History of the Second World War (112 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

By the 18th, Luttwitz’s 47th Panzer Corps was closing on Bastogne with two armoured divisions (the 2nd and Panzer Lehr) and the 26th Volksgrenadier Division. But reinforcements (a combat command from the U.S. 9th Armored Division and engineer battalions) had arrived to help the defence. A struggle for each village, and transport confusion on the German side, slowed down the attack in time for the 101st Airborne Division, from Eisenhower’s strategic reserve, to reach Bastogne on the morning of the 19th, a crucial moment. (It was temporarily commanded by Brigadier Anthony C. McAuliffe, as its usual commander, Major-General Maxwell D. Taylor, was away on leave in America.) The fierce defence of Bastogne, in which the American engineers particularly distinguished themselves, made it impossible for the Germans to rush the town, and the panzer columns swung past on either side — they had already created a gap on the north of the town — leaving the 26th Volksgrenadier Division with a panzer battle-group to reduce this road-centre. Thus Bastogne was cut off on December 20.

It had been only on the morning of the 17th that Eisenhower and his principal subordinate commanders had begun to accept that a full-scale German offensive was under way — and it was not until the 19th that they were sure beyond doubt. Bradley ordered the 10th Armored Division northward and confirmed the initiative of Lieutenant-General William Simpson (of the 9th Army) in sending the 7th Armored Division southward, to follow the 30th Division. Thus over 60,000 fresh troops were moving to the threatened area, and 180,000 more were diverted thither in the next eight days.

The 30th Division (Major-General Leland S. Hobbs), out at rest near Aachen, was at first told to move to Eupen, then diverted to Malmedy, and then sent farther west to stop Peiper’s panzer battle-group. Part of Stavelot was retaken, with the help of fighter-bombers, and Peiper’s links with the rest of the 6th Panzer Army were cut, while he was meeting increasingly strong opposition at Stoumont. By the 19th he was desperately short of fuel while the arrival of the 82nd Airborne Division and armoured reinforcements turned the balance against him. Meanwhile the bulk of the two S.S. Panzer Corps were still stuck far in rear. There were insufficient roads for them to advance and deploy their mass of tanks and transport. (Peiper’s battle-group, ringed in and out of fuel, eventually began on the 24th to make its way back on foot, abandoning its tanks and other vehicles.)

Farther south, on Manteuffel’s front, the elements of the U.S. 3rd and 7th Armored Divisions had moved to bar the German advance westward from the St Vith area. The defenders of this town came under tremendous pressure from a strong attack directed by Manteuffel, and were soon forced out with heavy losses. Fortunately for them, a vast traffic jam hindered a quick exploitation, by the 66th Corps, and enabled the remnants of the U.S. 106th Division and 7th Armored Division to slip away to safer positions. That helped to hinder any long-range exploitation of the gap by a rapid advance towards the Meuse in this sector.

When the front was split open Eisenhower was prompted on the 20th to put Montgomery in charge of all the forces on the north side of the breach, including both the 1st and 9th U.S. Armies, and Montgomery had brought up his own reserve corps, the 30th (of four divisions), to guard the Meuse bridges.

His confident air was a great asset but the effect would have been better if he had not, as one of his own officers remarked, ‘strode into Hodges’ H.Q. like Christ come to cleanse the temple’. He aroused much wider resentment when at a Press conference later he conveyed the impression that his personal ‘handling’ of the battle had saved the American forces from collapse. He also spoke of having ‘employed the whole available power of the British Group of Armies’ and having ‘finally put it into battle with a bang’. That statement caused the more irritation because on the southern flank Patton had been counterattacking since December 22 — and relieved Bastogne on the 26th — whereas Montgomery had insisted that he must ‘tidy up’ the position first, and did not begin the counterthrust from the north until January 3, while keeping his British reserves out of the battle until then.

On the day of the regrouping of the Allied front, December 20, the northern side of the breach was put in the charge of Major-General J. Lawton Collins, whose U.S. 7th Corps had previously been engaged in the American offensive towards the River Roer, and the Rhine. Montgomery made it clear that he wanted Collins — whose nickname was ‘Lightning Joe’ — and no one else for this crucial task. He was given for his new role the picked 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions along with the 75th and 84th Infantry Divisions to mount a counterattack southward against Manteuffel’s advancing spearheads.

At Bastogne the situation was, and continued, critical. Repeated attacks forced the defenders back, but they were never overwhelmed. On the 22nd Luttwitz sent in a ‘white flag’ party calling on the beleaguered garrison to surrender on honourable terms, but merely got McAuliffe’s cryptic reply ‘Nuts!’ — which has since become legendary. The subordinate commander on this sector, in trying to make it intelligible to the Germans, could only express it as ‘Go to hell!’

Next day, the welcome advent of fine weather allowed the first supply drop by air, and many Allied air attacks on the German position. Meanwhile Patton’s forces were moving up from the south. Even so, the situation was still precarious, for on the 24th, Christmas Eve, the perimeter was reduced to sixteen miles. But Luttwitz’s troops were also receiving few reinforcements or supplies, while being increasingly pounded by the Allied air forces. On Christmas Day, the Germans made an all-out effort, but their newly arrived tanks suffered heavily and the defence was unbroken. Moreover the U.S. 4th Armored Division (now commanded by Major-General Hugh J. Gaffey), from Patton’s 3rd Army, had fought its way up from the south, and made contact with the garrison at 4.45 p.m. on the 26th. The siege was raised.

Although the German 7th Army had initially made some progress in its attempt to cover Manteuffel’s advancing left flank, its own weakness exposed it to a counterstroke from the south. By the 19th Patton had been told to abandon his own offensive through the Saar, and concentrate on wiping out the bulge Manteuffel had made, using two of his corps for the purpose. By the 24th his 12th Corps was pushing back the divisions of the German 7th Army, and eliminating the southern ‘shoulder’ they had tried to create.

Farther west the U.S. 3rd Corps (4th Armored with 26th and 80th Infantry Divisions) concentrated on the relief of Bastogne. The famous 4th Armored was on its toes to carry out Patton’s order of the 22nd, ‘Drive like hell’. But the ground favoured the defence, and the main opposition came from the tough paratroops, fighting on foot, of the 5th Parachute Division. They had to be prised out of every village and wood. Reconnaissance found, however, less opposition on the Neufchateau-Bastogne road, and on the 25th the thrust was switched to the north-east axis instead of direct. Next day some of the few remaining Sherman tanks of the 4th Armored got through to the southern defences of Bastogne.

Meanwhile Manteuffel’s panzer divisions, by-passing Bastogne, had been pushing on towards the Meuse, in the stretch south of Namur. To cover the crossings while fresh American forces were moving up, Horrocks’s British 30th Corps had moved on to the east, as well as the west, bank of the river around Givet and Dinant, while American engineers stood ready to blow the bridges.

Hitler, having shortened his sights, now had his vision focused on the Meuse. He released the 9th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions from his O.K.W. reserve to help Manteuffel in clearing the Marche-Celles area in the approaches to Dinant. Thus both sides were planning an offensive for Christmas Day, yet were too heavily engaged with each other to carry it out. But Collins’s troops were slowly gaining ground; on Christmas morning his forces (helped by the British 29th Armoured Brigade) regained the village of Celles, barely five miles from the Meuse and Dinant — the high-water mark of the German advance. Numerous isolated pockets were mopped up later by infantry, or wiped out by air attack. From December 23 on the panzer forces were severely harassed from the air, and by the 26th they were forbidden to try moving by day. The belated arrival of the 9th Panzer Division on Christmas evening failed to overcome the sturdy defence of the U.S. 2nd Armored Division. By the 26th the Germans were falling back — and the Meuse was recognised as unattainable.

Dietrich’s 6th Panzer Army had been told to make a fresh effort in support of Manteuffel’s thrust, converging south-west towards it, but although it brought its panzer divisions into action it made little progress against American defences that were now strongly reinforced, and readily backed by instantaneous fighter-bomber assaults. The 2nd S.S. Panzer Division made an initial penetration that caused alarm and confusion, but suffered heavy loss in a prolonged fight for the village of Manhay (twelve miles south-west of Trois Ponts). In sum, the 6th Panzer Army’s offensive had produced nothing but exhaustion.

Long before the main counteroffensive opened the Germans had abandoned their northern push, and failed in a final effort on the southern wing. This last bid had followed Hitler’s belated decision to switch his weight there and back up the 5th Panzer Army’s thrust. But the chance had gone. Bitterly, Manteuffel said: ‘It was not until the 26th that the rest of the reserves were given to me — and then they could not be moved. They were at a standstill for lack of petrol — stranded over a stretch of a hundred miles — just when they were needed.’* The irony of this situation was that on the 19th the Germans had come within a quarter of a mile of the huge fuel dump near Stavelot, containing some 2,500,000 gallons — a hundred times larger than the largest of the dumps they actually captured.

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of The Hill,

p. 463.

We had hardly begun this new push before the Allied counteroffensive developed. I telephoned Jodl and asked him to tell the Fuhrer that I was going to withdraw my advanced forces out of the nose of the salient we had made. . . . But Hitler forbade this step back. So instead of withdrawing in time, we were driven back bit by bit under pressure of the Allied attacks, suffering needlessly. — Our losses were much heavier in this later stage than they had been earlier, owing to Hitler’s policy of ‘no withdrawal’. It spelt bankruptcy, because we could not afford such losses.†

†

ibid.,

p. 464.

Rundstedt endorsed this verdict: ‘I wanted to stop the offensive at an early stage, when it was plain that it could not attain its aim, but Hitler furiously insisted that it must go on. It was Stalingrad No. 2.’*

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

p. 464.

The Allies had come near disaster at the start of the Ardennes battle through neglecting their defensive flank. But in the end it was Hitler who carried to the extreme the military belief that ‘attack is the best defence’. It proved the ‘worst defence’ — wrecking Germany’s chances of any further serious resistance.

PART VIII – FINALE 1945

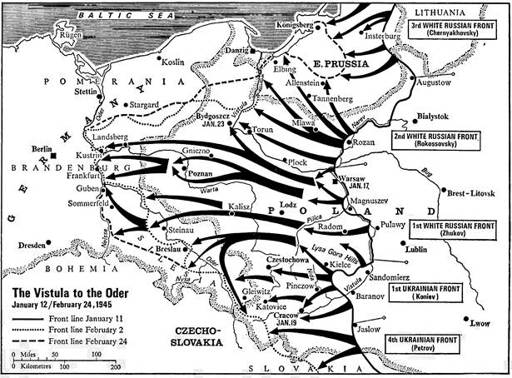

CHAPTER 36 - THE SWEEP FROM VISTULA TO ODER

Stalin had notified the Western Allies that he would launch a fresh offensive from the Vistula line about the middle of January, to coincide with their intended attack on the Rhine line — now delayed by the dislocation caused by the Ardennes counteroffensive. No great expectations were built on the Russian offensive by high quarters in the West. Some of the Russian reservations about weather conditions, the continued withholding of adequate information about the Russian forces, and the prolonged standstill since the Russians’ arrival on the Vistula at the end of July had contributed to a revival of the tendency to underestimate what the Russians could do.

Before the end of December ominous reports were received by Guderian — who, in this desperately late period of the war, had been made Chief of the General Staff. Gehlen, the head of the ‘Foreign Armies East’ section of Army Intelligence, reported that 225 Russian infantry divisions and twenty-two armoured corps had been identified on the front between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians, assembled ready to attack.

But when Guderian presented this ominous report of the massive Russian preparations, Hitler refused to believe it, and exclaimed: ‘It’s the biggest imposture since Jenghiz Khan! Who is responsible for producing all this rubbish?’ Hitler preferred to rely on the reports of Himmler and the S.S. Intelligence service.

Hitler rejected the idea of stopping the Ardennes counteroffensive and transferring troops to the Eastern Front, on the ground that it was of prime importance to keep the initiative in the West which he had ‘now regained’. At the same time he refused Guderian’s renewed request that the army group (of twenty-six divisions) now isolated in the Baltic States should be evacuated by sea and brought back to reinforce the gateways into Germany.