High Price (17 page)

Authors: Carl Hart

“Yo, you down?”

“You know I’m down.”

“I’m down,” everyone else would say.

“Cool,” we’d agree, and then pile into two cars and roll to the white section of town as if no one would notice us. I’d always stay in the car. If we’d been busted, I now realize, I’d have been considered the lookout, but I didn’t think of it that way. Sometimes, I was just trying to get a ride home. Other times, I’d get a share of the loot, like a camera that was smaller than my hand, which was probably extremely expensive back then.

I always tried to be alert to the potential risks as well as the benefits of the crimes I committed. Though it may have looked like teen impulsiveness (and, of course, I did have the adolescent cockiness that creates risk-blindness—pointing the gun at that white man wasn’t exactly a smart move), I wasn’t usually stupid, either. I wouldn’t do things that I’d seen people catch a case for; I wouldn’t risk shoplifting at that mall filled with cameras and security guards and I wouldn’t do anything violent like mugging people. My goal was to stay in school so I could become a professional athlete.

Once, while the guys were burglarizing someone’s home, they had to fight off some girls who came back unexpectedly and caught them. But fortunately, that was the closest I ever got to getting into trouble with those guys. We laughed it off, not even thinking how our behavior might have affected those girls. In fact, we mercilessly teased Larry, who had punched one of them while trying to get her purse. He’d hit her so lightly she didn’t even drop the bag—and then he’d had to run to the car before we drove off without him.

As with my earlier lawbreaking, these activities had nothing to do with drugs and everything to do with street credibility. Even as I participated in burglaries and stole batteries, I also worked whatever job I had. I diligently showed up when required and always did what needed to be done, not seeing any contradictions in my behavior. I worked hard because you were supposed to work hard; I stole because there was never enough money; I went to school so I could get a basketball scholarship. At sixteen, I still thought I was going to play in the NBA, though earlier, the dream had been the NFL. The main career plans I ever had as a kid were these hazy visions of becoming a professional athlete. Fortunately, they had the side effect of keeping me in school.

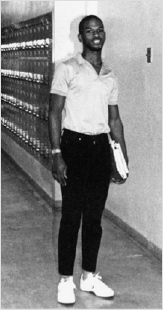

Standing in the hallway at Miramar High School during my senior year.

I also felt justified taking from those we viewed as having excess, like we were Robin Hood. My highest paid job in high school barely earned me four dollars an hour. (Though the older guys made money from deejaying, I was just glad to be up front and part of that scene with my brothers-in-law. I got my money elsewhere.) When I later learned about psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, I felt vindicated. I’d reached the “highest” level of moral thinking, according to him, in early childhood: I’d gone from thinking that rules alone determined what was moral to thinking about universal principles of justice, before I’d hit my teens.

It had always seemed obvious to me that if, say, your family needed a lifesaving drug, it would not be immoral to steal it. What kind of person would let arbitrary rules that let rich people have access and let poor people die stop him if he had a choice? I didn’t understand why everyone wouldn’t see the situation as unjust if property was more valued than life.

During my senior year, Derrick Abel and I plotted with a guy we knew who transported money from a local movie theater to the bank. We were going to rob him but not hurt him; he was, in fact, our inside man. The runner, we were told, carried thousands of dollars. It would be our biggest heist ever. We talked and talked about it. Our friend Alex, however, refused to get involved. He was about five foot eleven, with a small mustache and muscular build. I’d always thought he was cool. But he said, “Fuck that shit. That’s stupid.” To my shock, he flat out said no.

Thinking back later, I realized he was from a two-parent family and had had a lot more guidance than I did. At the time, though, we decided at that instant that he was uncool. Fuck him, we’re no longer friends. We dropped him without further thought for a few weeks; someone that punked out couldn’t be down with us; he couldn’t be trusted. I didn’t see this as cold or callous; that was just how it was.

In fact, it boggled my mind that someone would ever say no to his boys; for me, cool and its requirement of loyalty to our group always came first. It was the foundation of my values, one of the few things that really meant something to me and structured my social life. Putting those ties at risk, to me, seemed much more dangerous and threatening than anything the system could do to you if you ever did get caught. If you stayed cool, you could handle that. If not, you weren’t a man and there was nothing much to live for anyway. As it happened, we never got around to robbing the guy. I reinstated my friendship with Alex about a month later. But I never shared information about my capers with him again because I knew he wouldn’t be interested in participating.

Episodes like my narrow escape from the battery store and our somewhat arbitrary decision not to do the movie payroll job pose deep questions about the role of luck and chance in a person’s life. If we’d gone ahead with that risky plan or if I had gotten caught and punished for some of my other activities the way so many of my friends eventually did, many of the opportunities that I have had would almost certainly have been lost to me. It wasn’t that I didn’t do the foolish things that other kids around me did; it was that I didn’t get caught doing them. Like Presidents Obama, Clinton, and George W. Bush, some of my fate rested on not getting caught taking drugs or engaging in other “young and irresponsible” activities.

As a scientist, I’m familiar with Louis Pasteur’s notion that “chance favors only the prepared mind”—the idea that while luck does play some part in great discoveries, hard work prepares the soil without which they cannot grow. The same is true in my life. Without a lot of hard work, I’d never have gotten to be where I am. Unlike luck, hard work is under your control: you can either do it or you can take shortcuts. That’s quite clear and often differentiates between winners and losers. I believe deeply in putting in the effort and tell my children so ad nauseam.

But I’m also acutely aware that often, hard work isn’t enough, especially when the stupid things that black children do are punished much more severely and with much more lasting negative effects than happens with the equally stupid things that white children do. Of course, I’m not arguing that crimes like robbery and burglary shouldn’t have consequences. They should. I just think that the consequences should both be educational and allow for redemption.

And data shows us that the criminal justice system is not the best way to impose these consequences. Its personnel aren’t trained as educators or counselors; they’re trained to contain damage and dole out punishment. Besides this, prisons are difficult to run in a way that keeps children safe and healthy and they are far more expensive to operate than alternatives that are actually more effective. It’s not just my experience—or that of our last three presidents—that suggests that avoiding the justice system produces better outcomes. This is clear from multiple studies.

This data shows that teens who are either not caught or are given noncustodial sentences for their crimes do much better in terms of employment, education, and reduced recidivism than those who are incarcerated or otherwise removed from the community and grouped with criminals.

One large American study examined the cases of nearly one hundred thousand teens who had their first contact with the juvenile justice system between 1990 and 2005. Fifty-seven percent of these youths were black; the overwhelming majority were male and their average age was fifteen. Most had been arrested either for drug crimes or for assault; all were studied at the time of their first offense.

The researchers found that, regardless of the severity of the initial offense, teens who were incarcerated were three times more likely to be reincarcerated as adults

1

compared with those not incarcerated for similar offenses. Being locked up hadn’t deterred them; rather, it had forced them to spend time with criminals, had possibly taught them more about how to commit different types of crime, and ultimately set them up to be reincarcerated.

Similarly, Canadian researchers conducted a large-scale, carefully controlled study in which 779 low-income youth in Montreal were followed from ages ten to seventeen; they were interviewed as well as their parents and teachers. Years later, researchers examined their criminal records and found that those who had received any kind of custodial sentence as teens were thirty-seven times more likely to be arrested in adulthood than their peers who had committed similar crimes but were not incarcerated during adolescence.

2

The data from the above studies and others clearly shows that segregating troubled teens together in settings where there are no parents and few peers aiming for athletic or academic success tends to make their criminal behavior worse.

3

Both being labeled as a “bad kid” and hanging out with peers who feel that their only source of manhood and identity is engaging in criminal behavior significantly increase risk for future crime. Social influences like incarceration during youth predict adult crime far more strongly than anything we’ve been able to identify so far related to biological factors like dopamine in the brain.

Moreover, because black youth are more than twice as likely to be arrested as whites,

4

the negative effects of juvenile prison have a disproportionate effect on our community. (For drug offenses, the inequities are even more glaring: drug cases are filed against black youth at a rate almost five times greater than for white youth, even though more white youth, 17 percent, report having sold drugs than blacks do, 13 percent.)

5

While these facts are discouraging because they show how big the problem is, they also suggest that a clear solution is minimizing juvenile incarceration rates.

The lives of my friends, neighbors, and relatives showed this contrast clearly. Those who managed to avoid contact with the system, as I was, were much more likely to make it out of the hood and into the mainstream. Meanwhile, many of those who got caught never recovered, even if the first offense was truly minor. That one incident would lead to increased scrutiny and then further arrests—or the exposure to juvenile detention or other incarceration would harden a criminal identity and/or connect people to those involved in more serious crime. It was as though a pebble had set off a rock slide. A small event produced a chain of devastating consequences, forever altering a life course.

One of the saddest examples of this in my life is the story of my cousin Louie. The math whiz pitcher with whom I’d shared a bed at Big Mama’s had been an honors student when his mother switched him from one high school to another. Once he got there, the small, skinny kid felt that he had to prove he was down with a new set of friends.

Shortly after his school transfer, Louie was picked up by the police for truancy or some other trivial, nonviolent offense. For that he was sent to juvenile detention at fifteen; the few months he spent inside hardened him and gave him the reputation he’d been seeking, rather than serving as any kind of deterrent. Having survived being locked up, he saw himself as one bad dude. Rather than returning to his advanced math classes, he skipped more and more school and started hanging out with the professional thugs. Soon he dropped out entirely.

By then he was pulling armed robberies, jacking trucks carrying radios, TVs, and other electronics and appliances. He and his friends once hit a Brinks truck and successfully hid the money so well that it has yet to be found. But the rumors about that heist marked the peak of his glory. In his mid- to late teens, he began drinking heavily and smoking weed, and by his early twenties, he’d started smoking crack. He ultimately spent at least ten years in prison—and now lives in a halfway house, barely able to function on the psychiatric medication he was prescribed when he entered prison. Although the details are unclear, it is said that the medications were originally prescribed to control his anger.

Fortunately, there are also positive life events that can lead to spiraling virtuous circles, not escalating vicious ones. For me, one of these was my decision to take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). Although I’d worked relentlessly at athletics and had big dreams about college basketball and the NBA, I’d otherwise given little thought to what I’d do after high school. Since I’d told all my friends that I’d be getting a big college scholarship, I knew I had to leave home somehow—or risk losing the rep I’d so assiduously worked to build up.

I knew nothing about how college basketball really worked and the importance of coaches in getting scholarships for their players. I was ignorant of the machinations and realities of that world. All I did recognize was that without a full scholarship, I probably couldn’t afford to go to college. I needed other options. I wasn’t likely to get much financial support from my mother. In fact, I figured she’d probably pressure me to stay home and work rather than encouraging further education. In our family—as in many others in my neighborhood—children were expected to support, or at least partially support, their parents once they reached working age.