Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (6 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

and threatens to flood the site of the

city. There was a catastrophic flood at

Petra in 1963, after which the government decided to construct a dam to

redirect the flood water. During building, the excavators were astonished

to discover that the Nabateans had

already built a dam, probably around

the second century B.C., to redirect the

flood water away from the entrance and

to the north, via an ingenious

system of tunnels, which eventually

diverted the water back into the heart

of the city for the use of the population.

The siq eventually opens out dramatically to reveal the best known and

most impressive of the monuments of

Petra, the classically influenced Treasury (El-Khazneh in Arabic). The name

Treasury originates from a Bedouin

legend that a pharaoh's treasure was

hidden inside a huge stone urn which

stands at the top of the structure. The Bedouins, believing the story,

would periodically fire their rifles at

the urn hoping to break it open and

recover the treasure. The many bullet

holes still visible on the urn are proof

of this practice. The well-preserved

facade of the Treasury, carved out of

the solid sandstone rock, is decorated

with beautiful columns and elaborate

sculptures showing Nabatean deities

and mythological characters, and

stands 131 feet high and about 88 feet

wide. The structure may have served

as a royal tomb, perhaps with the

king's burial place in the small chamber at the back, and also seems to have

been used as a temple, though to

which specific god or gods it was dedicated is not known. The exact date of

the Khazneh is not certain, though construction somewhere in the 1st century B.C. is the most likely.

One of the few remaining freestanding buildings at Petra is the huge

masonry-built Temple of Dushares,

also known mysteriously as Qasr alBint Firaun (The Castle of Pharaoh's

Daughter). This extensively restored

large yellow sandstone temple stands

upon a raised platform and has massive 75 feet high walls. The temple,

built sometime between 30 B.C. and A.D.

40, was dedicated to Dhushares, the

chief god of the Nabateans, and has the

largest facade of any building in Petra.

Inside, the building is separated into

three rooms, the middle room serving

as the sanctuary, or holy of holies.

Facing this structure is the Temple

of the Winged Lions, named after two

eroded lions carved on either side of

the doorway. This structure, the most

important Nabatean temple ever discovered, has been the subject of more

than 20 years of research and excavation by the American Expedition to

Petra. Apparently the temple was

dedicated to the pre-Islamic Arabian

fertility goddess Allat, who was one of

the three chief goddesses of Mecca.

Rather than a single building, the

Temple of the Winged Lions is really

a temple complex including workshops

and living areas. (One of the workshops even manufactured souvenirs!)

The temple is almost certainly the one

described in the Dead Sea Scrolls as

the Temple of Aphrodite at Petra. As

the site has produced such a huge

amount of excavated material the exact dates of its habitation are known.

The temple was founded in August A.D.

28 and was destroyed in the May A.D.

363 earthquake that brought down

many of the city's buildings.

The largest monument in Petra and

one of the most striking is El-Deir (the

Monastery), acquiring the name from

its use as a church during the Byzantine period (c. A.D. 330-A.D.1453). The

spectacularly situated structure, high

up on the mountain, is 164 feet wide

and 148 feet high, with its great doorway measuring around 26 feet in

height. The structure is carved, as

with the Treasury, into the side of a

cliff face. In fact, the Monastery is similar to a larger, rougher, weatherbeaten version of the more famous

Petra monument. Archaeologists believe that construction of El-Deir began during the reign of Nabatean king

Rabel II (A.D. 76-106), but was never

completed.

Petra was brought back to the center of public attention in 1989 with

the release of Indiana Jones and the

Last Crusade, starring Harrison Ford. In the film, it served as a secret

temple hidden for hundreds of years,

and the place where Harrison Ford finally locates the Holy Grail. It was in

the news again in 2005, when the Dalai

Lama led a host of Nobel Prize winners who, together with actor Richard

Gere, organized a two-day conference

at the rose red city entitled "A World

in Danger." The fortunately excellent

state of preservation of much of the

ancient city can be explained by the

fact that most of its structures have

been carved out of solid rock. However,

as with many ancient monuments, the

sandstone buildings at Petra are in

constant danger from excessive tourism, and the free-standing buildings in

particular are suffering from salt, water, and wind erosion. On December

6, 1985, Petra was recognized as a

World Heritage Site by UNESCO (the

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization), and

for the past few years conservationists

have been at work on the monument

filling in the holes and cracks in the

stone with a specially designed mixture, as close as possible to the original sandstone of the 2,000-year-old

plus structures. Hopefully, one of the

world's most beautiful and spectacular ruined cities will be around for at

least another 2,000 years.

© Thanassis Vembos.

The Monastery at Petra.

Photograph by the author.

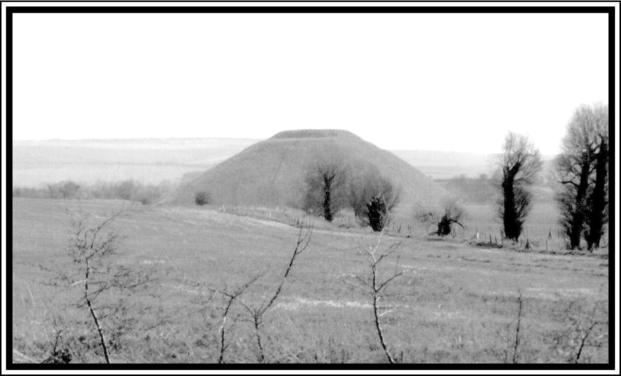

Silbury Hill, barely reaching the height of the surrounding hills.

Lying low in the Kennet valley in

Wiltshire, southern England, looms

the mysterious Silbury Hill, the largest man-made mound in Europe and

one of the biggest in the world. The

site stands amid the prehistoric sacred

landscape surrounding the present

day village of Avebury, and contains a

complex of Neolithic monuments, including an enormous henge (a roughly

circular flat area enclosed by a boundary earthwork), stone circles, stone

alignments, and burial chambers. The

imposing earthwork structure of

Silbury Hill stands at 128 feet high, its

flattened top is 98 feet across, and its

diameter at the base is 547 feet. The

huge 125 foot wide ditch that surrounds

Silbury was the source of much of the

material which makes up the mound,

an amazing 8,756,880 cubic feet of

chalk and soil. It has been estimated

that construction of the monument

would have taken the efforts of 1,500

to 2,000 men working for a year, 300

to 400 men working for more than five

years, or 60 to 80 men working for

more than 25 years. In all, an estimated 4 to 6 million man hours, though

some have suggested a figure as high

as 18 million hours. Because of its dimensions, Silbury has often been compared with the Great Pyramid in

Egypt, which is roughly contemporary with the huge English earthwork. According to a radiocarbon date recently

obtained from an antler pick fragment,

Silbury probably achieved its final

form between 2490 B.C. and 2340 B.C.

But what was the purpose of such a

massive undertaking of organization

and manpower?

There is at present no consensus

of opinion amongst archaeologists as

to how many building phases there

were at the huge earthwork at Silbury,

though we know its builders used tools

of stone, bone, wood, and antler in its

construction. The late Richard

Atkinson, who excavated the mound in

the late 1960s, hypothesized three

separate phases. In the first of

Atkinson's phases (Silbury I), dated to

around 2700 B.C., the earthwork consisted of a low gravel-built mound covered in alternating layers of chalk

rubble and turf, around 18 feet high

and about 115 feet across. Atkinson

believed that Silbury II was begun

about 200 years later, and consisted of

a much larger mound constructed over

the top of Silbury I. In this phase, the

earthwork had a diameter at its base

of about 246 feet, with a height of 66

feet. Silbury III was the hill's final

form, basically the earthwork we see

today. Atkinson thought that the structure of Silbury III had been built up in

tiers of chalk, only the upper two of

which are now visible on the monument. Each of these horizontal steps

was inclined inwards at an angle of 60

degrees, to provide the monument

with stability; the tiers were then

filled in with soil, probably from the

ditch at the base of the mound. Despite

Atkinson's three-phase theory, the latest evidence from surveys of parts of

Silbury has revealed the possibility of

there being only one construction

phase at the site. Only a complete survey of the whole monument will decide

this issue.

There have been three main excavations undertaken at Silbury Hill in

an attempt to fathom its mystery. The

first of these was carried out by the

Duke of Northumberland in 1776, who

hired a team of Cornish miners to dig

down from the top of the mound. However, they found nothing of note, and

as the workers did not fill in the shaft

properly after investigations were finished, their excavation led ultimately

to the partial collapse of the summit

of the mound in 2000. Antiquarian

Dean Merewether supervised the excavation of a tunnel from the side of

the hill to its core in 1849, but this shed

little light on the function of Silbury

Hill. Professor Richard Atkinson's

BBC-sponsored excavations of the

enigmatic earthwork, which took place

from 1968 to 1970, have been the most

comprehensive investigations of the

site to date. One of Atkinson's three

trenches followed Merewether's tunnel, but there were no sensational

finds. In fact, precious few artifacts at

all, no burials, and no clues to the function of the structure were found. However, from his work at the site,

Atkinson was able to arrive at his

theory about how the mound had been

constructed. Atkinson's excavations

also revealed considerable environmental evidence, including the presence of flying ants in the turf of

the building, which has been used

to suggest that construction of the

earthwork was begun in the month of

August, interpreted by some as coinciding with the Celtic Festival of

Lughnasadh, or Lammas. Even though Silbury was constructed 2,000 years

before, there is evidence of Celtic

culture in Britain.

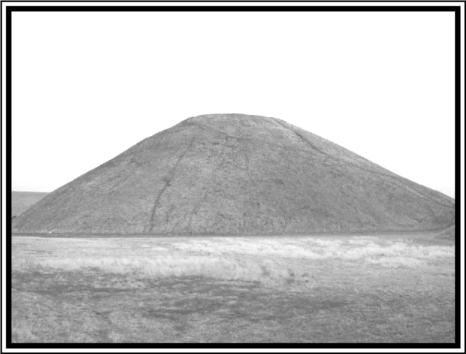

Close-up of the mysterious Silbury Hill.

Photo by the author.