Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (24 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

11.77Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

He leaps right into refuting “that dangerous fallacy, the Copernican system”:

Deity, if this be the term employed to designate the Supreme Source of being and activity, cannot be comprehended until the structure and function of the universe are absolutely known; hence mankind is ignorant of God until his handiwork is accurately deciphered. Yet to know God, who, though unknown by the world is not ‘unknowable,’ is the supreme demand of all intellectual research and development.If we accept the logical deduction of the fallacious Copernican system of astronomy, we conclude the universe to be illimitable and incomprehensible, and its cause equally so; therefore, not only would the universe be forever beyond the reach of the intellectual perspective of human aspiration and effort, but God himself would be beyond the pale of our conception, and therefore beyond our adoration.The Koreshan Cosmogony reduces the universe to proportionate limits, and its cause within the comprehension of the human mind. It demonstrates the possibility of the attainment of man to his supreme inheritance, the ultimate dominion of the universe, thus restoring him to the acme of exaltation—the throne of the Eternal, whence he had his origin.

This is sweet, really. Copernicus can’t be true because his theories produce an unfathomable, limitless universe we humans cannot understand; God wouldn’t do that to us because then we couldn’t understand him. Koreshan cosmogony restores us to our true and rightful place—the center of the universe, sitting on the throne of the Eternal, right where we belong. The demotion we all suffered thanks to Copernicus regarding our importance, locationwise, continues to sting. Teed rectified that by returning us to the center of things, albeit inside them. In this regard and others, Koreshanity was deeply conservative.

Next he says that he established the “cosmogonic form” of the universe, which he “declared to be cellular,” determining that the surface of the earth is concave, with an upward curvature of about eight inches to the mile. Even though he ascertained all this with theoretical rigor, still people scoffed. What else for this avatar of “religio-science” to do but conduct experiments proving his theory true? He says, “The suggestion urged itself that we transpose, from the domain of optical science to that of mechanical principles, the effort to enlighten the world as to cosmic form.” The idea was simple. If the earth’s curvature were convex, a straight line extended for any distance would touch at only one point; but if it were concave and the line long enough, it would eventually bump into the upcurving surface. So Professor Morrow invented the Rectilineator. As he described it in

The Cellular Cosmogony:

The Cellular Cosmogony:

The Rectilineator consists of a number of sections in the form of double T squares [|————|], each 12 feet in length, which braced and tensioned cross-arms is to the length of the section, as 1 is to 3. The material of which the sections of the Rectilineator are constructed of inch mahogany, seasoned for twelve years in the shops of the Pullman Palace Co., Pullman, III.

Visitors to the Koreshan State Historic Site can still see a section of it inside Art Hall, sun-bleached and dusty, leaning against the back of the stage. Morrow and some fellow religio-scientists had tried a few tests in Illinois, along the shore of Lake Michigan on the grounds of the Columbian Exposition and on the Illinois & Michigan Canal between the Chicago and Illinois rivers, but neither provided the requisite uninterrupted spaces needed. The plan was to construct a perfectly straight line … four miles long.

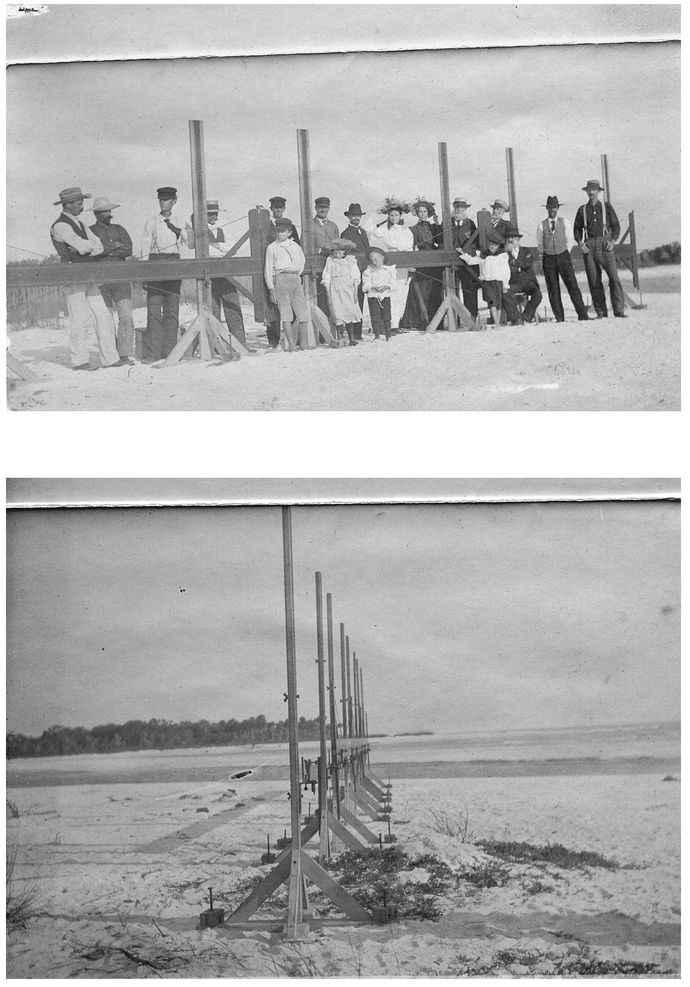

Koreshan experiment involving the Rectilineator. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

This experiment was another reason Estero attracted Teed. Florida’s Gulf Coast then offered endless empty beaches stretching for miles. In January 1897 they began the undertaking near Naples because the coast there offered the needed distance. They set up shop in Naples at a beachfront enclave belonging to Colonel W. N. Haldeman, owner/publisher of the Louisville

Courier Journal,

which says something about Teed’s connections. The Rectilineator sections were transported from Estero in the

Ada,

a small sloop Teed had acquired in 1894. Work on the experiment continued until May. After an “air line” was established, segments of the Rectilineator were meticulously aligned and connected, the trailing section then removed and carefully attached to the front, the lengthy double T square apparatus laboriously hopscotching along the beach while measurements were constantly made. By April 1 they’d gone one mile and by April 16 two, but they took until May 5 to make it another half mile. Elliott Mackle Jr. describes the progress from there:

Courier Journal,

which says something about Teed’s connections. The Rectilineator sections were transported from Estero in the

Ada,

a small sloop Teed had acquired in 1894. Work on the experiment continued until May. After an “air line” was established, segments of the Rectilineator were meticulously aligned and connected, the trailing section then removed and carefully attached to the front, the lengthy double T square apparatus laboriously hopscotching along the beach while measurements were constantly made. By April 1 they’d gone one mile and by April 16 two, but they took until May 5 to make it another half mile. Elliott Mackle Jr. describes the progress from there:

On May 5, another half mile had been covered and the line’s distance from the fixed water line was 54 inches closer than at the beginning, a difference of 4 inches from calculation. At this point, however, the beach curved away and, in any case, the vertical bar of the double T square was within seven inches of the ground, and so it was necessary to employ another method of survey. Using telescopes, poles in the water, and the sloop

Ada

, the line was projected another mile and five-eighths on May 5 and repeated on May 8. Return surveys were performed on May 6 and 11. This projected line met the water four and one-eighth miles from the starting point, indicating to Morrow that the earth’s surface had curved upward 128 inches … the earth had, according to the terms of his experiment, curved upward, proving the validity of the cellular theory.

The care and precise exertion involved were prodigious, although surviving pictures suggest they had fun while they were at it. Needless to say, their efforts were rewarded—as Professor Morrow attests for a dense 140 pages or so in

The Cellular Cosmogony.

They determined the earth’s concavity to their complete—and scientific—satisfaction.

The Cellular Cosmogony.

They determined the earth’s concavity to their complete—and scientific—satisfaction.

Things at Estero sailed along serenely for the next few years except for a couple of blips. The first came from Gustav Damkohler. In 1897 he sued to get his land back. The reasons are a little obscure. He may have believed that Teed promised him a fine house in the community’s center that never materialized. If so, he probably got increasingly peeved as he watched the impressive residence for Teed and Mrs. Ordway (where they would presumably live together in cozy chastity) going up. Damkohler got fed up with Teed and his grandiose plans and took him to court. He found a clever lawyer who used an ingenious gambit—placing the Koreshans’ unconventional beliefs into evidence, essentially trying to get a judgment against them for their odd views.

But Teed understood public relations and from the start had gone out of his way to be sure his Estero community was both friendly and accommodating to its neighbors, especially people in growing Fort Myers, fourteen miles to the north. It paid off. The lengthy trial commenced in April 1897 but was eventually settled out of court. Damkohler got half of his original 320 acres back, but none that affected the Koreshan community.

Koreshan leadership at Estero, probably in the late 1890s, with Cyrus Teed and Mrs. Annie G. Ordway front and center. Note the ceremonial faux medieval halberd bearers on either side.

A considerably more flamboyant attack came the next year, swooping down on them in the form of Editha Lolita, one of the many names and titles she trailed behind her like a long feather boa. According to Rainard, “She claimed to be the Countess Landsfeld, and Baroness Rosenthal, daughter of Ludwig I of Bavaria, and Lola Montez, god child of Pius IX, divorced wife of General Diss Debar, widow of two other men, bride of James Dutton Jackson, and the self-proclaimed successor to the priestess of occultism, Madame Blavatsky.”

51

She showed up in southwestern Florida with current hubby Jackson, whom she’d married in New Orleans on November 13, 1898, her maiden name listed on the official marriage record as Princess Editha Lolita Ludwig. Knowing nothing about him, we would have to suppose James Dutton Jackson a brave man. Editha had come to Florida to establish her own backwoods utopia, the Order of the Crystal Sea, on several thousand acres Jackson apparently owned in Lee County—where they would all live on fruits and nuts (appropriately, Rainard notes), while kicking back to await the millennium. But this was near the Koreshan community, and Editha Lolita decided there wasn’t room for two utopias in one county. She launched into attack mode against Teed and his followers, adroitly using the

Fort Myers Press

as her chief outlet for innuendo and abuse, expressing her shock that a “scoundrel” like Teed could be permitted to live among the decent folk of Fort Myers. “Day after day,” says Rainard, “she reported to the

Fort Myers Press

stories of Teed’s allegedly sordid past.” This went on for months. When the Koreshans decided enough was enough, they revealed to the Fort Myers paper that Editha had been a Koreshan in Chicago but left and then tried to break up the community in ways that had drawn the attention of the police and the Chicago newspapers. In a follow-up story Editha Lolita admitted belonging to the Chicago enclave but had only joined them, as Rainard says, quoting her, “after she had been ‘released by the Jesuit priest’ who had ‘kidnapped her.’” Not long after these revelations, Editha Lolita and her husband faded out of the picture, heading on to greener delusional pastures elsewhere.

51

She showed up in southwestern Florida with current hubby Jackson, whom she’d married in New Orleans on November 13, 1898, her maiden name listed on the official marriage record as Princess Editha Lolita Ludwig. Knowing nothing about him, we would have to suppose James Dutton Jackson a brave man. Editha had come to Florida to establish her own backwoods utopia, the Order of the Crystal Sea, on several thousand acres Jackson apparently owned in Lee County—where they would all live on fruits and nuts (appropriately, Rainard notes), while kicking back to await the millennium. But this was near the Koreshan community, and Editha Lolita decided there wasn’t room for two utopias in one county. She launched into attack mode against Teed and his followers, adroitly using the

Fort Myers Press

as her chief outlet for innuendo and abuse, expressing her shock that a “scoundrel” like Teed could be permitted to live among the decent folk of Fort Myers. “Day after day,” says Rainard, “she reported to the

Fort Myers Press

stories of Teed’s allegedly sordid past.” This went on for months. When the Koreshans decided enough was enough, they revealed to the Fort Myers paper that Editha had been a Koreshan in Chicago but left and then tried to break up the community in ways that had drawn the attention of the police and the Chicago newspapers. In a follow-up story Editha Lolita admitted belonging to the Chicago enclave but had only joined them, as Rainard says, quoting her, “after she had been ‘released by the Jesuit priest’ who had ‘kidnapped her.’” Not long after these revelations, Editha Lolita and her husband faded out of the picture, heading on to greener delusional pastures elsewhere.

Estero was calm as the new century began. Its population dropped to twenty-eight at one point, in part because Teed had returned to Chicago to begin closing out the operation there, while his esteemed counterpart, Victoria Gratia, was in Washington, DC, helping set up a new Koreshan colony in the heart of the beast. The last of the Chicago crowd moved lock, stock, and fifteen railway cars full of stuff to Florida in 1903, raising the population to around two hundred—hardly 10 million, but not bad. Everything was peachy at Estero until 1904 or so. Their various enterprises were humming along, and all was going so well that Teed decided to incorporate as a town, mainly because it would qualify them for tax money to improve the roads. This first step into the local political realm proved to be the beginning of the end. Non-Koreshans in the lightly populated county were understandably apprehensive about the influence of this relatively large group of people, all of whom were pledged to vote in a bloc. Pronouncements such as “I am going to bring thousands to Florida … and make every vote count in Florida and Lee County,” reported in the increasingly hostile

Fort Myers Press,

didn’t help. Also, Fort Myers—or at least the newspaper—began feeling it might have more to lose after the railroad was extended there in 1904, and dream balloons of great growth and prosperity began inflating. They didn’t want a bunch of crazy hollow earthers spoiling their prospects.

Fort Myers Press,

didn’t help. Also, Fort Myers—or at least the newspaper—began feeling it might have more to lose after the railroad was extended there in 1904, and dream balloons of great growth and prosperity began inflating. They didn’t want a bunch of crazy hollow earthers spoiling their prospects.

The editor of the

Fort Myers Press,

Philip Isaacs, played a major part in what followed. He had political ambitions and offered Koreshans a weekly news column (written by Rectilineator inventor U. G. Morrow) in exchange for a pledge to vote for him for county judge in the 1904 Democratic primary and general election. They kept their end of the bargain, and he was elected. This was back in the heyday of the “solid South,” meaning solidly Democratic. But the election of 1906 proved more troublesome. It became known that in 1904 the Koreshans had defected from the Democratic party and voted as a group for Teddy Roosevelt, though he was the only Republican they voted for. This peeved local Democrats, who came up with a scam to bar them from voting in the 1906 Democratic primary—a pledge each voter was required to sign affirming that he had supported all Democratic candidates in 1904. The Koreshans, not easily scared off, simply amended the pledge before signing it and voted anyway.

Fort Myers Press,

Philip Isaacs, played a major part in what followed. He had political ambitions and offered Koreshans a weekly news column (written by Rectilineator inventor U. G. Morrow) in exchange for a pledge to vote for him for county judge in the 1904 Democratic primary and general election. They kept their end of the bargain, and he was elected. This was back in the heyday of the “solid South,” meaning solidly Democratic. But the election of 1906 proved more troublesome. It became known that in 1904 the Koreshans had defected from the Democratic party and voted as a group for Teddy Roosevelt, though he was the only Republican they voted for. This peeved local Democrats, who came up with a scam to bar them from voting in the 1906 Democratic primary—a pledge each voter was required to sign affirming that he had supported all Democratic candidates in 1904. The Koreshans, not easily scared off, simply amended the pledge before signing it and voted anyway.

Other books

Quarter Square by David Bridger

Sin destino by Imre Kertész

The Widow of the South by Robert Hicks

Once a Warrior by Karyn Monk

The Witch & the Cathedral - Wizard of Yurt - 4 by C. Dale Brittain

Encyclopedia Brown and the Case of the Treasure Hunt by Donald J. Sobol

The Parliament House by Edward Marston

All Those Vanished Engines by Paul Park

Hex and the Single Witch by Saranna Dewylde