Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (15 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

8.22Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

I would suggest an even wider reading—that

Pym

is also a send-up of the mania for polar exploration and the bright sunny possibilities being trumpeted by Reynolds & Co. Was Poe among the enthusiasts? Yes. Could he help seeing the dark humor in all this optimism? Or resist sticking it to the whole bunch, even though he admired Reynolds and thought the expedition was cool? It would seem not. The book’s commercial failure may have had less to do with its gory excesses and/or artistic deficiencies (it really

is

better and more fun to read than it’s supposed to be) than its naked subversiveness regarding this particular scene in the American Dream.

Pym

is also a send-up of the mania for polar exploration and the bright sunny possibilities being trumpeted by Reynolds & Co. Was Poe among the enthusiasts? Yes. Could he help seeing the dark humor in all this optimism? Or resist sticking it to the whole bunch, even though he admired Reynolds and thought the expedition was cool? It would seem not. The book’s commercial failure may have had less to do with its gory excesses and/or artistic deficiencies (it really

is

better and more fun to read than it’s supposed to be) than its naked subversiveness regarding this particular scene in the American Dream.

Interestingly, Poe found an ally in Henry David Thoreau, who also had something to say about the national enthusiasm Reynolds generated for exploration of the South Pole and about Symmes’ Hole too, though his comments in the concluding chapter of

Walden

(1854) were typically contrarian and transcendental, making metaphysics of it all:

Walden

(1854) were typically contrarian and transcendental, making metaphysics of it all:

What was the meaning of that South-Sea Exploring Expedition, with all its parade and expense, but an indirect recognition of the fact that there are continents and seas in the moral world to which every man is an isthmus or an inlet, yet unexplored by him, but that it is easier to sail many thousand miles through cold and storm and cannibals, in a government ship, with five hundred men and boys to assist one, than it is to explore the private sea, the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean of one’s being alone … It is not worth the while to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar. Yet do this even till you can do better, and you may perhaps find some “Symmes’ Hole” by which to get at the inside at last.

Good old Henry, ever marching along to that different drummer. Explore the Symmes’ Hole within you—it is more mysterious and profound.

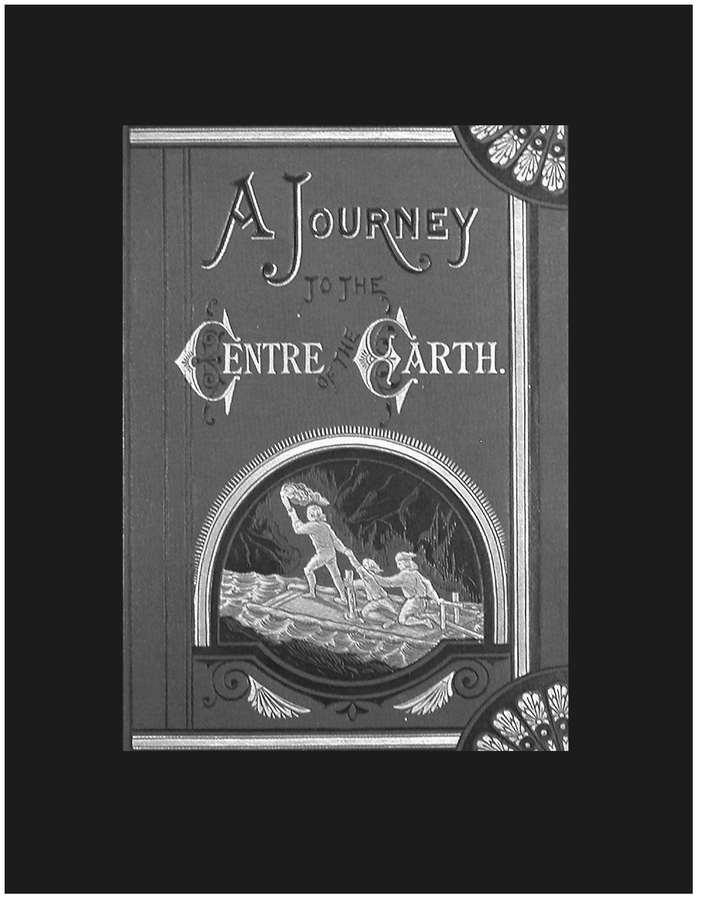

Deluxe edition of Jules Verne’s

A Journey to the Center of the Earth,

published by Scribner, Armstrong in 1874. (Courtesy of Sumner & Stillman, Booksellers)

A Journey to the Center of the Earth,

published by Scribner, Armstrong in 1874. (Courtesy of Sumner & Stillman, Booksellers)

4

JULES VERNE: A JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF GEOLOGY

FROM HERE, THE HOLLOW EARTH IS A CAROM SHOT

—from Poe to Baudelaire to Verne.

—from Poe to Baudelaire to Verne.

Poe died slowly, horribly, in Baltimore during the first week of October 1849. He had stopped there on his way from Richmond to Philadelphia, where he was to be paid $100 for editing a book of poems by Mrs. St. Leon Loud, such were his financial straits. Why he stopped in Baltimore isn’t known, nor what he did for five days between leaving the packet boat until he was found by his friend Dr. J. E. Snodgrass in a barroom, a wreck collapsed in an armchair. “His face was haggard,” Snodgrass later wrote, “not to say bloated, and unwashed, his hair unkempt and his whole physique repulsive.” Snodgrass took him to the Washington College Hospital, unconscious. Poe woke in the middle of the night to a pitiless swarm of DT symptoms, sweating, quaking, gibbering in a “busy but not violent or active delirium, the whole chamber seethed for him, and with vacant converse he talked to the spectres that withered and loomed on the walls.”

30

He lingered thus for days. Biographer Hervey Allen writes of his final hours:

30

He lingered thus for days. Biographer Hervey Allen writes of his final hours:

On that last night, as the shadow fell across him, it must have been the horrors of shipwreck, of thirst, and of drifting away into unknown seas of darkness that troubled his last dreams, for, by some trick of his ruined brain, it was scenes of

Arthur Gordon Pym

that rose in his imagination, and the man who was connected most intimately with them.“Reynolds!” he called, “Reynolds! Oh, Reynolds!” The room rang with it. It echoed down the corridors hour after hour all that Saturday night. The last grains of sand uncovered themselves as he slipped away, during the Sunday morning of October 7, 1849. He was now too feeble to call out any more. It was three o’clock in the morning and the earth’s shadow was still undisturbed by dawn. He became quiet, and seemed to rest for a short time. Then, gently moving his head, he said, “Lord help my poor soul.”

His tormented body had found rest, but his reputation lived on for continued abuse. It began with a savage obituary by Rufus Griswold, a former colleague at

Graham’s

magazine in the early 1840s whom Poe had unwisely chosen to be his literary executor. Griswold had been stewing over unkind things Poe had written in reviews of poetry anthologies Griswold had edited and began taking revenge in this

New York Daily Tribune

obituary published two days after Poe’s death—establishing the view of Poe as little more than a drug-ridden degenerate that would be the prevailing version of him in America for many years. During his lifetime his writing never attracted a large popular audience. To the general public he was known chiefly for “The Raven,” which was widely reprinted after it appeared in 1845. In a culture where “that d—-ed mob of scribbling women,” in Hawthorne’s famous frustrated phrase, sold the most books and stories, it is no wonder that Poe’s weird dark vision wasn’t welcome in the sunny optimistic America of the time, wormwood, not lemonade. And his scandalous personal habits made it even worse. For all his brilliance, he was an embarrassment, best forgotten.

Graham’s

magazine in the early 1840s whom Poe had unwisely chosen to be his literary executor. Griswold had been stewing over unkind things Poe had written in reviews of poetry anthologies Griswold had edited and began taking revenge in this

New York Daily Tribune

obituary published two days after Poe’s death—establishing the view of Poe as little more than a drug-ridden degenerate that would be the prevailing version of him in America for many years. During his lifetime his writing never attracted a large popular audience. To the general public he was known chiefly for “The Raven,” which was widely reprinted after it appeared in 1845. In a culture where “that d—-ed mob of scribbling women,” in Hawthorne’s famous frustrated phrase, sold the most books and stories, it is no wonder that Poe’s weird dark vision wasn’t welcome in the sunny optimistic America of the time, wormwood, not lemonade. And his scandalous personal habits made it even worse. For all his brilliance, he was an embarrassment, best forgotten.

At least in his own country.

But in France, Charles Baudelaire had discovered Poe in 1847—at the age of twenty-six—and found in him a kindred spirit, a lost twin. They even looked a little alike, though Poe before the wreckage commenced was the more handsome. The only surviving pictures of Baudelaire show an older, ravaged landscape tinged with a

soupçon

of William Burroughs, but the two men shared bold, swelling foreheads and intense, glowing black eyes.

soupçon

of William Burroughs, but the two men shared bold, swelling foreheads and intense, glowing black eyes.

Starting in 1848, Baudelaire began translating Poe’s tales into French. These translations became a life passion that provided most of his paying literary work for many years. In 1856 some of the stories were collected as

Histoires extraordinaires,

followed in 1857—the same year his own

Les fleurs du mal

was published—by

Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires.

(These titles for the collected Poe translations seem significant in regard to Jules Verne, since the overall title he gave his many novels was

Voyages extraordinaires.

) In 1857 too came

Les Aventures d’Arthur Gordon Pym,

followed by

Eurêka

(1864) and

Histoires grotesques et sérieuses

(1865). They were of such high caliber that they continue to be the standard Poe translations in the world’s French-speaking countries.

Histoires extraordinaires,

followed in 1857—the same year his own

Les fleurs du mal

was published—by

Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires.

(These titles for the collected Poe translations seem significant in regard to Jules Verne, since the overall title he gave his many novels was

Voyages extraordinaires.

) In 1857 too came

Les Aventures d’Arthur Gordon Pym,

followed by

Eurêka

(1864) and

Histoires grotesques et sérieuses

(1865). They were of such high caliber that they continue to be the standard Poe translations in the world’s French-speaking countries.

Why such dedication? In a letter to a friend Baudelaire wrote, with a certain exasperation, “They accuse me, me, of imitating Edgar Poe! Do you know why I so patiently translated Poe?—

Because he resembled me.

The first time that I opened a book of his I saw, with awe and rapture, not only subjects dreamed by me, but

sentences,

thought by me, and written by him, twenty years before.”

31

Because he resembled me.

The first time that I opened a book of his I saw, with awe and rapture, not only subjects dreamed by me, but

sentences,

thought by me, and written by him, twenty years before.”

31

The parallels are striking. Like Poe, Baudelaire suffered familial disruption at an early age. His father, sixty-one at his birth, died when he was six, and little Charles had Mommy all to himself for a couple of years. But then she spoiled everything by marrying a career soldier Baudelaire quickly came to despise. The family moved to Lyon in 1832, and his stepfather promptly dumped Baudelaire into a military boarding school. At fifteen he was permitted to transfer to a prestigious high school. Moody, melancholic, he was expelled in 1839 and then took up the study of law, which primarily meant tireless bohemian carousing in the Latin Quarter. His excesses kept him broke, and it was presumably at this time that he contracted syphilis from a prostitute. In 1841, his parents put him on a boat to India; maybe large doses of sea air and sunshine would bring him to his senses. They didn’t. Reaching the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, he refused to go any farther and returned to Paris. Given all this, it seems remarkable that his stepfather then gave him an inheritance of 100,000 francs, but he did. Baudelaire blew half of it in two years on fancy clothes, fine wines, expensive meals, the right books and paintings, and, the better to enjoy it all, plenty of opium and hashish. His alarmed parents put him on a financial leash with a legal guardian to control his money, which failed to alter his unregenerate habits but left him struggling to get along most of the time, a situation exacerbated by debts to moneylenders that became a pit he never could climb out of—his chronic poverty being something he also shared with Poe.

In 1855, thanks to his growing reputation as a translator of Poe and an art critic, his poetry began to be published. He had great hopes for the 1857 collection of

Les fleurs du mal,

but instead it brought scandal and heartbreak. A scathing review by

Le Figaro

was followed by a trial that found thirteen of the one hundred poems an affront to public morality, heretical, obscene. Six were banned, a suppression not lifted until 1949.

Les fleurs du mal,

but instead it brought scandal and heartbreak. A scathing review by

Le Figaro

was followed by a trial that found thirteen of the one hundred poems an affront to public morality, heretical, obscene. Six were banned, a suppression not lifted until 1949.

The effects of syphilis increasingly showed themselves. He said he felt “the wind of the wing of imbecility” blowing over him. In 1864 he went to Belgium in hopes of persuading a publisher to bring out his complete works, staying there until 1866, when he suffered attacks of paralysis and aphasia. He spent his last year in a nursing home in Paris and died on August 31, 1867, at the age of forty-six, in his mother’s arms.

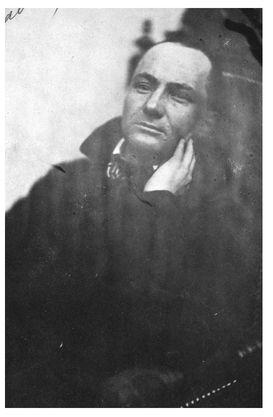

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867). (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource NY Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France)

Poor Baudelaire seems the unlikeliest possible vessel to carry the light of inspiration that would lead to the first best-selling novel about the hollow earth, from Poe to Jules Verne. Compared to tortured visionary Baudelaire, Verne was the picture of bourgeois normalcy. But he read Baudelaire’s translations of Poe in various journals and newspapers (Verne knew almost no English), and they touched something in him. It was, however, something different from the deep solemn chord Poe had sounded in Baudelaire’s heart. Verne responded chiefly to the cleverness, ratiocination, and up-to-date scientific trappings Poe wrapped his strange stories in. Both Poe’s influence and their great differences are glaringly obvious in Verne’s 1897

The Sphinx of the Ice Fields

—his sequel to Poe’s

Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

That he was still thinking about Poe and his chopped-off novel this late in his life (Verne was sixty-seven when it was published) says a lot about how Poe remained with him. But he draws a lame “ending” completely lacking in the grand spiritual mystery Poe’s final paragraphs suggest. Pym’s body is found pasted to a loadstone mountain looming at the South Pole; Verne doesn’t follow him down the cosmic drain clearly waiting in Poe’s original. This is emblematic of a practical materialism very much in the regular daylight world, far from the spooky subterranean cosmos inhabited by Poe.

The Sphinx of the Ice Fields

—his sequel to Poe’s

Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

That he was still thinking about Poe and his chopped-off novel this late in his life (Verne was sixty-seven when it was published) says a lot about how Poe remained with him. But he draws a lame “ending” completely lacking in the grand spiritual mystery Poe’s final paragraphs suggest. Pym’s body is found pasted to a loadstone mountain looming at the South Pole; Verne doesn’t follow him down the cosmic drain clearly waiting in Poe’s original. This is emblematic of a practical materialism very much in the regular daylight world, far from the spooky subterranean cosmos inhabited by Poe.

Verne was just a normal guy whose life gave little hint of the fantastic voyages that he would find within and that would make him the originator of the modern science fiction novel. He was born in 1828 in Nantes, France, then a fading entrepôt thirty-five miles up the Loire River estuary, 240 miles southeast of Paris. His father, Pierre, had a modestly successful law practice, and the family lived in one of the better neighborhoods, in a house overlooking a quay. Verne grew up watching ships coming and going from all over the world. As the firstborn son he was expected to follow his father’s profession. In 1848, his studies took him to Paris, but apolitical young Jules did not join the revolutionary riffraff in the streets. Instead he found himself entranced with the theater. He started hanging out with the artsy bohemian set, actors and writers, becoming friends with Alexandre Dumas

fils,

four years his senior and already famous thanks to his novel

La dame aux camélias,

recently published when they met. They began collaborating on musical confections for the theater, the first of which,

Broken Straws,

went up in June 1850, produced in a venue newly and conveniently opened by Dumas

père.

The play had a decent run, but Verne’s expenses while working on it equaled what money he got.

fils,

four years his senior and already famous thanks to his novel

La dame aux camélias,

recently published when they met. They began collaborating on musical confections for the theater, the first of which,

Broken Straws,

went up in June 1850, produced in a venue newly and conveniently opened by Dumas

père.

The play had a decent run, but Verne’s expenses while working on it equaled what money he got.

Other books

Sensual Confessions by Brenda Jackson

El mensajero by Lois Lowry

Punk'd and Skunked by R.L. Stine

Flesh Factory: An Extreme Horror Novel by Sam West

Shannon by Shara Azod

The Dark Blood of Poppies by Freda Warrington

Love of the Last Tycoon: The Authorized Text (No Series) by Fitzgerald, F. Scott

The Sky Over Lima by Juan Gómez Bárcena

A Vial of Life (A Shade of Vampire #21) by Bella Forrest