely a bad sign—and in fact, on the day before, he wrote in his diary, “Cannot possibly continue to tramp in this condition,” and collapsed in the house of Sheikh Hamoudi. Hamoudi looked after Lawrence as best he could—though not without a note from Lawrence absolving him of responsibility in case his guest died. This was intended to protect Hamoudi from the Turkish authorities, who would certainly have punished him if a foreigner had died in his care.

Lawrence’s mother was not wrong—he came very close to dying, and owed his life to the patient and determined care of Sheikh Hamoudi and the donkey boy Dahoum. By the first days of August Lawrence was beginning to recover, though he was still very weak, and sensibly concluded that his walking tour could not be completed, and that he would have to go home. His illness in 1911 set a pattern that would persist for the rest of Lawrence’s life—he ignored wounds, boils, abrasions, infections, broken bones, and pain; paid no attention to the precautions about food and drinking water that almost all Europeans living or traveling in the East made sure to take; suffered through repeated bouts of at least two strains of malaria; and kept going as long as he could even when dysentery brought him to the point of fainting. He lived at some point beyond mere stoicism, and behaved as if he were indestructible—one of the essential attributes of a hero.

As Lawrence slowly regained his strength, he used the time to encourage Dahoum’s “efforts to educate himself,” and wrote to his friend Fareedeh el Akle at the American mission school in Jebail for simple books on Arab history for his pupil—if possible, books untainted by western influence or thinking. In the meantime he practiced his Arabic on Dahoum; and with a curious habit of anticipating the future, whichcreeps into his letters and diaries, he wrote to Hogarth that “learning the strongly-dialectical Arabic of the villages would be good as a disguise” while traveling.

While Lawrence lay ill in Jerablus, Hogarth was busy in London, deftly guiding the British Museum toward supporting a new season of digging at Carchemish, since the Turkish government was unlikely to allow the British to start excavation on another Hittite site before this one had been fully exploited. Apparently impressed by Hogarth’s letters to the Times about Carchemish, Lawrence began what was to become a lifelong habit of writing to the editor of the Times about matters that displeased or concerned him. He broke into public print for the first time with a savagely Swiftian attack on the way the Turkish government was allowing important antiquities and archaeological sites to be torn down by developers. “Sir,” he began: “Everyone who has watched the wonderful strides that civilization is making in the hands of the Young Turks will know of their continued efforts to clear from the country all signs of the evil of the past.” Remarking on a plan to destroy the great castle of Aleppo for the benefit of “Levantine financiers,” and on plans to do the same at Urfa and Biridjik, he went on to attack the Germans who were building the Berlin-Baghdad railway, and predicted that “the [Hittite] ruins of Carchemish are to provide materials for the approaches to a new iron girder bridge over the Euphrates,” signing himself, “Yours, &c., Traveller.” The Times, always quick to publish even the tamest of letters—and this one was anything but tame—under a provocative headline, published it on August 9, below the headline “Vandalism in Upper Syria and Mesopotamia,” predictably eliciting an infuriated reaction from the German consul in Aleppo. Taunting the Turks and attacking the Germans for their activities in the Ottoman Empire was to become a habit with Lawrence in the years remaining before the outbreak of war.

On August 3 Lawrence began his trip home. He arrived in Beirut on August 8, and to his great delight met the poet James Elroy Flecker and Flecker’s Greek wife, Hellé, who were to become his close friends over the next few years. Flecker was the acting British vice-consul in Beirut;he had attended Trinity College, Oxford, where he had been, or felt he was, a misfit, although he had been a contemporary, friend, and rival of the poet Rupert Brooke. John Maynard Keynes, who had met Flecker while visiting friends in Oxford, wrote about him to Lytton Strachey: “I am not enthusiastic about Flecker,—semi-foreign, with a steady languid flow and, I am told, an equally steady production of plays and poems which are just not bad.” There may be a trace of what might now be called gay bitchery in this comment, as well as a degree of genteel anti-Semitism—both Keynes and Strachey were members of a rather refined group of extremely bright, ambitious young homosexuals. Flecker labored under numerous erotic and familial difficulties, none of which he was able to reconcile or resolve: he had been educated at a school where his father was the headmaster, and as if that were not difficult enough, his father was a ferociously Low Church, evangelical Protestant who was half Jewish. Flecker’s swarthy looks made his intense Englishness seem adopted rather than natural, and he rebelled against his parents in every way, running up reckless debts, and indulging himself by writing extravagantly garish poetry and striking exaggerated aesthetic poses that alarmed them. Only by dint of a heroic, last-ditch effort was Flecker able to squeak through the examination into the consular service (a large step down from the more socially and intellectually distinguished diplomatic service). In the process, he did nothing to please either his parents or the Foreign Office by falling in love with a forceful young Greek woman, who braved the issue of his ill health—he was already suffering from tuberculosis—to marry him. More or less exiled to a subordinate post in Beirut, Flecker paid more attention to his career as a poet than to his consular duties.

In Lawrence he found not only a friend but an admirer. Lawrence was deeply impressed by Flecker’s poetry,

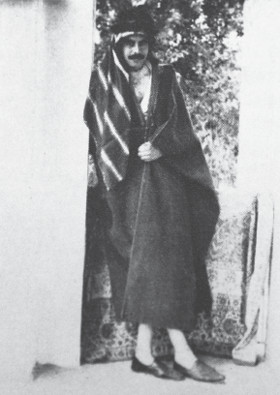

*

the best of which was written after Flecker was exposed to the color and drama of eastern life, and felt as much at home in the Fleckers’ apartment in Beirut as he would a fewyears later in that of Ronald Storrs, in Cairo. Indeed Lawrence photographed Flecker elaborately dressed in a Bedouin robe and headdress—though despite his dark complexion and an inherent love of dressing up in costume, Flecker does not look nearly as comfortable in Arab clothing as Lawrence. Flecker is also a good example of one of Lawrence’s most endearing characteristics: once he became your friend he was your friend for life, and once he admired your work he was a supporter of it forever.

It is a measure of how ill Lawrence had been that he returned to England via Marseille and went on from there by train to Oxford—this route was much quicker (and more expensive) than traveling by sea from Beirut to England. At home, he recuperated under the watchful eye of Sarah, and faced the difficulties so common to talented young men of his age. In his case it was not so much that he couldn’t decide what to do with himself as that he had too many choices and self-imposed obligations. Hogarth, he learned, had secured the funds for a second season of excavation at Carchemish; Flinders Petrie had accepted him for a stint of tomb digging in Egypt; Vyvyan Richards was still eager to proceed with the printing press scheme; Jesus College expected to hear more about Lawrence’s BLitt thesis on medieval pottery; and Lawrence himself was deeply mired in his plan to bring out his expanded BA thesis on castles and fortifications as a book, a project that was doomed for the moment by the number of his drawings and photographs that he deemed essential to the text.