Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (28 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

4.52Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

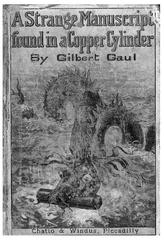

Published anonymously in 1888,

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder

is an example of a creeping sameness in hollow earth novels of the time. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct warmed-over hollow earth stew, including the requisite sea monster shown here on the cover of a pirated British edition.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder

is an example of a creeping sameness in hollow earth novels of the time. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct warmed-over hollow earth stew, including the requisite sea monster shown here on the cover of a pirated British edition.

Let’s look at a small sample of the titles.

The opening sections of

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder,

published anonymously in 1888, exemplify the creeping sameness. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct a warmed-over hollow earth stew. Adam More (Adam Seaborn was Symmes’ hero, you will remember; and More wrote the first

Utopia

), shipwrecked with a companion in the Southern Ocean, lands on an island peopled by ferocious black cannibals who promptly eat his pal. More escapes on a small boat, drawn ever southward by a strong current until his craft is sucked downward into a black tunnel and pops up in a calm, warm sea lapping against a paradisiacal countryside. Here the author reaches even farther back in his ransacking, giving us a turned-on-its-head society that seems inspired by those in

Niels Klim.

As Steve Trussel summarizes the action,

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder,

published anonymously in 1888, exemplify the creeping sameness. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct a warmed-over hollow earth stew. Adam More (Adam Seaborn was Symmes’ hero, you will remember; and More wrote the first

Utopia

), shipwrecked with a companion in the Southern Ocean, lands on an island peopled by ferocious black cannibals who promptly eat his pal. More escapes on a small boat, drawn ever southward by a strong current until his craft is sucked downward into a black tunnel and pops up in a calm, warm sea lapping against a paradisiacal countryside. Here the author reaches even farther back in his ransacking, giving us a turned-on-its-head society that seems inspired by those in

Niels Klim.

As Steve Trussel summarizes the action,

Upon landing, he finds a strange race very much resembling Arabs. They take him to their underground city, where he is taught a language similar to Arabic by the beautiful Almah, and discovers that the cultural and moral values of this peculiar race are weirdly inverted. These pseudo-Arabs see better in the dark than in daylight. They seek poverty, giving their possessions to whomever will take them; they long for death as the highest blessing of their lives; and, although peaceful, they practice human sacrifice on hundreds of willing victims. Adam and Almah fall in love, and find that they are destined to be given the honor of dying for her people. At the last moment, More kills several of the populace with his rifle, and the multitudes, awe-stricken, fall down and worship him as a god who can bring the greatest good—death—instantly.

59

This novel is at best an orientally embroidered celebration of life over death, an exotic romance without much redeeming value. Perhaps most interesting is that this story appeared serially in nineteen installments in one of the most popular American magazines of the time—

Harper’s Weekly

(which billed itself as “A Journal of Civilization”)—an indicator of how mainstream the idea of the hollow earth had become. The anonymous author turned out to be a Canadian college professor named James de Mille (1833–1880), a prolific and popular novelist in his day. He’s pretty much forgotten now, though he lives on in Ph.D. dissertations and academic criticism, and a surprising number of his novels are available online as e-texts.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder,

published posthumously, is considered the first Canadian science fiction novel and was reprinted by Insomniac Press in 2001.

Harper’s Weekly

(which billed itself as “A Journal of Civilization”)—an indicator of how mainstream the idea of the hollow earth had become. The anonymous author turned out to be a Canadian college professor named James de Mille (1833–1880), a prolific and popular novelist in his day. He’s pretty much forgotten now, though he lives on in Ph.D. dissertations and academic criticism, and a surprising number of his novels are available online as e-texts.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder,

published posthumously, is considered the first Canadian science fiction novel and was reprinted by Insomniac Press in 2001.

William R. Bradshaw (1851–1927) wrote

The Goddess of Atvatabar,

first published in 1892. This hollow earth novel has an almost overwhelming sumptuousness and richness of detail. An Irish immigrant who settled in Flushing, New York, Bradshaw was a regular contributor to magazines, edited

Literary Life

and

Decorator and Furnisher,

and was associated with

Field and Stream

as well. At his death in 1927 he was a Republican district captain in Flushing and president of the New York Anti-Vivisection Society.

The Goddess of Atvatabar,

first published in 1892. This hollow earth novel has an almost overwhelming sumptuousness and richness of detail. An Irish immigrant who settled in Flushing, New York, Bradshaw was a regular contributor to magazines, edited

Literary Life

and

Decorator and Furnisher,

and was associated with

Field and Stream

as well. At his death in 1927 he was a Republican district captain in Flushing and president of the New York Anti-Vivisection Society.

A number of new elements show themselves here. One is revealed in the full title:

THEGODDESS OF ATVATABARBEING THEHISTORY OF THE DISCOVERYOF THEINTERIOR WORLDANDCONQUEST OF ATVATABAR

Earlier hollow earth novels such as

Symzonia

had land-grabbing imperialism as a subtext, but here it is announced blazing right in the title. This novel came at a time when America was running out of open land and the easy promise (seldom realized) of riches on the frontier. What had been called Seward’s Folly—the vast tract of Alaska purchased from Russia in 1867—was looking visionary by the end of the century. And 1892 was just a few years before American policy changed to engage in a little empire building in the form of the Spanish-American War, which on slim excuse not only kicked Spain out of the New World but occupied the Philippines as well. So the conquest of Atvatabar is imaginatively predictive of geopolitical forces starting to simmer in the real world.

Symzonia

had land-grabbing imperialism as a subtext, but here it is announced blazing right in the title. This novel came at a time when America was running out of open land and the easy promise (seldom realized) of riches on the frontier. What had been called Seward’s Folly—the vast tract of Alaska purchased from Russia in 1867—was looking visionary by the end of the century. And 1892 was just a few years before American policy changed to engage in a little empire building in the form of the Spanish-American War, which on slim excuse not only kicked Spain out of the New World but occupied the Philippines as well. So the conquest of Atvatabar is imaginatively predictive of geopolitical forces starting to simmer in the real world.

And wouldn’t you know it? The name of the narrator/hero/chief conqueror is Commander Lexington

White.

The story opens aboard the

Polar King,

with White and his crew on a mission to discover the North Pole—something very much in the news at the time. Even as Bradshaw was writing, Admiral Robert Peary was making his second expedition to Greenland, a prelude to the one that would take him successfully to the pole on April 6, 1909—or so he believed and claimed. Toward the end of the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth, the idea of reaching the pole became a sort of frenzy, with explorer after explorer obsessed with gaining the dubious “glory” of being the first to do so. Just as Poe had tried to cash in on a polar mania fifty years earlier, Bradshaw’s polar framing for his hollow earth novel was quite timely.

White.

The story opens aboard the

Polar King,

with White and his crew on a mission to discover the North Pole—something very much in the news at the time. Even as Bradshaw was writing, Admiral Robert Peary was making his second expedition to Greenland, a prelude to the one that would take him successfully to the pole on April 6, 1909—or so he believed and claimed. Toward the end of the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth, the idea of reaching the pole became a sort of frenzy, with explorer after explorer obsessed with gaining the dubious “glory” of being the first to do so. Just as Poe had tried to cash in on a polar mania fifty years earlier, Bradshaw’s polar framing for his hollow earth novel was quite timely.

On the

Polar King,

frustrated at trying to find an opening in the ring of polar ice, they fire one of their powerful guns containing shells of “terrorite” at it—a supergunpowder of White’s invention—cleaving the mountain of ice and creating a narrow passage to, yes, the open polar sea lying beyond. As they sail into it, White reflects, “I was romantic, idealistic. I loved the marvelous, the magnificent, and the mysterious … I wished to discover all that was weird and wonderful on the earth.” And does his wish ever come true.

Polar King,

frustrated at trying to find an opening in the ring of polar ice, they fire one of their powerful guns containing shells of “terrorite” at it—a supergunpowder of White’s invention—cleaving the mountain of ice and creating a narrow passage to, yes, the open polar sea lying beyond. As they sail into it, White reflects, “I was romantic, idealistic. I loved the marvelous, the magnificent, and the mysterious … I wished to discover all that was weird and wonderful on the earth.” And does his wish ever come true.

White says he became absorbed in this polar quest after learning about the failure of a recent expedition whose ship was frozen in at Smith’s Sound in Baffin Bay, but had tried for the pole in a “monster balloon,” failing when the balloon’s car smashed into an iceberg. This reminded him of “the ill-fated Sir John Franklin and

Jeannette

expeditions,” which in turn led him to read “almost every narrative of polar discovery” and to converse “with Arctic navigators both in England and the United States.” His polar homework fits neatly into a tradition of hollow earth novels going back to Symmes and Poe. He says he found it strange that modern sailors “could only get three degrees nearer the pole than Henry Hudson did nearly three hundred years ago,” and when his father opportunely dies and leaves him a huge fortune, he decides to try for the pole. He builds the

Polar King

according to his own advanced specs, one being a handy device also of his own invention, an “apparatus that both heated the ship and condensed the sea water for consumption on board ship and for feeding the boilers.” As he’s listing the other provisioning details, the first hint of the novel’s deep eccentricity appears. Along with “the usual Arctic outfit to withstand the terrible climate of high latitudes,” White has a special item of clothing made for all:

Jeannette

expeditions,” which in turn led him to read “almost every narrative of polar discovery” and to converse “with Arctic navigators both in England and the United States.” His polar homework fits neatly into a tradition of hollow earth novels going back to Symmes and Poe. He says he found it strange that modern sailors “could only get three degrees nearer the pole than Henry Hudson did nearly three hundred years ago,” and when his father opportunely dies and leaves him a huge fortune, he decides to try for the pole. He builds the

Polar King

according to his own advanced specs, one being a handy device also of his own invention, an “apparatus that both heated the ship and condensed the sea water for consumption on board ship and for feeding the boilers.” As he’s listing the other provisioning details, the first hint of the novel’s deep eccentricity appears. Along with “the usual Arctic outfit to withstand the terrible climate of high latitudes,” White has a special item of clothing made for all:

Believing in the absolute certainty of discovering the pole and our consequent fame, I had included in the ship’s stores a special triumphal outfit for both officers and sailors. This consisted of a Viking helmet of polished brass surmounted by the figure of a silver-plated polar bear, to be worn by both officers and sailors. Each officer and sailor was armed with a cutlass having the figure of a polar bear in silver-plated brass surmounting the hilt.

White sets out with his ace crew, not via Greenland and Baffin Bay as so many had before him, but through the Bering Straits, despite the

Jeannette

expedition’s horrific experiences while attempting the same route.

60

They encounter the open polar sea and the usual abundance of wildlife up there, and at last Professor Starbottle, the chief scientist aboard, proclaims, “I am afraid, Commander, we will never reach the pole … we are falling into the interior of the earth!” After predictable shouts of “Turn back the ship!” the pilot observes that they are still sailing along nicely. “If the earth is a hollow shell having a subterranean ocean, we can sail thereon bottom upward and masts downward, just as easily as we sail on the surface of the ocean here.” Here, as in other hollow earth novels, ideas of gravity are conveniently cockeyed. They press on into the polar opening. “The prow of the

Polar King

was pointed directly toward the darkness before us, toward the centre of the earth.” A dozen of the more fearful sailors are permitted to take a boat and head back where they came from.

Jeannette

expedition’s horrific experiences while attempting the same route.

60

They encounter the open polar sea and the usual abundance of wildlife up there, and at last Professor Starbottle, the chief scientist aboard, proclaims, “I am afraid, Commander, we will never reach the pole … we are falling into the interior of the earth!” After predictable shouts of “Turn back the ship!” the pilot observes that they are still sailing along nicely. “If the earth is a hollow shell having a subterranean ocean, we can sail thereon bottom upward and masts downward, just as easily as we sail on the surface of the ocean here.” Here, as in other hollow earth novels, ideas of gravity are conveniently cockeyed. They press on into the polar opening. “The prow of the

Polar King

was pointed directly toward the darkness before us, toward the centre of the earth.” A dozen of the more fearful sailors are permitted to take a boat and head back where they came from.

About 250 miles down into the abyss they begin to experience lessened gravity, while getting their first glimpse of “an orb of rosy flame”—Swang, the inner earth sun. Professor Starbottle exclaims, surveying the scene with his telescope, “The whole interior planet is covered with continents and oceans just like the outer sphere!”

“‘We have discovered El Dorado,’ said the Captain.”

“‘The heaviest elements fall to the centre of all spheres,’ said Professor Goldrock. ‘I am certain we shall discover mountains of gold ere we return.’” Ideas of profit never lag far behind the excitement of discovery.

A storm comes up after a week’s subterranean sailing, providing the first real taste of the sensuous detail to come:

The sun grew dark and appeared like a disc of sombre gold. The ocean was lashed by a furious hurricane into incredible mountains of water. Every crest of the waves seemed a mass of yellow flame. The internal heavens were rent open with gulfs of sulphur-colored fire … a golden-yellow phosphorescence covered the ocean. The water boiled in maddening eddies of lemon-colored seas, while from the hurricane decks streamed cataracts of saffron fire. The lightning, like streaks of molten gold, hurled its burning darts into the sea. Everything bore the glow of amber-colored fire.

There is a sumptuous, painterly quality to the writing throughout the book. This is a hollow earth paradise of exquisite detail described in exquisite detail, literally reveling in it, though after a while it almost becomes overwhelming, like one too many bites of a thirteen-layer German chocolate cake. This hyperestheti-cism is part of

Atvatabar’s

larger purpose—to show a society as devoted to art and spirituality as most are to profit and power. It’s as if Bradshaw is straining to take the visual ideas and aesthetics of newly developing art nouveau—a style that had just come along in the 1880s, breaking with classicism, emphasizing rich organic qualities—and render them in prose. One goal of art nouveau (which had its origins in the 1860s with William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement) was to integrate beauty into everyday life, to make people’s lives better by greater exposure to it, and this is a main pillar of the civilization White & Co. encounter—before they begin crashing around in it ruining everything, anyway.

Atvatabar’s

larger purpose—to show a society as devoted to art and spirituality as most are to profit and power. It’s as if Bradshaw is straining to take the visual ideas and aesthetics of newly developing art nouveau—a style that had just come along in the 1880s, breaking with classicism, emphasizing rich organic qualities—and render them in prose. One goal of art nouveau (which had its origins in the 1860s with William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement) was to integrate beauty into everyday life, to make people’s lives better by greater exposure to it, and this is a main pillar of the civilization White & Co. encounter—before they begin crashing around in it ruining everything, anyway.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son, Julian, wrote the introduction to

The Goddess of Atvatabar,

in which he raves about the novel as a fine example of portraying the “ideal” in fiction, taking the opportunity to beat such “realists” as Zola and Tolstoy about the head and shoulders and claiming that their day has come and gone—a singularly wrongheaded judgment that served his own writerly purposes. Like Bradshaw’s novel, Julian Hawthorne’s fiction chiefly dealt with the fantastic and the supernatural. After citing Symmes, Verne, and Bulwer-Lytton’s

The Coming Race

—proof he’s done his hollow earth homework—Hawthorne declares that Bradshaw “has not fallen below the highest standard that has been erected by previous writers,” and in fact “has achieved a work of art which may rightfully be termed great.” It’s actually superior to Verne, who, “in composing a similar story, would stop short with a description of mere physical adventure.” Bradshaw goes beyond this, creating “in conjunction therewith an interior world of the soul, illuminated with the still more dazzling sun of ideal love in all its passion and beauty.” This world of the soul lies at

Atvatabar’s

core:

The Goddess of Atvatabar,

in which he raves about the novel as a fine example of portraying the “ideal” in fiction, taking the opportunity to beat such “realists” as Zola and Tolstoy about the head and shoulders and claiming that their day has come and gone—a singularly wrongheaded judgment that served his own writerly purposes. Like Bradshaw’s novel, Julian Hawthorne’s fiction chiefly dealt with the fantastic and the supernatural. After citing Symmes, Verne, and Bulwer-Lytton’s

The Coming Race

—proof he’s done his hollow earth homework—Hawthorne declares that Bradshaw “has not fallen below the highest standard that has been erected by previous writers,” and in fact “has achieved a work of art which may rightfully be termed great.” It’s actually superior to Verne, who, “in composing a similar story, would stop short with a description of mere physical adventure.” Bradshaw goes beyond this, creating “in conjunction therewith an interior world of the soul, illuminated with the still more dazzling sun of ideal love in all its passion and beauty.” This world of the soul lies at

Atvatabar’s

core:

The religion of the new race is based upon the worship of the human soul, whose powers have been developed to a height unthought of by our section of mankind, although on lines the commencement of which are already within our view. The magical achievements of theosophy and occultism, as well as the ultimate achievements of orthodox science, are revealed in their most amazing manifestations, and with a sobriety and minuteness of treatment that fully satisfies what may be called the transcendental reader.

Other books

Wind in the Wires by Joy Dettman

A Flower’s Shade by Ye Zhaoyan

Flesh Wounds by Brookmyre, Chris

Hunted (A Cyn & Raphael Novella) by D.B. Reynolds,

Shadow of the Gallows by Steven Grey

The Cataclysm by Weis, Margaret, Hickman, Tracy

Blackout by Gianluca Morozzi

Deadly Is the Night by Dusty Richards

The Israel Bond Omnibus by Sol Weinstein