History of the Second World War (37 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

CHAPTER 17 - JAPAN’S TIDE OF CONQUEST

The execution of the plan of attack on Pearl Harbor owed as much to Admiral Yamamoto’s impulsion as had its adoption. For many months a stream of information, particularly about American ship movements, flowed in from the trained naval Intelligence officers who had been posted to the Japanese consulate in Honolulu. In the Japanese fleet itself the crews of ships and aircraft were intensively trained for the operation, and to carry it out in all kinds of weather; at least fifty practice flights were made by the bomber crews.

As already mentioned, the plan was much helped by the recently increased range of the Zero fighter type, which freed the carrier fleet from having to aid the South-west Pacific operations. It profited also from the evidence of the British naval attack on Taranto in November 1940, where the British Fleet Air Arm had succeeded, with only twenty-one torpedo-bombers, in sinking three Italian battleships lying in a strongly fortified harbour. Even then it had not been considered possible to launch aerial torpedoes in water where the depth was less than 75 feet — which was about the average at Taranto — and Pearl Harbor had thus been regarded as immune from that kind of attack, as the depth there was only 30-45 feet. But by 1941 the British, applying their experience at Taranto, had become able to launch aerial torpedoes in barely 40 feet depth of water, by fitting wooden fins that prevented them from ‘porpoising’ and hitting the shallow sea-bottom.

Learning these details from their embassies in Rome and London, the Japanese were stimulated to press on with similar experiments. Moreover, to make their planned attack more effective, their high-level bombers were equipped with 15-inch and 16-inch armour-piercing shells fitted with fins so that they would fall like bombs. Dropped vertically, no deck-armour could withstand them.

The United States Pacific Fleet could have countered the ‘Taranto’ danger by fitting its larger ships with anti-torpedo nets — and that possibility worried the Japanese — but Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, its Commander-in-Chief, had taken the view, like the Navy Department, that the cumbersome nets then available would be too much of a hindrance to quick movement of ships and to boat traffic. As the event showed, that decision virtually doomed the fleet at Pearl Harbor.

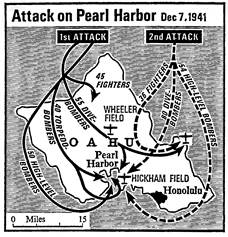

A combination of factors determined the date of the attack. The Japanese knew that Admiral Kimmel always brought his fleet back into Pearl Harbor during the weekend, and that the ships would not be fully manned then, thus increasing the effect of a surprise attack. So a Sunday was the natural choice. After mid-December the weather was likely to be unfavourable for amphibious landings in Malaya and the Philippines, as the monsoon would be at its peak, and unfavourable also for the refuelling at sea of the force to attack Pearl Harbor. On December 8 (Tokyo time), a Sunday at Hawaii, there would be no moonlight, and the consequent cloak of darkness would aid the surprise approach to Hawaii of the carrier force. The tides there would also be favourable for landings, an idea which was originally considered, although eventually rejected for lack of troopships and because the approach of such an invasion force was likely to be detected.

In choosing the approach route of the naval striking force, three alternatives were considered. One was a southerly route via the Marshall Islands, and another was a central route via the Midway Islands. These were the shorter, but they were discarded in favour of a northerly approach from the Kurile Islands — which would mean refuelling — because this avoided the shipping routes and also carried less risk of being spotted by the American reconnaissance aircraft patrols.

The Japanese also benefited from the use of what has been called the ‘unequal leg’ attack. Approaching in darkness, the carriers launched their planes at first light when at the nearest point to the target, then turned away from the target but not on a directly reversed route, and were re-joined by their aircraft at a point farther from the target than when they had been launched. Thus the Japanese aircraft flew one short, and one long, leg — whereas pursuing American aircraft would have to fly two long legs, one out and one back. That disadvantage had not been considered by the American defence planners.

The targets, in order of importance, were: the American carriers (it was hoped by the Japanese that as many as six, and at least three, would be at Pearl Harbor); the battleships; the oil tanks and other port installations; the aircraft on the main bases at Wheeler, Hickam, and Bellows Field. The force used for this stroke by the Japanese was six carriers, carrying a total of 423 aircraft, of which 360 were employed in the attack — 104 high-level bombers, 135 dive-bombers, and forty torpedo-bombers, with eighty-one fighters. The escorting force consisted of two battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, and three submarines, with eight accompanying tankers; it was under Admiral Nagumo. There was also planned to be a simultaneous attack by midget submarines, to take advantage of the expected chaos.

On November 19 the submarine force left Kure naval base in Japan, with five midget submarines in tow. The main task force assembled on the 22nd at Tankan Bay in the Kurile Islands, and left on the 26th. On December 2 it received word that the attack orders were confirmed, so ships were darkened; even then there was the proviso that the mission would be abandoned if the fleet was spotted before December 6 — or if a last-minute settlement was reached in Washington. On the 4th the final refuelling took place, and speed was increased from 13 to 25 knots.

Continuous reports were reaching it, via Japan, from the Honolulu consulate, so there was disappointment when on the 6th, the eve of the stroke, no carriers were reported in Pearl Harbor. (Actually one was on the Californian coast, another was taking bombers to Midway, and another had just delivered fighters to Wake, while three were in the Atlantic.) However, eight battleships were reported to be in Pearl Harbor, and without torpedo nets, so Admiral Nagumo decided to go ahead. The aircraft were launched between 0600 and 0715 hours (Hawaii time) next morning, about 275 miles due north of Pearl Harbor.

There were two late warnings that might have made a difference to the outcome, but did not. The first was that the approach of the Japanese submarine force was detected, several times from 0355 hours onward; one of the submarines was sunk at 0651 by U.S. destroyers and another at 0700 by naval aircraft. Then the most northerly of the six American radar stations on the island detected a large force of aircraft, evidently over a hundred, approaching soon after 0700. But this was interpreted by the information centre as being a number of B.17s that was expected from California — although it comprised only twelve planes and these were coming from the east, not the north.

The attack started at 0755 and went on until 0825; then a second wave, of dive-bombers and high-level bombers, struck at 0840. But the use of the torpedo-bombers in the first wave had been the decisive factor.

Of the eight American battleships, the

Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia

and

California

were sunk, and the

Maryland, Nevada, Pennsylvania,

and

Tennessee

were severely damaged.* Sunk, too, were three destroyers and four smaller vessels, while three light cruisers and a seaplane tender were badly damaged. Of American aircraft, 188 were destroyed, and sixty-three damaged. The Japanese loss was only twenty-nine planes destroyed and seventy damaged — apart from the five midget submarines which were lost in an attack that was a complete failure. Of human casualties, the Americans had 3,435 killed or wounded; while the Japanese figure is more uncertain, the killed were under a hundred.

* The

Nevada

was beached; the

California

was later refloated.

The returning Japanese aircraft landed on the carriers between 1030 and 1330 hours. On December 23 the main task force itself arrived back in Japan.

The coup brought three great advantages to Japan. The United States Pacific Fleet was virtually put out of action. The operations in the South-west Pacific were made secure against naval interference, while the Pearl Harbor task force could be employed to support those operations. The Japanese now had more time to extend and build up their defensive ring.

The main drawbacks were that the stroke had missed the U.S. carriers — its prime target, and key one for the future. It had also missed the oil tanks and other important installations, whose destruction would have made the American recovery much slower, as Pearl Harbor was the only full fleet base. Coming as a surprise, apparently before any declaration of war, it aroused such indignation in America as to unite public opinion behind President Roosevelt, and in violent anger against Japan.

Ironically, the Japanese had intended to keep within the bounds of legality while profiting from the value of surprise — in other words, going as close to the border as they could without violating it. Their reply to the American demands of November 26 was timed so that it should be sent to the Japanese Ambassador in Washington in the late evening of Saturday, December 6, and was to be delivered to the United States Government at 1300 hours on the Sunday — which would be 0730 in the morning by Hawaii time. That would give the United States scant chance — about half an hour — of notifying its commanders in Hawaii and elsewhere that war had come, but could be claimed as legally correct by international law. Owing, however, to the length of the Japanese Note (5,000 words) and delays in decoding it at the Japanese Embassy, it was not ready for delivery by the Ambassador until 1420 hours Washington time — which was about 35 minutes

after

the start of the Pearl Harbor attack.

The violence of the American denunciation of Pearl Harbor as barbarous behaviour, and the way it came as a surprise, were astonishing in the light of history. For the Japanese attack had a close parallel with their attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, and had been foreshadowed by it.

In August 1903, negotiations had begun between Japan and Russia for a settlement of their differences in the Far East. But after 5½ months, the Japanese Government came to the conclusion that the Russian attitude offered it no satisfactory arrangement, and on February 4, 1904, decided to use force. On the 6th, negotiations were broken off — but without any declaration of war. The Japanese fleet, under Admiral Togo, sailed secretly for Port Arthur, the Russian naval base. On the night of the 8th, Togo launched his torpedo-boats against the Russian squadron anchored at Port Arthur. Taking it by surprise, he disabled two of its best battleships, and a cruiser — with the result that Japanese naval supremacy was henceforth established in the Far East. It was only on the 10th that the Japanese declaration of war was issued and the Russian at the same time.