Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (10 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

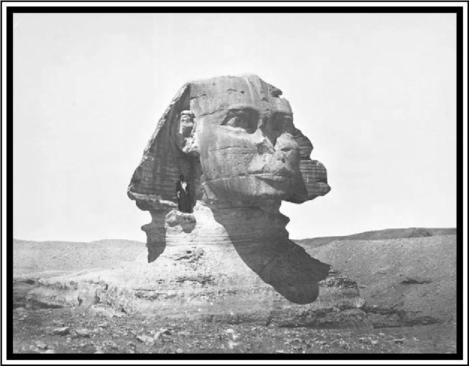

Despite this clearing, the colossal

sculpture soon found itself beneath the

sand once again. When Napoleon arrived in Egypt in 1798, he found the

Sphinx without its nose. 18th century

drawings reveal that the nose was

missing long before Napoleon's arrival;

one story goes that it was the victim

of target practice in the Turkish period. Another explanation (and perhaps

the most likely), is that it was pried off

by chisels in the eighth century A.D. by a Sufi who considered the Sphinx a sacrilegious idol. In 1858, some of the sand

around the sculpture was cleared by

Auguste Mariette, the founder of the

Egyptian Antiquities Service, and between 1925 and 1936, French engineer

Emile Baraize excavated the Sphinx on

behalf of the Antiquities Service. Possibly for the first time since antiquity,

the Great Sphinx was once again exposed to the elements.

The Great Sphinx in 1867, in its unrestored original condition,

still partially buried in the sand.

The explanation for the enigmatic

sculpture (favored by most Egyptologists) is that Chephren, a Fourth

Dynasty pharaoh, had the stone

shaped into a lion with his own face at

the same time as the construction of

the nearby Pyramid of Chephren,

around 2540 B.c. However, there are

no inscriptions anywhere that identify

Chephren with the Sphinx, nor is there

mention anywhere of its construction,

which is somewhat puzzling when considering the grandness of the monument. Despite many Egyptologists

claims to the contrary, no one knows

for sure when the Sphinx was built or

by whom. In 1996, a New York detec

tive and expert in identification concluded that the visage of the Great

Sphinx did not match known representations of Chephren's face. He maintained that there was a greater

resemblance to Chephren's elder

brother, Djedefre. The debate is still

continuing. The mystery of the

Sphinx's origin and purpose has often

given rise to mystical interpretations,

such as those of English occultist Paul

Brunton, and, in the 1940s, American

psychic and prophet Edgar Cayce.

While in a trance, Cayce predicted that

a chamber would be discovered underneath the front paws of the Sphinx,

containing a library of records dating

back to the survivors of the destruction of Atlantis.

The Great Sphinx was excavated

from a relatively soft, natural limestone, left over in the quarry used

to build the Pyramids; the forepaws

being separately made from blocks of

limestone. One of the main oddities

about the sculpture is that the head is

out of proportion to its body. It could

be that the head was re-carved several times by subsequent pharaohs since

the first visage was created, though

on stylistic grounds this is unlikely

to have been done after the Old Kingdom period in Egypt (ending around

2181 B.c.). Perhaps the original head

was that of a ram or hawk and was recut into a human shape later. Various

repairs to the damaged head over

thousands of years might have reduced or altered the facial proportions. Any of these explanations could

account for the small size of the head

in relation to the body, particularly if

the Great Sphinx is older than traditionally believed.

There has been lively debate in recent years over the dating of the

monument. Author John Anthony

West first noticed weathering patterns on the Sphinx that were consistent with water erosion rather than

wind and sand erosion. These patterns

seemed peculiar to the Sphinx and

were not found on other structures on

the plateau. West called in geologist

and Boston University professor Robert Schoch, who, after examining the

new findings, agreed that there was

evidence for water erosion. Although

Egypt is arid today, around 10,000

years ago the land was wet and rainy.

Consequently, West and Schoch concluded that in order to have the effects

of water erosion, the Sphinx would

have to be between 7,000 and 10,000

years old. Egyptologist's dismissed

Schoch's theory as highly flawed; pointing out that the once prevalent great

rain storms over Egypt had stopped

long before the Sphinx was built. More

seriously, why were there no other

signs of water erosion found on the

Giza plateau to validate West and

Schoch's theory? The rain could not

have been restricted to this single monument. West and Schoch have also been

criticized for ignoring the high level of

local atmospheric industrial pollution

over the last century, which has severely

damaged the Giza monuments.

Someone else with his own theory

regarding the Sphinx's date is author

Robert Bauval. Bauval published a

paper in 1989 showing that the three

Great Pyramids at Giza-and their

relative position to the Nile-formed

a kind of 3-D hologram on the ground,

of the three stars of Orion's belt and

their relative position to the Milky

Way. Along with best-selling Fingerprints of the Gods author Graham

Hancock, Bauval developed a theory

that the Sphinx, its neighboring pyramids, and various ancient writings,

constitute some sort of astronomical

map connected with the constellation

Orion. Their conclusion is that the best

fit for this hypothetical map is the position of the stars in 10,500 B.c., pushing the origin of the Sphinx even

further back in time. There are various legends of secret passages associated with the Great Sphinx.

Investigations by Florida State University, Waseda University in Japan,

and Boston University, have located

various anomalies in the area around

the monument, although these could

be natural features. In 1995, workers

renovating a nearby parking lot uncovered a series of tunnels and pathways,

two of which plunge further underground close to the Sphinx. Bauval

believes these are contemporaneous

with the Sphinx itself. Between 1991

and 1993, while examining evidence for

erosion at the monument using a seismograph, Anthony West's team found evidence of anomalies in the form of

hollow, regularly shaped spaces or

chambers, a few meters below the

ground, between the paws and at either side of the Sphinx. No further

examination has been allowed. Could

there have been a grain of truth in

Edgar Cayce's library of records prophecy after all?

Today, the great statue is crumbling because of wind, humidity, and

the smog from Cairo. A huge and

costly restoration and preservation

project has been underway since 1950,

but in the early days of this project,

cement was used for repairs, which

was incompatible with the limestone,

and so caused additional damage to the

structure. Over a period of 6 years,

more than 2,000 limestone blocks

were added to the structure, and

chemicals were injected into it, but

the treatment failed. By 1988, the

sphinx's left shoulder was in such a

state of deterioration that blocks

were falling off. At present, restoration is still an ongoing project under

the control of the Supreme Council of

Antiquities, which is making repairs

to the damaged shoulder and attempting to drain away some of the subsoil.

Consequently, today the focus is on

preservation rather than further

explorations or excavations, so we will

have to wait a long time before the

Great Sphinx gives up its secrets.

© Thanassis Vembos.

Ruins of the palace at Knossos, showing some of Arthur Evans's

reconstruction.

The archaeological site of Knossos

is situated on a hill 3.1 miles southeast of the city of Heraklion, the modern capital of the Aegean island of

Crete. Knossos was constructed by the

Bronze Age Minoan civilization,

named for the legendary King Minos

of Crete. The Minoan culture existed

on the island for around 1500 years,

from 2600 to 1100 B.C., and was at its

height from the 18th to 16th centuries

B.C. The main feature of the extraordinary site at Knossos is the Great Palace, a huge complex of rooms, halls, and

courtyards covering approximately

205,278 square feet. The Palace of

Knossos is closely associated in Greek

myth with Theseus, Ariadne, and the

dreaded Minotaur. In fact, the legend

of the labyrinth constructed by

Daedalus to conceal the dreaded manbeast has been understood by some to

originate with the complex layout of

the palace itself. There are even dark

hints in archaeological findings at

Knossos (and elsewhere on Crete) of

the practice of human sacrifice, as is

suggested by the myth of Athens sending 14 girls and boys every seven years

to be devoured by the Minotaur.

The site of Knossos was first discovered in 1878 by Cretan merchant

and antiquarian Minos Kalokairinos,

who excavated a few sections of the

west wing of the palace. But systematic excavations at the site did not begin until 1900, with Sir Arthur Evans,

director of the Ashmolean Museum in

Oxford, who purchased the whole area

of the site and continued his investigations there until 1931. The work of

Evans and his team at Knossos revealed (among other things) the main

palace, a large area of the Minoan

city, and various cemeteries. Evans

carried out much restoration work at

the Palace of Minos, as he called it,

much of it controversial, and the palace in its present form has been said

by some archaeologists to be as much

due to Evans's imagination and preconceptions as to the ancient Minoans.

Since Evans's time, further excavations at Knossos have been undertaken

by the British School of Archaeology

at Athens and the Archaeological Service of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture. The hilltop on which Knossos is

situated has an extremely long history

of human habitation. People were living there from Neolithic times (7000

B.c.-3000 B.C.) continually up until the

Roman period. The name Knossos derives from the Linear B word for the

city: ko-no-so. Linear B is the oldest

surviving example of the Greek language, and was in use on Crete and the

Greek mainland from the 14th to the

13th centuries B.C. Examples of Linear

B script were found at Knossos in the

form of clay tablets, which were used

by palace scribes to record details of

the workings and administration of

their main industries, such as the production of perfumed oil, gold and

bronze vessels, chariots and textiles,

and the distribution of goods such as

wool, sheep, and grain. Clay tablets

inscibed with the earlier undeciphered

Cretan Linear A script were also

found by Evans at Knossos.

The first Minoan Palace was built

on the Knossos site around 2000 B.C.

and lasted until 1700 B.C., when it was

destroyed by a huge earthquake, thus

bringing to an end what is referred to

by archaeologists as the Old Palace

Period. A new, more complex palace

was erected on the ruins of the old; this

structure heralded the Golden Age of

Minoan culture, or the New Palace

Period. This Great Palace, or Palace

of Minos, was the crowning achievement of Minoan culture and the center of the most powerful city state on

Crete. The timber- and stone-built

multi-storied complex acted as an

administrative and religious center,

with perhaps as many as 1,400 rooms.

The plan of the Knossos Palace was

similar to other palaces of this period

on Crete, such as that at Phaistos in

the south-central part of the island,

though Knossos seems to have been

the capital. Minoan palaces generally

consisted of four wings arranged

around a rectangular, central court,

which acted as the heart of the whole

complex. Each section of the Knossos

Palace had a separate function; the

western part contained the shrines,

suites of ceremonial rooms, and narrow storerooms, which were full of

huge storage jars, known as pithoi.

The elaborately decorated Throne

Room complex was also located in

this section of the complex, and had a

stone seat built into the wall facing a

row of benches. This seat was interpreted by Arthur Evans as a royal throne, and the name has stuck. In the

far west of the complex was the great

paved West Court, the formal approach to the palace. The east wing of

the structure once had four levels,

three of which remain today. Located

in this part of the complex were what

have been interpreted as residential

quarters for the Minoan ruling elite,

workshops, a shrine, and one of the

most impressive achievements of

Minoan architecture: the Grand Staircase. Other parts of the Palace include

large apartments with running water

in terracotta pipes, and perhaps the

first example of flush toilets.