Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (3 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Unfortunately, evidence for a pet

theory is usually obtained by ignoring

conflicting data, or taking an individual artifact, person, or even place

out of its original context. Let's imagine a situation where, for example, you

wanted to prove that Ireland had been

invaded by the Romans, even though

the vast majority of archaeologists and

historians are convinced it never was.

There are a fair amount of Roman finds

in the country, some from sealed archaeological contexts, which you could

use to support your case. But if these

Roman objects are looked at in greater

detail and their original contexts examined, then it becomes apparent that

the artifacts are of the portable variety: pottery, coins, and jewelry. Roman

objects in Ireland are usually found at

religious sites, such as the huge burial

mound at Newgrange, north of Dublin,

which were already thousands of years

old by the Roman period. This would

indicate that, rather than signifying a Roman invasion, the objects were the

result of religious offerings by pilgrims, probably visiting from Britain.

A cursory glance at the artifacts in isolation could never have arrived at this

conclusion.

Of course, one must always be careful to distinguish between genuine and

spurious mysteries, and for this reason a few puzzles of the spurious category have been included in this book.

It is surprising how many apparently

inexplicable mysteries (especially

those relating to unusual objects) prove

on closer examination to have prosaic

explanations. With the proliferation of

Websites dedicated to ancient mysteries, secret societies, and out-of-place

artifacts, stories are fabricated entirely

on the Internet, without any supporting evidence or research, and are reproduced uncritically as fact. One of the

best examples of these "Internet

truths" is the supposedly ancient Coso

Artifact, a short chapter on which is

included in this book. A major problem

with many of the speculations that surround unexplained ancient artifacts is

that the objects are taken out of their

original context in order to provide

evidence for a favorite theory. Just

because the peoples of prehistoric

Britain and ancient Peru carved figures into the landscape doesn't mean

there was any contact between the two

places. What it does signify is a basic

human need to express oneself using

the landscape, of which the people

perhaps believed themselves to be a

part. The lives of many of the cultures

of antiquity were full of magic and

mystery, but to acquire even a partial

understanding of this often entails

cutting oneself off from present-day

preoccupations and desires. If this is

not done, then we are in danger of

clothing the ancient peoples of the

world in modern, ill-fitting garments,

and transforming them into 21st century ancients who would not have been

recognized in their original cultures.

On the other hand, to deny the

mysteries of the past completely, to

believe that modern archaeology and

science have the answers to every ancient enigma, is equally ill-advised. (It

also makes dull reading.) Alternative

theorists, such as Graham Hancock,

Robert Bauval, and Christopher

Knight may sometimes be too uncritical when dealing with the evidence for

lost civilizations and ancient technology, but they are better writers than

most archaeologists. Academics are

never going to convey the fascination

of their subject to the general public if

their commercial publications read

like technical reports, or notes written for a lecture to a group of Ph.D.

students. There are, of course, exceptions: Mike Pitts's Hengeworld,

Francis Pryor's Britain BC, and Barry

Cunliffe's Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC to AD 1500,

should be read by everyone with an

interest in ancient history.

In Hidden History, ancient mysteries are divided into three categories:

Mysterious Places, Strange Artifacts,

and Enigmatic People. The choice of

subjects included in the book was a

personal one, made to bring together

the most interesting of ancient mysteries, and to cover a wide range of

cultures, time periods, and types of

mystery. The book has no hidden

agenda; I hope my readers will use the

evidence presented to make up their

own minds about these riddles of our

enigmatic past.

Places

Blank Page

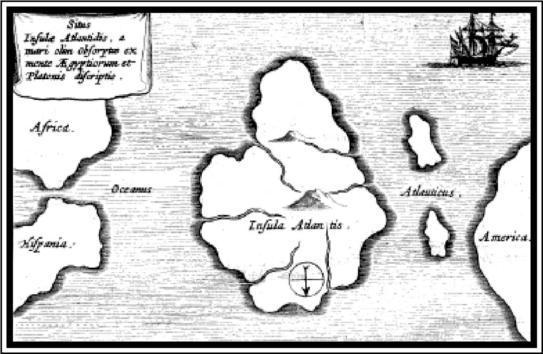

Athanasius Kircher's map of Atlantis's possible location.

From Mundus Subterraneus (1669).

The magical lost land of Atlantis

has captured the imagination of poets,

scholars, archaeologists, geologists,

occultists, and travelers for more than

2,000 years. The notion of a highly

advanced island civilization (that

flourished in remote antiquity only to

be destroyed overnight by a huge

natural catastrophe) has inspired believers in the historical truth of the

Atlantis tale to search practically every corner of the Earth for remnants

of this once great civilization. Most archaeologists are of the opinion that

the Atlantis story is just that, a story,

an allegorical tale with no historical

value whatsoever. And then there

are the occultists, many of whom have

approached the story of Atlantis from

the standpoint that it represents either a lost spiritual homeland (such as

Mu/Lemuria), or a different plain of

existence entirely. What is it about

Atlantis that has inspired such diverse

interpretations? Could there be any

truth behind the story?

The original source from which all

information about Atlantis ultimately

derives is the Greek philosopher

Plato, in his two short dialogues

Timaeus and Critias, written somewhere between 359 and 347 B.C. Plato's

supposed source for the story of

Atlantis was a distant relative of his,

a famous Athenian lawmaker and

Lyric poet named Solon. Solon had, in turn, heard the story while visiting

the court of Amasis, king of ancient

Egypt from 569 to 525 B.C., in the city

of Sais, on the western edge of the Nile

Delta. While at the court of Amasis,

Solon visited the Temple of Neith and

fell into conversation with a priest

who related the story of Atlantis to

him. The priest described a great island, larger than Libya and Asia combined, that had existed 9,000 years

before their time, beyond the Pillars

of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar) in

the Atlantic Ocean. Atlantis was rule

over by an alliance of kings descended

from Poseidon, god of the sea and

earthquakes, whose eldest son, Atlas,

gave his name to the island and the

surrounding ocean.

The Atlanteans possessed an empire that stretched from the Atlantic

into the Mediterranean as far as Egypt

in the south and Italy in the north.

During an attempt to extend their

empire further into the Mediterranean, the Atlanteans came up against

the combined powers of Europe, led by

the city-state of Athens. In this remote

time, Athens was already a great city

and a society ruled by a warrior-elite

class who disdained riches and lived a

spartan lifestyle. The armies of

Atlantis were eventually defeated by

the Athenians alone, after their allies

deserted them. However, soon after the

victory there was a devastating earthquake followed by huge floods, and the

continent of Atlantis sank beneath the

Ocean "in a single dreadful day and

night," in the words of Plato.

The destruction of Atlantis and its

location beyond the Strait of Gibraltar

takes up only a few lines in Plato's

Dialogues, in contrast to his much

more detailed description of the

island's physical and political organization. Initially Atlantis had been an

idyllic place, endowed with a wealth

of natural resources; there were forests, fruits, wild animals (including

elephants), and abundant metal ores.

Each king on the island possessed his

own royal city over which he was complete master. However, the capital

city, ruled by the descendents of

Atlas, was by far the most spectacular. This ancient metropolis was surrounded by three concentric rings of

water, separated by strips of land on

which defensive walls were constructed. Each of these walls was encased in different metals, the outer

wall in bronze, the next in tin, and the

inner wall "flashed with the red light

of orichalcum," an unknown metal. The

Atlanteans dug a huge subterranean

channel through the circular moats,

which connected the central palace

with the sea. They also carved a harbor from the rock walls of the outer

moat. The main Temple of Poseidon,

on the central citadel, was three times

larger than the Parthenon in Athens,

and was covered entirely in silver

(with the exception of the pinnacles,

which were coated in gold). Inside the

temple, the roof was covered with

ivory and decorated with gold, silver,

and orichalcum; this strange metal also

covered the walls, pillars, and floor of

the temple. The temple interior also

contained numerous gold statues, including one of Poseidon in a chariot

driving six winged horses, which was

of such a colossal size that the god's

head touched the roof of the 381 foot

high ceiling.

All other ancient sources for the lost

continent of Atlantis are subsequent to

Plato, and at best provide tantalizing glimpses of what the people antiquity really believed about Atlantis.

In the fourth century B.C. the Greek

Philosopher and student of Aristotle,

Theophrastus of Lesbos, mentioned

colonies of Atlantis, but unfortunately

the bulk of his work has been lost.

In his commentaries on Plato's dialogues, Proclus, writing in the fifth

century A.D., commented on the reality of Atlantis, stating that the

Atlanteans "for many ages had reigned

over all islands in the Atlantic sea."

Proclus also tells us that Crantor, the

first commentator on the works of

Plato in the fourth century B.C., had

visited Sais in Egypt and had seen a

golden pillar with hieroglyphs recording the history of Atlantis. Claudius

Aelianus, a second century A.D. Roman

writer, mentions Atlantis in his work

On the Nature of Animals, describing

a huge island out in the Atlantic Ocean,

which was known in the traditions of

the Phoenicians (and sebsequently the

Carthaginians of Cadiz), as an ancient

city on the coast of southwest Spain.

American congressman and

author Ignatius Donnelly.