Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (18 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

11.58Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Verne’s chief source for the geology in the novel appears to have been a prolific French popular science writer named Louis Figuier (1819–1894). This indebtedness went unnoticed for over a century, only recently brought to light by William Butcher, a Verne scholar who translated the Folio Society’s illustrated edition of

A Journey to the Center of the Earth.

In a long article coauthored with John Breyer for the journal

Earth Sciences History,

he demonstrates that Verne leaned heavily on an 1863 book about earth history by Figuier titled

La terre avant le déluge,

which went into four editions and sold over 25,000 copies in two years.

35

As Butcher and Breyer note, the correspondences are so great and so numerous that Figuier, a fellow Parisian, might have been expected to cry

Zut alors!

when Verne’s novel came out and, if not sue him for plagiarism, at least give him a good biff on the nose. It’s hard to imagine that no one noticed, but apparently no one cared—an instance of literary laissez-faire that wouldn’t happen today. Here’s just one of many examples they cite:

A Journey to the Center of the Earth.

In a long article coauthored with John Breyer for the journal

Earth Sciences History,

he demonstrates that Verne leaned heavily on an 1863 book about earth history by Figuier titled

La terre avant le déluge,

which went into four editions and sold over 25,000 copies in two years.

35

As Butcher and Breyer note, the correspondences are so great and so numerous that Figuier, a fellow Parisian, might have been expected to cry

Zut alors!

when Verne’s novel came out and, if not sue him for plagiarism, at least give him a good biff on the nose. It’s hard to imagine that no one noticed, but apparently no one cared—an instance of literary laissez-faire that wouldn’t happen today. Here’s just one of many examples they cite:

From Verne:

I hadn’t gone a hundred yards further before incontrovertible proof appeared in front of my eyes. It was to be expected, for during the Silurian Period there were more than 1,500 species of vegetables and animals in the seas … On the walls could be clearly seen the outlines of seaweeds and Lycopodia … I picked up a perfectly-preserved shell, one that had belonged to an animal more or less like the present-day woodlouse. Then I caught up with my uncle and said to him:“See!”“Well,” he replied calmly, “it is the shell of a crustacean of the extinct order of trilobites. Nothing else.”

Compare this passage with Figuier:

Most trilobites … were able to roll themselves into a ball, like our woodlouse, doubtless to escape the attack of an enemy … The seas were already abundantly inhabited at the end of the Upper Silurian period, for naturalists today know more than 1,500 species, animal and vegetable, belonging to the Silurian period.

Similarly, the account of coal formation I quoted above is almost exactly as Figuier has it in

La terre avant le déluge.

Clearly Verne cribbed heavily from Figuier, and not only from his text. Butcher and Breyer also point out that Figuier’s book was illustrated, and a number of the descriptions of plants and animals in

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

are taken from these illustrations. “The third edition of Figuier’s

La terre avant le déluge,

” they write, “published in 1864, contained ‘twenty-five ideal views of landscapes of the ancient world’ drawn by Edouard Riou (1833–1900) … Riou also provided 56 illustrations for

Journey to the Centre of the Earth

in 1864.” Chummy of them, no? Butcher and Bryer summarize Figuier’s views—and by default Verne’s—thus: “Figuier advocated a directionalist view of earth history and progressionism in the organic realm. He thus fits squarely in the catastrophist camp. Moreover, like other members of this school, Figuier openly proclaimed his strong religious beliefs in his text, interpreting earth history and the progress of life as the visible working of the will of the Creator.”

La terre avant le déluge.

Clearly Verne cribbed heavily from Figuier, and not only from his text. Butcher and Breyer also point out that Figuier’s book was illustrated, and a number of the descriptions of plants and animals in

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

are taken from these illustrations. “The third edition of Figuier’s

La terre avant le déluge,

” they write, “published in 1864, contained ‘twenty-five ideal views of landscapes of the ancient world’ drawn by Edouard Riou (1833–1900) … Riou also provided 56 illustrations for

Journey to the Centre of the Earth

in 1864.” Chummy of them, no? Butcher and Bryer summarize Figuier’s views—and by default Verne’s—thus: “Figuier advocated a directionalist view of earth history and progressionism in the organic realm. He thus fits squarely in the catastrophist camp. Moreover, like other members of this school, Figuier openly proclaimed his strong religious beliefs in his text, interpreting earth history and the progress of life as the visible working of the will of the Creator.”

As was true of Poe and Melville (not to mention Shakespeare), however, plagiarism can become inspired borrowing, genius transforming theft. Verne may not rise to this level, being more clever than truly brilliant, but he does infuse Figuier’s mundane science with a certain lyrical beauty, at least in places.

Probably the most stirring passage in the book owes its ideas almost entirely to Figuier, but it achieves a poetic quality found nowhere in the source. I refer to Axel’s waking dream while they’re scudding across the Central Sea on a raft of partially fossilized wood, in which Axel has the entire history of the earth flash before his eyes—backward—in a sort of cosmogony-recapitulates-phylogeny rapture:

I fancied I could see floating on the water some huge

chersites

, antediluvian tortoises like floating islands. Along the dark shore there passed the great mammals of early times, the

leptotherium

, found in the caves of Brazil, and the

merycotherium

, found in the icy regions of Siberia. Farther on, the

pachydermatous lophiodon

, a gigantic tapir, was hiding behind the rocks, ready to dispute its prey with the

anoplotherium

, a strange animal which looked like an amalgam of rhinoceros, horse, hippopotamus and camel, as if the Creator, in too much of a hurry during the first hours of the world, had combined several animals in one. The giant mastodon waved its trunk and pounded the rocks on the shore with its tusks, while the megatherium, buttressed on its enormous legs, burrowed in the earth, rousing the echoes of the granite rocks with its roars. Higher up, the

protopitheca

, the first monkey to appear on earth, was climbing on the steep peaks. Higher still, the pterodactyl, with its winged claws, glided like a huge bat through the dense air. And finally, in the upper strata of the atmosphere, some enormous birds, more powerful than the cassowary and bigger than the ostrich, spread their vast wings and soared upwards to touch with their heads the ceiling of the granite vault.The whole of this fossil world came to life again in my imagination. I went back to the scriptural periods of creation, long before the birth of man, when the unfinished world was not yet ready for him. Then my dream took me even farther back into the ages before the appearance of living creatures. The mammals disappeared, then the birds, then the reptiles of the Secondary Period, and finally the fishes, crustaceans, mollusks, and articulated creatures. The zoophytes of the transitional period returned to nothingness in their turn. The whole of life was concentrated in me, and my heart was the only one beating in that depopulated world. There were no more seasons or climates; the heat of the globe steadily increased and neutralized that of the sun. The vegetation grew to gigantic proportions, and I passed like a ghost among arborescent ferns, treading uncertainly on iridescent marl and mottled stone; I leaned against the trunks of huge conifers; I lay down in the shade of

sphenophyl-las

,

asterophyllas

, and

lycopods

a hundred feet high.Centuries passed by like days. I went back through the long series of terrestrial changes. The plants disappeared; the granite rocks softened; solid matter turned to liquid under the action of intense heat; water covered the surface of the globe, boiling and volatizing; steam enveloped the earth, which gradually turned into a gaseous mass, white-hot, as big and bright as the sun.In the centre of this nebula, which was fourteen hundred thousand times as large as the globe it would one day form, I was carried through interplanetary space. My body was volatized in its turn and mingled like an imponderable atom with these vast vapours tracing their flaming orbits through infinity.What a dream this was!

A rhapsody of geology! It doesn’t really matter that the substance was lifted from Figuier; Verne has found the silver in the ore. And not too much farther along, he does something else quite wonderful and historic: he gives us the very first battle in literature between two dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs were a fairly new invention when Verne was writing. Not the fossils and skeletons themselves, of course, but the

idea.

The word “dinosaur” was coined in 1841 by British anatomist Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892), sometime physician, tutor to Queen Victoria’s children, head of the natural history department at the British Museum from 1856 to 1884, and longtime friend of Darwin until the younger man’s rising star seemed to eclipse his own, transforming Owen into a bitter enemy both of Darwin and evolutionism.

idea.

The word “dinosaur” was coined in 1841 by British anatomist Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892), sometime physician, tutor to Queen Victoria’s children, head of the natural history department at the British Museum from 1856 to 1884, and longtime friend of Darwin until the younger man’s rising star seemed to eclipse his own, transforming Owen into a bitter enemy both of Darwin and evolutionism.

One of the earliest specimens was unearthed in the United States in 1818 by Solomon Ellsworth Jr. while he was digging a well on his farm east of the Connecticut River. But discoveries in the 1820s in southern England by minister and geologist William Buckland (among the most famous of the antievolutionary “scriptural geologists”) and physician Gideon Mantell gained more notice. Owen, something of a showman, collaborated with sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to create the first of the dinosaur reconstructions that are now a staple of natural history museums everywhere, making life-sized models of

Iguanodon

and

Hylaeosaurus

(two of the first three dinosaurs to be named) that were put on display in the Crystal Palace of London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, setting off a dinosaur mania that cheerfully continues today.

Iguanodon

and

Hylaeosaurus

(two of the first three dinosaurs to be named) that were put on display in the Crystal Palace of London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, setting off a dinosaur mania that cheerfully continues today.

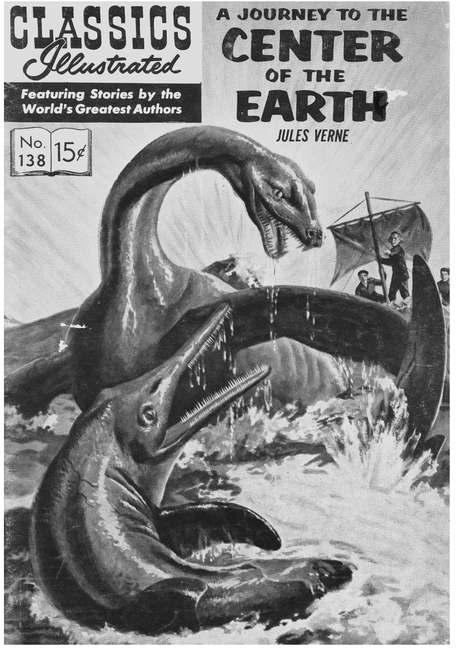

It was in its first blush when Verne cannily pitted his two sea monsters against each other in mortal combat. Again, Becker and Breyer point out that one of the Riou illustrations in the third edition of Figuier’s book showed “an ichthyosaurus emerging from the depths to confront a plesiosaur on the surface with its neck arched preparing to strike.” The very same pair Verne picked to go at it in his novel.

As the trio zip along over the Central Sea, they decide to take a sounding to determine its depth. They tie a pickax to a cord and drop it overboard but fail to strike bottom at two hundred fathoms; and when they haul it up, they find tooth marks on the ax head! Worrywart Axel starts to sweat about what might be down there. He remembers that “the antediluvian monsters of the Secondary Period … held absolute sway over the Jurassic seas.” And further observes:

Nature had endowed them with a perfect constitution, gigantic proportions, and prodigious strength. The saurians of our days, the biggest and most terrible alligators and crocodiles, are only feeble, reduced copies of their ancestors of primitive times.

This not only sets the stage nicely, it’s another bit of progressivism/ directionalism, which holds that things are falling from a former more intense state; not only were geologic forces stronger in the past, but plants and creatures tended to degenerate from an initial perfection at their first appearance. Two days later Axel’s fears are realized. With a terrific

thwack!

the raft is lifted “up above the water with indescribable force and hurled a hundred feet or more.” They see what they think is “a colossal porpoise,” “an enormous sea-lizard,” “a monstrous crocodile,” and “a whale!”

thwack!

the raft is lifted “up above the water with indescribable force and hurled a hundred feet or more.” They see what they think is “a colossal porpoise,” “an enormous sea-lizard,” “a monstrous crocodile,” and “a whale!”

“We stood there surprised, stupefied, horrified by this herd of marine monsters. They were of supernatural dimensions … a turtle forty feet long, and a serpent thirty feet long, darting its enormous head to and fro above the waves.” Suddenly two of them “hurled themselves on one another with a fury which prevented them from seeing us. The battle began two hundred yards away.” The Professor and Axel realize they hadn’t seen a herd of terrible creatures but different parts of these two. “The first of those monsters has the snout of a porpoise, the head of a lizard and the teeth of a crocodile … it’s the most formidable of the antediluvian reptiles, the ichthyosaurus! … The other is a serpent with a turtle’s shell, the mortal enemy of the first—the plesiosaurus!” Butcher and Breyer point out that the detail here too is drawn from Figuier, “who describes his ichthyosaur as having ‘the head of a lizard, the teeth of a crocodile, the vertebrae of a fish … and the fins of a whale.’” Verne also describes it as having a blood-red eye the size of a human head, another specific found in Figuier. But the latter never wrote this:

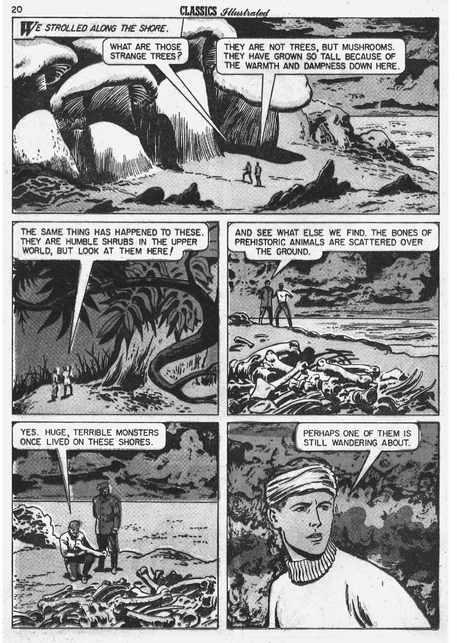

Those two animals attacked each other with indescribable fury. They raised mountainous waves which rolled as far as the raft, so that a score of times we were on the point of capsizing. Hissing noises of tremendous intensity reached our ears. The two monsters were locked together, and could no longer be distinguished from one another. We realized we had everything to fear from the victor’s rage. One hour, two hours went by, and the fight went on with unabated fury … Suddenly the ichthyosaurus and the plesiosaurus disappeared, creating a positive whirlpool in the water. Several minutes passed. Was the fight going to end in the depths of the sea?(above and opposite) Classics Comics edition of Verne’s

Journey to the Center of the Earth,

first published in May 1957. (© Gilberton Company, Inc.)All of a sudden an enormous head shot out of the water, the head of the plesiosaurus. The monster was mortally wounded. I could no longer see its huge shell, but just its long neck rising, falling, coiling, and uncoiling. Lashing the waves like a gigantic whip and writhing like a worm cut in two. The water spurted all around and almost blinded us. But soon the reptile’s death-agony drew to an end. Its movements grew less violent, its contortions became feebler, and the long serpentine form stretched out in an inert mass on the calm waves.As for the ichthyosaurus, has it returned to its submarine cave, or will it reappear on the surface of the sea?

Other books

The Amish Midwife by Mindy Starns Clark, Leslie Gould

Taking What's His (Entangled Brazen) by Diane Alberts

Wild Texas Rose by Jodi Thomas

Surrender by Rachel Carrington

Loving Teacher by Jade Stratton

Second Thoughts by Bailey, H.M.

Suprise by Jill Gates

The Devil You Know (Sarah Woods Mystery Book 15) by Jennifer L. Jennings

Red Desert - Point of No Return by Rita Carla Francesca Monticelli

Ruffly Speaking by Conant, Susan