History of the Second World War (94 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The commander of the army in that part of Normandy was also away — directing an exercise in Brittany. The commander of the panzer corps that lay in reserve had gone on a visit to Belgium. Another key commander is said to have been away spending the night with a girl. Eisenhower’s decision to proceed with the landing despite the rough sea turned out greatly to the Allies’ advantage.

A strange feature of the weeks that followed was that, although Hitler had correctly guessed the site of the invasion, once it had taken place he became obsessed with the idea that it was only a preliminary to a second and larger landing

east

of the Seine. Hence he was reluctant to let reserves be moved from that area to Normandy. This belief in a second landing was due to the Intelligence Staff’s gross overestimate of the number of Allied divisions still available on the other side of the Channel. That was partly due to the British deception plan. But it was also another result of, and testimony to, the way that Britain was ‘watertight’ against spying.

When the initial countermoves broke down, and had obviously failed to prevent the Allies’ continued build-up in the bridgehead, Rundstedt and Rommel soon came to realise the hopelessness of trying to hold on to any line so far west.

Relating the sequel, Blumentritt said:

In desperation, Field-Marshal von Rundstedt begged Hitler to come to France for a talk. He and Rommel together went to meet Hitler at Soissons on June 17, and tried to make him understand the situation. . . . But Hitler insisted that there must be no withdrawal — ‘You must stay where you are.’ He would not even agree to allow us any more freedom than before in moving the forces as we thought best. . . . As he would not modify his orders, the troops had to continue clinging on to their cracking line. There was no plan any longer. We were merely trying, without hope, to comply with Hitler’s order that the line Caen-Avranches must be held at all costs.*

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

p. 409

Hitler swept aside the field-marshals’ warnings by assuring them that the new V weapon, the flying bomb, would soon have a decisive effect on the war. The field-marshals then urged that, if this weapon was so effective, it should be turned against the invasion beaches — or, if that was technically difficult, against the invasion ports in southern England. Hitler insisted that the bombardment must be concentrated on London ‘so as to convert the English to peace’.

But the flying bombs did not produce the effect that Hitler had hoped, while the Allied pressure in Normandy increased. When asked one day on the telephone from Hitler’s H.Q.: ‘What shall we do?’ Rundstedt retorted: ‘End the war! What else can you do.’ Hitler’s solution was to sack Rundstedt, and replace him by Kluge, who had been on the Eastern Front.

‘Field-Marshal von Kluge was a robust, aggressive type of soldier’, Blumentritt remarked. ‘At the start he was very cheerful and confident — like all newly appointed commanders. . . . Within a few days he became very sober and quiet. Hitler did not like the changing tone of his reports.’†

†

ibid.,

p. 413.

On July 17th Rommel was badly injured when his car crashed, after being attacked on the road by Allied planes. Then, three days later, on the 20th, came the attempt to kill Hitler at his headquarters in East Prussia. The conspirators’ bomb missed its chief target, but its ‘shock wave’ had terrific repercussions on the battle in the West at the critical moment. Blumentritt recalled:

When the Gestapo investigated the conspiracy . . . they found documents in which Field-Marshal von Kluge’s name was mentioned, so he came under grave suspicion. Then another incident made things look worse. Shortly after General Patton’s break-out from Normandy, while the decisive battle at Avranches was in progress, Field-Marshal von Kluge was out of touch with his headquarters for more than twelve hours. The reason was that he had gone up to the front, and there been trapped in a heavy artillery bombardment. . . . Meantime, we had been suffering ‘bombardment’ from the rear. For the Field-Marshal’s prolonged ‘absence’ excited Hitler’s suspicion immediately, in view of the documents that had been found . . . Hitler suspected that the Field-Marshal’s purpose in going right up to the front was to get in touch with the Allies and negotiate a surrender. The Field-Marshal’s eventual return did not calm Hitler. From this date onward the orders which Hitler sent him were worded in a brusque and even insulting language. The Field-Marshal became very worried. He feared that he would be arrested at any moment — and at the same time realized more and more that he could not prove his loyalty by any battlefield success.

All this had a very bad effect on any chance that remained of preventing the Allies from breaking out. In the days of crisis Field-Marshal von Kluge gave only part of his attention to what was happening at the front. He was looking back over his shoulder anxiously — towards Hitler’s headquarters.

He was not the only general who was in that state of worry for conspiracy in the plot against Hitler. Fear permeated and paralysed the higher commands in the weeks and months that followed.*

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

pp. 414-15.

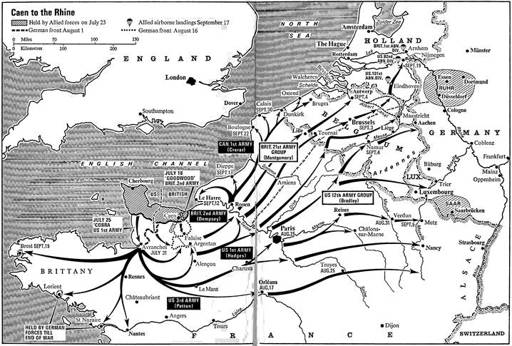

On July 25 the U.S. First Army launched a fresh offensive, ‘Cobra’, while the recently landed Patton’s Third Army was ready to follow it up. The last German reserves had been thrown in to stop the British. On the 31st the American spearhead burst through the front at Avranches. Pouring through the gap, Patton’s tanks quickly flooded the open country beyond. On Hitler’s orders the remnants of the panzer forces were scraped together, and used in a desperate effort to cut the bottleneck at Avranches. The effort failed — whereat Hitler caustically said: ‘It only failed because Kluge didn’t want to succeed.’ All that remained of the German armies now tried to escape from the trap in which they had been kept by Hitler’s ban on any timely withdrawal. A large part were trapped in the ‘Falaise Pocket’, and the survivors had to abandon most of their heavy arms and equipment in crossing back over the Seine.

Kluge was then sacked. On the way home he was found dead in his car, having swallowed a poison capsule — as his Chief of Staff explained, ‘he believed he would be arrested by the Gestapo as soon as he arrived home’.

It was not only on the German side that stormy recriminations arose within the High Command. Fortunately those on the Allied side had no such serious consequences on the issue or to individuals although they left sore feelings that were of ill effect later.

The biggest ‘blow-up’ behind the scenes occurred over a near break-out by the British a fortnight before the Americans actually burst open the front at Avranches. This British blow, by the Second Army under Dempsey, was struck on the extreme opposite flank, east of Caen.

It was the most massive tank attack of the whole campaign, delivered by three armoured divisions closely concentrated. They had been stealthily assembled in the small bridgehead over the Orne, and poured out from it on the morning of July 18, after an immense carpet of bombs had been dropped, for two hours, by two thousand heavy and medium bomber aircraft. The Germans on that sector were stunned, and most of the prisoners taken were so deafened by the roar of the explosions that they could not be interrogated until at least twenty-four hours later.

But the defences were deeper than British Intelligence had thought.

Rommel, expecting such a blow, had hurried their deepening and reinforcement — until, on the eve of the attack, he was himself caught and knocked out by British aircraft, near the aptly named village of Sainte Foy de Montgomery. Moreover the enemy had heard the massive rumble of tanks as the British armour moved eastwards by night for the attack. Dietrich, the German Corps commander, said that he was able to hear them over four miles away, despite diverting noises, by pressing his ear to the ground — a trick he had learned in Russia.

The brilliant opening prospect faded soon after passing through the forward layers of the defence. The leading armoured division became entangled amid the village strongholds behind — instead of by-passing them. The others were delayed by traffic congestion in getting out of the narrow bridgehead, and the spearhead had come to a halt before they came on the scene. By the afternoon the great opportunity had slipped away.

This miscarriage has long been enshrouded in mystery. Eisenhower in his report spoke of it as an intended ‘breakthrough’, and as a ‘drive . . . exploiting in the direction of the Seine basin and Paris’. But all the British histories written after the war declare that it had no such far-reaching aims, and that no breakthrough on this flank was ever contemplated.

They follow Montgomery’s own account, which insisted that this operation was merely ‘a battle of position’, designed to create a ‘threat’ in aid of the coming American break-out blow ‘and secondly to secure ground on which major forces could be poised ready to strike out to the south and south-east, when the American break-out forces thrust eastwards to meet them.’

Eisenhower in his post-war memoirs tactfully glides over the matter by avoiding any mention of this battle, while Churchill makes only the barest reference to it.

Yet anyone behind the scenes at the time was acutely aware of the violent storm that blew up. The air chiefs were very angry, especially Tedder. The state of temper is revealed in the diary of Captain Butcher, Eisenhower’s naval aide. ‘Around evening Tedder called Ike and said Monty had, in effect, stopped his armour from going further. Ike was mad.’ According to Butcher, Tedder next day telephoned Eisenhower from London and conveyed that the British Chiefs of Staffs were ready to sack Montgomery if requested, although this is denied by Tedder in his own account of the affair.*

* Lord Tedder:

With Prejudice

, p. 563.

It was thus natural that on Montgomery’s side the immediate reaction to such complaints should have been to assert that the idea of a break-out on this flank had never been in mind. That assertion soon became an article of belief, and has since come to be accepted without question by military chroniclers. Yet it did not tally with the racy note of the codename given to this attack — ‘Operation Goodwood’, after the English racecourse. Nor with the term ‘broke through’ that Montgomery used in his first announcement of the attack on the 18th. Moreover his remark that he was ‘well satisfied with the progress made’ on the first day seemed hard to reconcile with the absence of a renewed effort of similar scale on the second day. That infuriated the air chiefs, who would not have agreed to divert the heavy bomber armada to the aid of a ground operation had they not believed that the aim of ‘Goodwood’ was a mass break-out.

Montgomery’s later assertion was a half-truth, and did himself an injustice. He had not planned to break out on this flank, and was not banking on it. But he would have been foolish not to reckon with the possibility of a German collapse, under this massive blow, and exploit it if it occurred.

Dempsey, who commanded the Second Army, thought a speedy collapse was likely, and had moved up himself to the armoured corps H.Q. so as to be ready to exploit it: ‘What I had in mind was to seize all the crossings of the Orne from Caen to Argentan’ — that ‘would establish a barricade across the Germans’ rear, and trap them more effectively than any American break-out on the Western flank could do. Dempsey’s hope of a complete breakthrough was very close to fulfilment at midday on July 18. In view of his revelation of what he had in mind it is amusing to note the many assertions that there was no idea of trying to reach Falaise — for Argentan, his prospective goal, was nearly twice as far.

Dempsey, too, was shrewd enough to realise that the disappointment of his hopes might be turned to compensating advantage. When one of his staff urged him to protest against press criticism of the failure of ‘Goodwood’, he replied: ‘Don’t worry — it will aid our purpose, and act as the best possible cover-plan.’ The American break-out on the opposite flank certainly owed much to the way that the enemy’s attention had been focused on the threat of a break-out near Caen.

But the break-out at Avranches, far to the west, carried no such immediate chance of cutting off the German forces. Its prospects depended on making a very rapid sweep eastward, or on the enemy clinging onto his position until he could be trapped.

In the event, when the break-out came at Avranches, on July 31, only a few scattered German battalions lay in the ninety-mile-wide corridor between that point and the Loire. So American spearheads could have driven eastward unopposed. But the Allied High Command threw away the best chance of exploiting this great opportunity by sticking to the outdated pre-invasion programme, in which a westward move to capture the Brittany ports was to be the next step.*