High Price (18 page)

Authors: Carl Hart

My father wasn’t going to be of much use, either. He’d never demonstrated that he had that kind of money to spend on his children. Although I sometimes saw him around, by this time we had drifted apart as fathers and sons often do during adolescence. The thought of having to depend on my mom for college funds or the notion of skipping college—and the chance of a basketball career it offered—and going to work full-time was not appealing to me.

Maybe these considerations were in the back of my mind; maybe they had nothing to do with my decision to take the armed forces test. All I remember is that early in my senior year of high school, I decided to take the ASVAB because it meant that I didn’t have to go to my classes that day. I know for sure that I had no active desire to join the military. The guys I’d seen coming back after they’d joined the army or the Marines seemed brainwashed, no longer concerned with what we cared about and valued. But my guidance counselor, Ms. Robinson, had said I could leave school early if I took the test—and I knew I could bubble in the answers quickly and be on my way to hang out with my friends much faster than I could be if I went to class. That nearly random choice had a considerable influence on my life.

In the school cafeteria, faced with a number-two pencil and a question booklet, my primary goal was to get done quickly. I didn’t fill in the little ovals at random, however. That seemed dumb, even though I told myself that I didn’t care about my score. I did guess without much thought or leave questions blank if something didn’t come to me easily, particularly on the reading and vocabulary sections.

When I got to the math section, however, I found myself paying real attention. I had my pride. I thought to myself, you might trip me up with English or social studies but not math. I did my best on the math sections of the exam. Then I turned it in and forgot about it in my daily routine of basketball, spending nights with my girlfriends, and rocking the mic on the weekends. I didn’t give it another thought.

A few months later, the results came back. To my complete astonishment, I was told that I was one of the only people in my high school to score high enough to be recruited by the air force. At the time, it filled me with pride. Now, however, I don’t think that this shows that I was especially smart: the college-bound kids didn’t take the ASVAB and I suspect I wasn’t the only one who’d simply taken it to get out of class. The scores would have been much higher if the whole class had been required to take it—or if only the college-bound students did so. It didn’t represent a true picture of the smartest kids in the school.

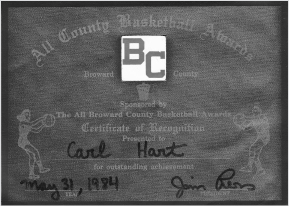

Despite receiving all-county basketball recognition, I didn’t receive a basketball scholarship. As a result, the military became a more likely option.

Today, I’d call that a sampling bias. For example, in my research, I have to think about not just the drug I might be studying but also the kinds of people who would be available for study participation and whether they fairly represent the people I’m trying to understand. While I explore their subjective experiences with them, I also study their behavior on different days and with different doses of drugs. These contextual factors matter a lot: under one condition, I might find one effect but under another, I might find the opposite outcome or no effect at all.

I often explain it this way: Imagine if the only experience you had of driving was being plunked down behind the wheel for the first time in your life in a raging thunderstorm or blizzard on a busy highway. You’d probably think driving was seriously dangerous and that most people couldn’t handle it. You might generalize from your own single experience, under those awful conditions, to that of everyone and see driving a car as something that should be highly restricted.

Of course, your sample of driving in that kind of situation is limited to one sample of an extreme situation. It doesn’t include driving on a bright sunny day, driving once you’ve had years of experience, or driving on a quiet country road. Similarly, using a drug once or twice or seeing a friend become really paranoid as a result of that drug does not provide an adequate sample of the range of possible drug experiences. Likewise, sampling only the non-college-bound students’ results on a test of intelligence does not provide a representative sample of possible test scores for a particular high school class.

But learning to think about ways to really isolate the causes and effects of things was one result of that rather random choice I made to take that test. It eventually opened up a whole new world to me. If I hadn’t made that one, seemingly irrelevant decision to take the ASVAB, it’s unlikely that I would now be a scientist and college professor.

Once those results were in, however, both the army and the air force did a full-court press to try to recruit me. At first, I didn’t really take it seriously. My guidance counselor nonetheless insisted I meet with both recruiters. She set up the meetings in her office and got me out of class for them, once again successfully ensuring my attendance by understanding what motivated me. Although I either acted like a clown or literally slept through many of my classes, Ms. Robinson found me charming and didn’t give up on me, knowing that the military was one of the few options that could make a real difference in my life. Her exceptional dedication to trying to secure a future for me really mattered.

I continued to be quite resistant at first. One of the most depressing experiences I’d had as a child was listening to our family friend Paul talk about Vietnam. He was invariably drunk, reeking of alcohol. His memories seemed overwhelming: he’d suddenly start regaling us with stories of seeing men’s heads exploding, their faces blown to bits. His expression of horror and the physical manifestations of fear like flop sweat illustrated much more than his words how the experience of war had broken and devastated him. He’d talk about friends who were crippled or dead, and other brothers who came home physically whole but were no longer all there mentally. He warned us over and over not to sign up, that black men were even less valued by America when we were sent to war. I wanted no part of it.

Of course, as recruiters do, the army and air force representatives painted a very different picture. Emphasizing basketball and college study, stressing that the country was at peace, they glossed over the main job of the military. No mention was made at all of war or combat. I didn’t have to worry about that. They implied that all I’d have to do was take a few orders and stay physically fit. They explained how in the military—unlike in college—not only could I play ball; I could get nearly free college tuition, too. They praised my intelligence and my skills and kept the focus on what was in it for me.

As I saw it, my only other alternative was to apply for financial aid, but I had no idea how I’d be able to raise the rest of the money to pay for the full tuition and room and board. The idea of continuing to be dependent on my mother distressed me. And I knew I couldn’t stay home and face the disappointment of my sisters and Big Mama, who had cheered on my athletic career and encouraged me to stick with school. I certainly couldn’t handle the smirks of my rivals if I didn’t leave Miami to play college basketball somewhere. And so, before long, I found myself no longer considering whether to sign up but trying to decide whether the air force or the army was the better option.

Again, a random choice—one that might seem completely unlikely—put me on the path to my future. I met several times with each recruiter. The army recruiter was a brother. He tried to sell me on his branch of the armed services by demonstrating how cool he was and by extension, how cool I could be if I joined the army. As you know by now, this normally would have sealed the deal with me, but I didn’t buy it from him. I felt that he was trying too hard. His behavior wasn’t authentic; he seemed like a fraud to me.

In contrast, the air force recruiter was a classic white dork. He made no attempt to be cool or to pretend that he was anything like me. Instead he was straightforward and made a plainspoken pitch. He understood intuitively that he’d never be able to impress me by trying to be something he so obviously was not—and that in itself made an impression. It made him seem trustworthy.

Still, I kept considering both branches of the military. I may have inadvertently fallen for one of the oldest behavioral tricks there is. That is, being presented with two options when I’d initially wanted none of them, but then seeing my choice as one of those two and forgetting any other possibilities. At one moment, I found myself staring at the army green uniform and thinking, I can’t do that, can’t do that. That shit’s not for me. It offended my sense of style, somehow. I couldn’t picture myself dressed that way, ever. Then I’d think about basketball and scholarships and think, Maybe.

Later, at one meeting with the army recruiter and his superior officer, I actually fell asleep because I’d been out so late the night before with a girl. Falling asleep in class wasn’t uncommon for me, but that was the first time I’d done it in a small meeting. The guy started pressuring me because he said my napping had embarrassed him in front of his boss, so I should sign up to make it right. But then I started thinking again about the horrible green uniform and what the air force might be like instead.

Finally, I went back to the air force recruiter. I had come to associate the army with some of the less intelligent brothers I knew: that was the branch of the service they seemed to join. The air force had an advantage here, especially since I remained flattered that I’d attained the higher intelligence score needed to join. Their uniform wasn’t entirely intolerable, certainly not as awful as that army green.

The airmen were sharper, in both mind and dress. It sounds a bit weird thinking back on it, but again, another not-totally-considered choice—preferring the blue of the air force to the army green; wanting to be part of a service that required a higher IQ—put me on the path to science.

Because I was still only seventeen, my mother had to sign off on my enlistment as well. It was an ironic moment for me. MH was sitting at a table at Grandmama’s house, with all the paperwork in front of her. The air force recruiter was there, showing us how to fill out the paperwork. Suddenly, she paused. She looked up at me before she finished signing and asked, “Are you sure you want to do this?” Remembering all the times she hadn’t been there when I needed guidance, I thought to myself, Oh, now you wanna play mommy? Just sign the fucking papers. I felt as though she was only feigning maternal behavior to impress the recruiter.

Don’t try to change yourself; change your environment.

—

B. F. SKINNER

T

he military has its indoctrination down to a science. They know how to use experiences like exhaustion, peer pressure, isolation from one’s friends and family, and disorientation to maximum effect in boot camp, or basic training, as it’s formally known. Even though the physical challenges were nothing compared to the workouts I’d already done throughout high school, the mental challenges to my ideas about myself, about race, about self-control, and about what I wanted were immediate and at times, daunting. I started on August 24, 1984.

The night before I left, the air force had agreed to pay for a hotel room near the airport so I would be sure to be on time for my early morning flight to Dallas. I stayed up nearly all night with my high school friends, knowing it could be the last time we’d really get to hang. We were laughing and joking, the guys telling me that I’d come back all “shot out,” or brainwashed like other guys from the neighborhood who’d joined the service. But I wasn’t anxious at all until the morning came and I headed for the airport. It would be the first time I’d ever flown.

Although it would have been just as easy for the military to fly us directly to San Antonio, we were sent instead to Dallas, where we had to wait for hours at the airport. Then we took an extended bus ride to Lackland Air Force Base.

It’s ingenious because the exhaustion starts to wear you down before you even know it. When we finally got to Lackland, it was about midnight. And it still wasn’t time to rest. For what seemed like hours, we were made to stand at attention, the boredom and physical stress of the position draining our minds and our bodies. There were no clocks and, of course, not knowing what time it was added to the discomfort and disorientation.

At some point, the training instructors came out yelling. Hurling abuse at us and calling us pathetic mama’s boys, they began the next phase of our indoctrination. I thought to myself, This is a fucking joke, and almost laughed because it was so much like every clichéd boot camp scene I’d watched in movies like

Private Benjamin

and

An Officer and a Gentleman

. There they were, like drill sergeants out of Central Casting, ridiculing our dress, five o’clock shadow, and overall lack of competence.

Soon they targeted one of the biggest men among the recruits for an extra heaping of humiliation. He was a white guy, huge and incredibly built.