Hieroglyphs (17 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

One of his jobs was to look after the funerary cult of a vizier of Montuhotep II, called Ipi. This meant taking care of an area of land which would be cultivated to provide both the offerings for the cult and the payment in kind for Hekanakht. This man clearly had other irons in the fire, though, and his business interests sometimes took him away from home. At times like this, he sent back a stream of letters to his deputy and eldest son, Merisu, to make sure his household and his interests were being looked after. It seems likely that though he did write some of the letters by himself he also dictated others to a scribe, either because he was too busy to sit down and write them or because he had never had formal training or because his status allowed him to have a secretary. The style is

phs

very colloquial and, even in translation, he can be imagined pacing

ogly

up and down, barking out thoughts and random sentences to the

Hier

scribe trying to keep up with him. At one moment he is concerned that people are working hard for him; at another that everyone in his household is getting their fair rations; and then he is worried that his concubine is not being treated well by his sons and daughters. So vivid were his outpourings that Agatha Christie used them as the basis of a murder mystery set in Ancient Egypt (

Death

Comes as the End

). This man’s thoughts and feelings were preserved by a diligent scribe in hieratic for us to read and to enable us to look in on his life. The letters are not always very clear because only one side of the correspondence has survived, but they give much incidental information about the makeup of his household and his dependants and servants, including grown-up and young children, a widowed or unmarried sister, and a second, younger, wife who is the source of friction in the household. One of the letters was addressed to a neighbour and was found unopened, never having been forwarded by Merisu.

4

78

The scribal profession

Scribes were an important part of every businessman’s entourage.

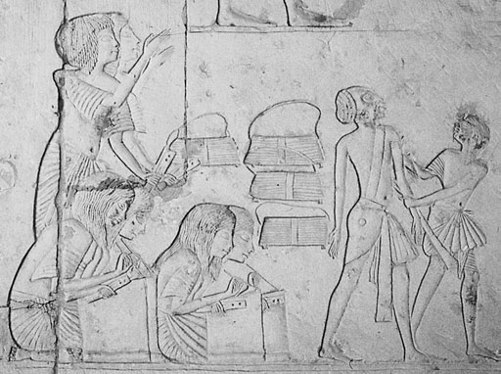

Important facts and figures could not be left to the memory like tales, but a good secretary taking copious notes must have given a sense of security in the face of the administration to people like Hekanakht. The line of scribes in the Tomb of Horemhab are shown wearing their elegant wigs and gowns, each one’s long graceful fingers holding a pen poised above a papyrus. Their almost effete attitude contrasts uncomfortably with the African slave being punched in the face as he is dragged forward to be counted and become a statistic in an account of slaves. The four scribes shown here are presumably recording the accounts in quadruplicate.

There is no doubt, however, that scribes prided themselves on their

Scribes an

skill and their ability. In a fictional literary teaching, a pompous scribe called Hori scolds a colleague and exhorts him to acquire

d e

the skills to organize the excavation of a lake and the building of a

veryda

y writin

g

16. Scribes from the Tomb of Horemhab, Saqqara, Dynasty 18.

79

brick ramp, to establish the number of men needed to transport an obelisk and to arrange the provisioning of a military mission. He is expected to acquire a knowledge of Asiatic geography.

5 A series of

texts written by scribes for scribes and called the ‘Satire of the Trades’ poked fun at a variety of manual workmen, including the potter, the fisherman, the laundry man, and the soldier doing service overseas far from home. The sections end with the exhortation, ‘Be a Scribe’, and it is clear that the virtues of clean living, wearing fine linen, and living a rarefied, easier life were much to be admired.

The tenor of the Satire is that the scribal trade is the best and is the way to get on in life. It is assumed that everyone who wanted some sort of administrative post in one of the main divisions of the state bureaucracy essentially started learning to read and write together.

Literacy was essential for all élite offices for men. Most elder sons followed in their father’s footsteps, but there were also people who

phs

had risen through the ranks and sent their sons to school in order to

ogly

ensure their status. How many people of natural ability were

Hier

harvested along the way and given a scribal training is not known.

After initial training in hieratic, men were selected to serve in one particular branch of administration. They worked as accountants in the financial institutions of state or as legal clerks in the legal administration. In temples, scribes could be priests, copying out sacred texts or performing the rituals there, or they may have had administrative duties in running the temple estates and storehouses. The army had many military scribes, keeping daily records of campaigns and accounts of supplies to the expeditionary forces. At court, scribes were responsible for everything from liaising between various departments to the construction of the king’s pyramid, from negotiating a bride price for a foreign princess to setting the quotas of linen to be produced in the ‘harim’

institution. Each of these areas has a strong bias towards accounting and record-keeping, but each also has a specialist side.

This meant that scribes were interchangeable (having transferable skills) and could move through the bureaucracy. It is no accident 80

that some of the most powerful men in Egypt, such as the vizier, Paser, the general, Horemhab, and the priest, Herihor, had served in several offices and could convert their experience of how the state worked into royal power.

The initial training for scribes began in boyhood. Those chosen were lined up in rows, sitting with their texts on their kilts, and they chanted texts learned by heart until they could fit together hieroglyphs, words, and grammatical constructions and then read whole texts. In the New Kingdom they also copied out older, classic, set texts, including the Story of Sinuhe, which was evidently about what it was to be Egyptian, but more popular were the ‘Satire of the Trades’, ‘Instruction of Amenemhet I’, and ‘Kemyt’ (a compendium of model letters).

6

All texts serve the dual purpose of teaching the mechanics of reading and writing, as well as inculcating proper

Scribes an

behaviour within the scribal and administrative profession and setting out the code of ethics for scribes. Trainee scribes who did not

d e

work hard enough were beaten on the back and those who drank

veryda

too much beer and visited whorehouses were not considered to be

y writin

good examples of the profession.

g

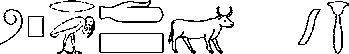

It is likely that all scribes learned hieratic, but only those who became draughtsmen or priests learned hieroglyphs. The recognizable training texts which have survived are mostly in hieratic and clearly this was the most useful script to learn. Very few learning aids such as dictionaries have survived from Egypt, perhaps because of over use, but some word lists and an occasional grammatical paradigm do exist. The Tanis Sign Papyrus has columns for: a hieroglyph, the hieratic equivalent, then a brief note in hieratic of what the sign is; for example,

is described as

‘mouth of a human being’. The Geographical Papyrus also found in a charred mass in a house at Tanis has information in hieroglyphs about each administrative area of Egypt (nome): the name of a nome capital, its sacred barque, its sacred tree, its cemetery, the date of its festival, the names of forbidden objects, the local god, land, and lake of the city. This interesting codification of data, 81

probably made by a priest, is paralleled by very similar editions of data on the temple walls at Edfu, for e

xample.7

The arrangements of the word lists (‘Onomastica’) are interesting because they suggest the way in which the Egyptians thought about their language and also their world. The Onomasticon of Amenemope is divided into sections of groups of words which refer to the same idea: words for sky, water, and earth; administrative titles and occupations; classes, tribes, and types of human beings; towns of Egypt; buildings and types of land; agricultural land, cereals, and products; beverages and parts of cattle and cuts of meat. If these were used as teaching aids for spelling or for administrative and tax reference, the ‘standard’ terms would then have been consistently used by scribes throughout Egypt and seem to reflect the usual pragmatic approach of the Egyptians. The New Kingdom examples of such texts seem very clumsy, though, as the words are simply written in horizontal lines following one from

phs

another, collecting all the information together in one place. It must

ogly

have been difficult to find the word you needed. It seems that by this

Hier

time the texts were being copied and perhaps were intended as back-up copies, with scribes memorizing appropriate chunks. The Middle Kingdom Ramesseum Onomasticon is much more useful as it is set out in columns and each entry can be clearly seen. It contains, for example, a list of cattle markings showing the particular sign which was to be used for a particular type of bull:

‘the wadj-sign : it is a red-bull’.

8

The surviving medical texts have a similar function. They contain a description of the problem, the diagnosis of the disease or injury, and a prognosis and prescription. They sometimes also back up the practical advice with magical spells against evils and on behalf of the sick person. These texts have been described as ‘magic’ based on superstition, but they may have had a valuable psychosomatic effect, in much the same way as modern placebo medicines. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus is an exemplary set of mathematical 82

exercises, giving various problems, such as calculating the volume of a cylindrical grain store or the slope of a ramp – essential knowledge in pyramid-building – and then working through them, so that a scribe can follow all the steps of the process and practise it himself.

The calculations required the manipulation of fractions which demonstrate a love of numbers for their own sake, but nonetheless with very prac

tical applications.9

There are scribes who were recognized for their skill and wisdom while still alive as well as some even venerated after their death.

A man named Bakhenkhons, who lived during the reign of Ramesses II, left behind a summary of his life on a statue dedicated in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. He had been the First Priest of Amun and a town governor, but on his statue he addresses us directly: ‘I shall have you know what my achievement was when

Scribes an

I was upon earth and every rank which I held since my birth: I spent 4 years as an excellent youngster, I spent 11 years as a youth

d e

when I was the chief of the training stables of King Menmaatre.

veryda

I spent 4 years as a waab-priest of Amun, 12 years as the ‘‘God’s

y writin

Father of Amun’’, 15 years as the Third Priest of Amun, 12 years as the Second Priest of Amun and then 27 years as the First Priest of

g