Hetty Feather (2 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

'No chance of forgetting this one. Miss Hetty

Feather. I'm not sure you'll want her, missus. She

might be little but she's a shocker for screaming.

She's been squealing like a pig ever since we left

London.'

'Oh well, it shows she's got spirit,' said a voice.

'Let's have a squint at her then.'

I was placed in strong arms, my face pressed

against a very large soft chest. I snuffled against

her. She smelled of strange new things, lard and

cabbage and potatoes, but she also smelled of sweet

milk. I opened my lips eagerly and I heard laughter

all around.

'There! She's smiling at you, Mother! She's taken

to you already!'

I was stunned. This was not my real mother.

Was she a

new

mother? She held me in one arm,

my basket baby brother in the other. Her large

hands held us safe as she walked out of the station,

children clamouring about her.

'I dare say you'll do a good job with them,

missus. You bring on the scrawny ones something

wonderful,' said the basket-carrier.

'It's a bit of challenge, two little ones together,

but I dare say I'll manage,' she said. 'Let's take you

home and get you fed, my poor little lambs,' she

murmured in our ears.

We had a home. We had a mother. We were safe.

We never had to go back to the great chill baby

hospital again.

Don't mock, I say! I was only a few weeks old. I

didn't know any better.

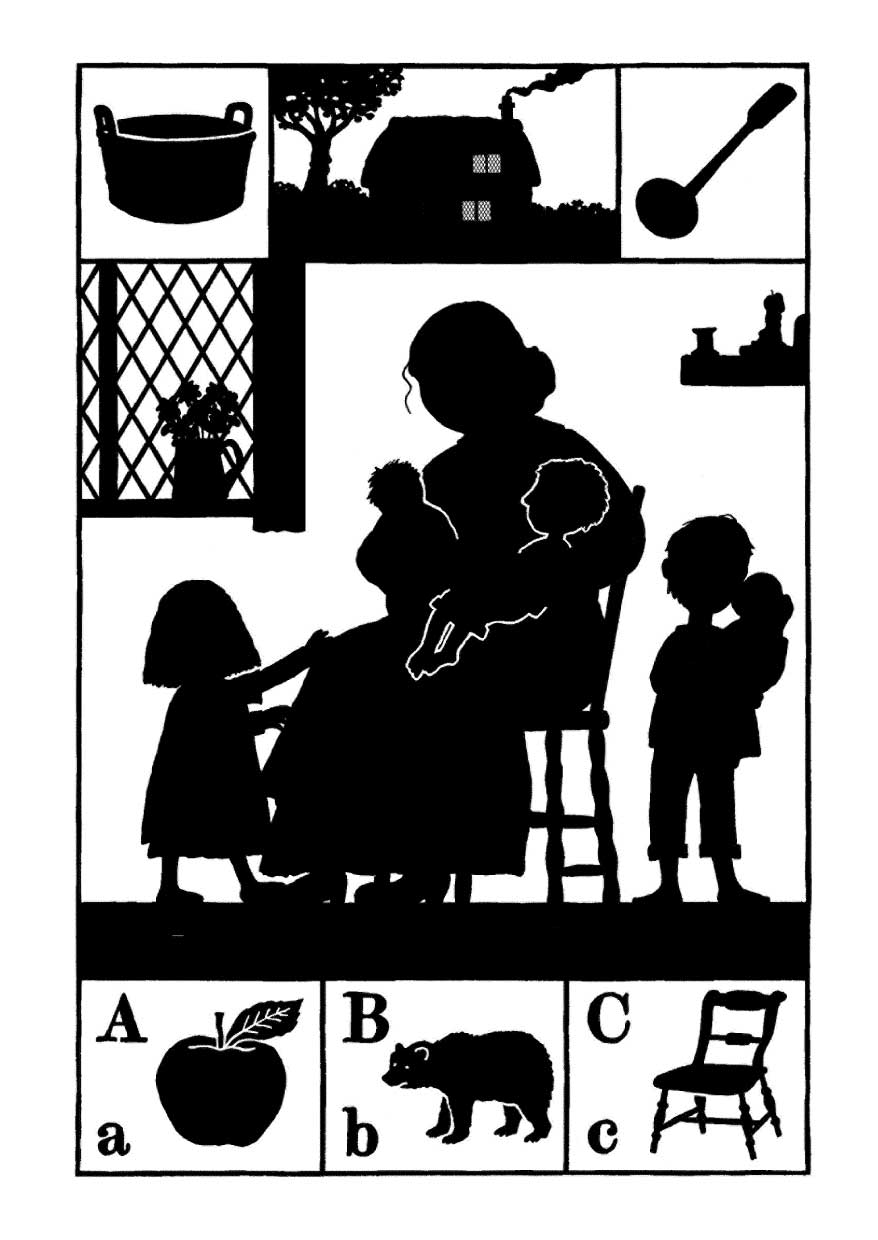

My new home was a small thatched cottage with

whitewashed walls, and roses and honeysuckle

hanging around the front door. It was small and dark

and crowded inside. It smelled of cooking all the

time, plus strong yellow soap on a Monday, washday.

That was

our

washday too. When the sheets and all

our shirts and frocks and underwear were flapping

on the line, our mother, Peg, popped all us children

in the clothes tub. Gideon and I were tossed in

first. Gideon always cried, but I bobbed up and down

like a duckling and only wailed if Mother rubbed

soap in my eyes.

Gideon was my foundling brother, my baby

travelling companion in the basket. He was not

much bigger than me, a pale, spindly baby with a

thatch of black hair and large eyes that fixed you

with a mournful stare.

'There's not enough meat on these two together

to bake into a pie,' said our new father, John.

He poked both of us in our belly buttons. It was

a playful poke but we both shrieked. We weren't

used to big, loud father people. All men were big

and loud to us babies, but when we were older we

saw that John was the tallest man in the village,

with arms like tree trunks and a belly like a barrel.

His voice was so loud his holler could carry clear

across five acres. He was as strong as the huge shire

horses he used to plough the land. No man dared

argue with him because it was clear who would

win – but Peg wasn't the slightest bit frightened

of him.

'Get away from my new babies, you great fat

lummox,' she said, slapping his hands away. 'You're

scaring them silly. Don't cry, my lambkins, this is

just your father, he don't mean you no harm.'

'Chickee-chickee-chickee, coochie-coochie-coochie,'

said Father, tickling under our chins with his big

blunt fingers. We screamed as if he was a storybook

ogre about to snap our heads off our necks.

'Get out of it,' said Peg, flapping at him with

a towel. She gathered Gideon and me up out of

our improvised bathtub and wrapped us together

in the towel, warm from the hearthside. She held

us close against the vast pillow of her bosom and

we stopped crying and snuffled close to our

new mother.

'My

muvver!' said Saul, swotting at us with his

hard little fists.

He was just starting to walk, though he had a

withered leg so that he limped. Father had fashioned

him a little wooden crutch. Saul used it to prod

Gideon and me. He hated us because he wanted

Mother all to himself.

'There now, my little hoppy sparrow. You come

and have a cuddle too,' said Peg, hauling him up

into her arms alongside us.

'And me, and me!' said three-year-old Martha,

burrowing in. Her eyes were weak, and one of them

squinted sideways.

Jem held back, his chin held high.

'Don't you want to come and join in the cuddle,

Jem dearie?' said Mother.

'Yes, but I'm not one of the babies,' said Jem

stoutly. 'I'm five. Nearly.'

'Yes, my pet, you're my big boy – but you're not

too big to say no to a cuddle with your old mum.

Come here and meet your new brother and sister.'

I was wriggling and squirming, squashed

by Saul.

'Here, Jem, you take little Hetty for me,' said

Peg. 'Ain't she tiny? You were twice her size as a

baby. She's had a bad start in life – both the babies

have, bless them. Still, we'll soon fatten them up,

just you wait and see.'

I nestled in Jem's arms. He might still be a

little boy not yet five but he seemed as strong as

our father to me – but nowhere near as frightening.

Jem's hands cupped me gently.

'Hello, little Hetty. I'm your brother Jem,' he

said softly, rubbing his face against mine.

I couldn't speak but my lips puckered and I gave

him my first real smile.

Jem wasn't the eldest. He was the youngest child

who really belonged to Peg and John. They also had

Rosie and Nat and Eliza, and there were more still

– Marcus, who'd gone off to be a soldier, and Bess

and Nora, who were away in service.

All these children – so many that your head must

be reeling trying to keep count of them all!

I

find it

hard enough to sort them all out in my head. The

older ones kept themselves separate from us younger

fostered foundlings, though Eliza sometimes liked

to play schools with us.

She lined us all up in a row by the front step and

asked us to add two and two and recite the

alphabet. At first Gideon and I couldn't even sit

up by ourselves, so we clearly had no chance of

coming top in Eliza's school. She lisped our answers

for us, and answered for Saul and Martha too.

She didn't have to invent replies for Jem. He

knew simple sums and could read out of

The Good

Child's ABC.

'A is for Apple. B is for Bear. C is for Chair. D is

for Daisy. E is for Elephant.'

I could chant my own way through by the time I

was two. Eliza fancied herself a teacher and sat us

in the corner if she felt we were stupid and caned us

with a twig if we protested.

Jem was the true teacher. He showed me

how to eat up my porridge and my mash-and-

gravy and my tea-time slices of bread and jam.

'That's right, you're a baby bird. Open your beak,'

he said.

I opened my mouth wide and then smacked my

lips together, swallowing every morsel, though I was

a picky eater and fussed and turned my head away

when Mother tried to feed me.

We didn't have any toys. Mother would have

thought them a waste of money. She didn't

have

any money anyway. However, Jem found a red

rubber ball in a rubbish heap. He washed it well

and polished it so it shone like an apple. He flung

it high into the air and caught it nine times out of

ten, and then kicked it from one end of the village

to the other.

'Me, me, me!' I said, on my feet now, but still

so little that I toppled over when I tried to kick

too.

The others laughed at me, especially Saul, but

Jem held me under my arms and aimed me at the

ball until one of my flailing feet connected and gave

it a feeble little kick.

'There, Hetty, you can kick the ball, just like me!'

he said, hugging me.

He sat beside me on the front step and drew me

pictures in the dust with his finger. His men and

women were round blobs with stick arms and legs,

his babies were little lozenges, his animals barely

distinguishable one from the other, but I saw

them through Jem's eyes and clapped and crowed

delightedly.

He helped me toddle down the road to the stream

and then held me tight while I splashed and squealed

in the cold water. If I kept my legs still while he

dangled me, the minnows would come and tickle

my toes.

'Fishy fishy!' I'd shriek.

Sometimes Jem turned his hand into a fish and

made it swim along beside me and nibble titbits

while I laughed.

When I grew bigger, he pushed me in a little cart

all the way to the woods and showed me red squirrels

darting up the tree trunks.

'That's where they've got their houses, right up

in the trees,' said Jem. 'Shall

we

have a squirrel

house, Hetty?'

He knew an old oak that was completely hollow

inside. He stood on one of the great spreading

roots, lifted me up, deposited me inside the tree

and squeezed in after me. There! We were in our

very own squirrel house. We were only a foot or so

from the ground but it felt as if we were right up in

the treetops.

'There, little Miss Squirrel. Are you happy in

your new house?' Jem asked, poking me gently on

my button nose.

'Yes, Mr Squirrel, yes yes yes!' I said happily.

I loved our little treehouse so much I didn't want

to go home for tea. I shook my head and protested,

clinging to the bark with my fingertips. Jem had to

carry me home kicking and screaming. I wouldn't

be quiet until he promised we'd play there the very

next day.

I went leaping onto the boys' bed at five o'clock

in the morning, before Father and Mother were

stirring, demanding that Jem keep his promise.

He stayed true to his word, even though I was

behaving like an almighty pest. He carted me back

to our house in the woods straight after breakfast.

He patiently ate another pretend breakfast of acorns

and grass, and he helped me care for my squirrel

babies (lumps of mud wrapped in dock leaves). He

even lined the floor of our house with moss and

sprinkled it with wild flowers to make a pattern on

our green carpet.

I stupidly babbled about our wondrous

squirrel house that bedtime, and of course all the

other children wanted to come and see it too, even

Rosie and Eliza. Nat sneered at Jem for playing

a girly game of house with a baby, but Jem was

unruffled.

'I

like

playing with Hetty, it's fun,' he said, and

my heart thumped with love for him.

I wanted to keep the squirrel house just for

us, but Jem was far too good-natured. 'Of course

you can all come a-visiting,' he told everyone. But

then he added, 'But you must remember, it's

Hetty's

house.'

I didn't mind Gideon coming. He was my special

little basket brother and I loved him second best

to Jem. I was a few days older than Gideon but he

was a half a head taller than me now, though still

ultra-spindly, his neck and wrists and ankles so

thin they looked in danger of snapping. Mother

took it to heart that he looked so frail and sneaked

him extra strips of bacon and a bite of Father's

chop, but the ribs still stuck out on his chest and

his shoulder blades seemed about to slice straight

through his skin.

Mother tried to encourage him to run about and

play in the sunshine with us, but he preferred to

cling to her skirts and climb on her lap whenever

she sat down to shell peas or darn stockings.

I could sometimes tempt Gideon away to play,

though he was incredibly tiresome when it came to

my special picturing games.

'Listen, Gideon. Let's picture we're in the woods.

We're lost and a huge huge huge howling wolf is

going to eat us all up,' I'd say.

Gideon would start and tremble, and when I

growled he ran screaming for Mother. She'd scoop

him up in her arms and aim a swipe at me.

'Stop scaring the poor little mite senseless,

Hetty. I'll paddle you with my ladle if you don't

watch out.'

I'd been well and truly paddled several times

and I didn't enjoy the experience. I didn't mean

Gideon any

harm.

It wasn't

my

fault he was

such a little milksop. But I smiled at him even

so, and said he could come and visit my squirrel

house. I let him squeeze into the cart with me

while poor Jem puffed along pushing the two

of us.

Gideon squirmed uneasily as I chatted about my

house. 'Squirrels might bite,' he said fearfully.

'Oh, Gideon,

squirrels

don't bite! We'll bite

them,'

I said, giggling.

'Can't climb up the tree, Hetty,' Gideon wailed.

'It's easy, Gideon. I can climb. Jem can too,'

I said.

'I might fall!' said Gideon, nearly in tears.

'Don't cry, Gideon. You won't fall. Just

think, you're getting to see my squirrel house and

Saul

isn't.'

'Saul can come too,' said Jem quickly. 'And

Martha.'

'No they can't – too much of a squash,' I said,

wishing Jem wasn't always so kind. I just wanted

him to be kind to

me.

It was a waste of our kindness inviting Gideon.

To help him appreciate the charm of the squirrel

house I made us 'climb' in the air for several seconds

before we hopped up into the hole in the tree. This

was fatal. He clung to me desperately.

'Whee –

we're right up in the treetops! See the

birds flying!' I said.

'Have to get down! It's too high, too high!' Gideon

said, peering down fearfully, though if he reached

right out he could put his hand on the ground.

'It's not

really

high, Gideon, look,' said Jem,

dangling his leg down.

'Hetty makes it high!' said Gideon.

Jem laughed. 'That's what she's best at, picturing.

She's grand at it.'

'I wish she wasn't,' said Gideon, and he closed

his eyes tight, as if he could shut out my picturing

that way.

Gideon stayed in the cottage with Mother when

Jem made me take Saul and Martha to the squirrel

house. That was a waste of time too. I didn't mind

Martha, but she was so near-sighted she had no idea

what a squirrel

was.

She sat in the tree and blinked

solemnly, waiting for something to happen. I served

her tea in an acorn cup and gave her a slice of fairy

bread on a leaf, and she tried to eat and drink politely,

but she looked puzzled when there was nothing in

her mouth. She started to eat the leaf itself and Jem

had to prise it out quickly lest she was sick.

I'd have happily stuffed a whole

tree

of leaves

down Saul's throat.

'This is a stupid place. It's not a

real

squirrel

house. That's not a fine green rug, that's moss.

That's not china, it's leaves. They're not babies.

They look like pig poo.

Dirty

Hetty, playing with pig

poo.'

I pushed him hard in the chest, because no mother

can stand to have her babies insulted. I pushed a

little too hard. Jem tried to catch him but he wasn't

quite quick enough. Saul fell right out of my squirrel

house. It truly wasn't far, and any other child would

have jumped up again and laughed – but not Saul.

His eyes slid into slits and his mouth went square.

'You've hurt my poorly leg!' he bawled. 'I'm telling

Mother!'

Oh dear. Gideon was clearly Mother's favourite,

but she had a particular soft spot for Saul, Lord

knows why. She fussed over his leg, rubbing it with

different remedies – goose grease and witch hazel

– and knitted him a special soft pair of stockings

because his boot rubbed his twisted foot. Saul

enjoyed this attention and exaggerated his limp in

front of Mother for all he was worth.