Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (31 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

9.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

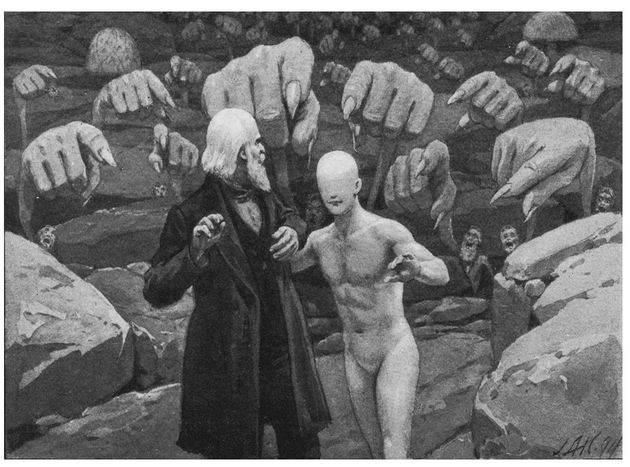

(above) The subterranean pilgrim in

Etidorhpa

visits a mushroom forest (top); and tiny tormented people (bottom).

Etidorhpa

visits a mushroom forest (top); and tiny tormented people (bottom).

Abruptly he’s borne aloft by one of the huge hands and carried to a stone platform in the center of the cavern. Amid the grotesques, a handsome man appears to him, insisting he’s a friend, a deliverer, saying that all the deformities he’s seeing aren’t real, are produced in his imagination by the influence of an evil spirit (his guide), they’re really happy normal people. “They seek to save you from disaster. One hour of experience such as they enjoy is worth a hundred years of the pleasures known to you. After you have partaken of their exquisite joy, I will conduct you back to the earth’s surface whenever you desire to leave us.” Drink this! Tempted, the narrator begins to drink but then dashes the cup on a rock. Suddenly the twisted creatures and the handsome persuader vanish. Slowly they are replaced by beautiful vocal and instrumental music. And “by and by, from the corridors of the cavern, troops of bright female forms floated into view. Never before had I seen such loveliness in human mold.”

The following scene could have been choreographed by Busby Berkeley on acid.

Carrying “curious musical instruments and beautiful wands, they produced a scenic effect of rare beauty that the most extravagant dream of fairyland could not surpass. The great hall was clothed in brilliant colors. Flags and streamers fluttered in breezes that also moved the garments of the angelic throng about me.” They begin to dance around him to “music indescribable,” group after group of them, each singing “sweeter songs, more beautiful, and richer in dress than those preceding.” The narrator nearly swoons in ecstasy. “I was rapt, I became a thrill of joy. A single moment of existence such as I experienced, seemed worth an age of any other pleasure.”

Can he get any higher? Yes. The music ceases and Etidorhpa herself appears. “She stood before me, slender, lithe, symmetrical, radiant. Her face paled the beauty of all who preceded her.” She announces that “love rules the world, and I am the Soul of Love Supreme”—and that he can have her all to himself forever. She and her beautiful minions have appeared to him as a preview of things to come. But first he must undergo a few more trials. “You can not pass into the land of Etidorhpa until you have suffered as only the damned can suffer,” she says, offering him a cup filled with green liquid. Again, he almost drinks but dashes that cup to the floor too. Etidorhpa disappears along with all the chorus girls. The narrator finds himself back on the surface, surrounded by endless desert sand. For days he struggles along in the fiery heat, without food or drink. He’s dying of thirst when he encounters a caravan whose leader offers a lifesaving glass of clear green liquid. “No. I will not drink.” The caravan abruptly vanishes, and a cool, refreshing breeze begins to blow. Soon he is nearly freezing, and days pass without number. He curses God and prays for death. He wishes he’d given in to one of the tempters—but then, no. “I have faith in Etidorhpa, and were it to do over again I would not drink.”

The magic words! Suddenly he is once again back in the cavern with his guide. It’s all been a brief hallucination, occurring in the moment after he sipped the magic mushroom cocktail. Their journey continues, literally downhill for them and for the reader as well. They get to the end of a shelf of rock overhanging an unfathomable abyss—the enormous hollow center of the earth—and his guide bids the narrator to jump. Are you crazy? he asks. The guide says that here lies Enlightenment, grabs him, and they leap into nothingness. Instead of falling, they seem to float, and after a time they reach the very center, “the Sphere of Rest.” Here the narrator experiences a midair satori. “Perfect rest came over my troubled spirit. All thoughts of former times vanished. The cares of life faded; misery, distress, hatred, envy, jealousy, and unholy passions, were blotted from existence. I had reached the land of Etidorhpa—THE END OF THE EARTH.”

He’s achieved a moment of spiritual awakening. His guide tells him:

It has been my duty to crush, to overcome by successive lessons your obedience to your dogmatic, materialistic earth philosophy, and bring your mind to comprehend that life on earth’s surface is only a step towards a higher existence, which may, when selfishness is conquered, in a time to come, be gained by mortal man, and while he is in the flesh. The vicissitudes through which you have recently passed should be to you an impressive lesson, but the future holds for you a lesson far more important, the knowledge of spiritual, or mental evolution which men may yet approach; but that I would not presume to indicate now, even to you.

He stands on the edge of “The Unknown Country”—but cannot reveal what comes next. It would be too mind-blowing for mere mortals. And so ends the novel’s action.

Etidorhpa

is horribly flawed as novels go—I’ve left out the frequent long tedious asides in which Lloyd challenges the writer of the manuscript about seemingly impossible aspects of his story, which he then explains/defends at “scientific” and philosophical length. But it is certainly a landmark departure from the usual hollow earth novels, using the conceit not for mere adventure, or as the device for concocting some new sociopolitical utopia. The utopia it presents, if it can be called that, is purely spiritual—however deeply weird.

is horribly flawed as novels go—I’ve left out the frequent long tedious asides in which Lloyd challenges the writer of the manuscript about seemingly impossible aspects of his story, which he then explains/defends at “scientific” and philosophical length. But it is certainly a landmark departure from the usual hollow earth novels, using the conceit not for mere adventure, or as the device for concocting some new sociopolitical utopia. The utopia it presents, if it can be called that, is purely spiritual—however deeply weird.

Arguably the most boring hollow earth novel ever, in a couple of respects, is Clement Fezandie’s

Through the Earth

(1898). Fezandie (1865–1959) was a math teacher in New York City and eventually wrote science fiction for Hugo Gernsback (1884–1967), the pioneering editor who invented sci-fi magazines, starting with

Amazing Stories

in 1926.

Through the Earth

qualifies only marginally as a hollow earth novel. It tells of a project to bore a tunnel between New York City and Australia to carry goods and people between the two places, like the world’s longest freight elevator. Most of the book is occupied by an account of the first test ride, essayed by a brave impoverished lad for the prize money of £100 (offered because no one was willing to try it for free). As he plunges through the tube, he relates scientific observations of gravity, temperature, and distance. At the end, the tunnel self-destructs, but the plucky volunteer lives through it, sells his story to a New York newspaper for $100,000, tours the country as a celebrated hero, and marries the inventor’s pretty daughter. Horatio Alger meets the hollow earth. But it’s another example of how writers of every period have used the notion for purposes appropriate to their time. The first attempts at building subways went back to the 1840s in London, where underground railways were first pioneered, but by the turn of the new century a certain mania for subway building was taking place in major cities worldwide. The first practical subway line in the United States was under construction in Boston while Fezandie was writing

Through the Earth,

as was New York’s (which would officially open in 1904), and it seems likely that Fezandie simply used these as a jumping-off point. Why not a really

long

one?

Through the Earth

(1898). Fezandie (1865–1959) was a math teacher in New York City and eventually wrote science fiction for Hugo Gernsback (1884–1967), the pioneering editor who invented sci-fi magazines, starting with

Amazing Stories

in 1926.

Through the Earth

qualifies only marginally as a hollow earth novel. It tells of a project to bore a tunnel between New York City and Australia to carry goods and people between the two places, like the world’s longest freight elevator. Most of the book is occupied by an account of the first test ride, essayed by a brave impoverished lad for the prize money of £100 (offered because no one was willing to try it for free). As he plunges through the tube, he relates scientific observations of gravity, temperature, and distance. At the end, the tunnel self-destructs, but the plucky volunteer lives through it, sells his story to a New York newspaper for $100,000, tours the country as a celebrated hero, and marries the inventor’s pretty daughter. Horatio Alger meets the hollow earth. But it’s another example of how writers of every period have used the notion for purposes appropriate to their time. The first attempts at building subways went back to the 1840s in London, where underground railways were first pioneered, but by the turn of the new century a certain mania for subway building was taking place in major cities worldwide. The first practical subway line in the United States was under construction in Boston while Fezandie was writing

Through the Earth,

as was New York’s (which would officially open in 1904), and it seems likely that Fezandie simply used these as a jumping-off point. Why not a really

long

one?

The Secret of the Earth

by Charles Beale (1899) features two characters who have invented an airplane that they fly to the North Pole and into a Symmes’ Hole into the interior. They find a paradise that was mankind’s first home and then fly out through the hole in the South Pole. Their airship beats the Wright Brothers by four years, of course, but in the 1890s, trying to come up with one was all the rage with inventors. It’s often forgotten that the Wrights had serious competitors racing with them to develop a reliable design, and that one incentive was a large cash prize offered by France to the inventor of the first one that really worked—which is to say that the

idea

of airplanes was, well, in the air at the time Beale’s

Secret of the Earth

appeared.

by Charles Beale (1899) features two characters who have invented an airplane that they fly to the North Pole and into a Symmes’ Hole into the interior. They find a paradise that was mankind’s first home and then fly out through the hole in the South Pole. Their airship beats the Wright Brothers by four years, of course, but in the 1890s, trying to come up with one was all the rage with inventors. It’s often forgotten that the Wrights had serious competitors racing with them to develop a reliable design, and that one incentive was a large cash prize offered by France to the inventor of the first one that really worked—which is to say that the

idea

of airplanes was, well, in the air at the time Beale’s

Secret of the Earth

appeared.

William Alexander Taylor’s

Intermere

(1901) is like a bad rewrite of

Symzonia.

It too uses the hollow earth as a vehicle for current ideas. This otherworldly society has solved all earthly problems. It is a perfect democracy—almost. Women are supposedly equal, but their “chosen” role is generally that of housewife, and those who work don’t make as much money as men. They receive five fewer years of education than men do, and they’re not allowed to own real estate. But everybody’s pretty and handsome, nobody’s poor, there’s a four-hour workday, the communities are lovely and idyllic, crops go from planting to harvest in ten days, all marriages are happy and harmonious, and the food is fabulous but nobody has to cook. They have Medocars, Aerocars, and Merocars—autos, airplanes, and ships—which zip silently about at “a rate of speed that makes our limited railway trains seem like lumbering farm wagons.” They are powered by a force derived from electricity, which proves to be the secret behind their social and economic perfection.

Intermere

(1901) is like a bad rewrite of

Symzonia.

It too uses the hollow earth as a vehicle for current ideas. This otherworldly society has solved all earthly problems. It is a perfect democracy—almost. Women are supposedly equal, but their “chosen” role is generally that of housewife, and those who work don’t make as much money as men. They receive five fewer years of education than men do, and they’re not allowed to own real estate. But everybody’s pretty and handsome, nobody’s poor, there’s a four-hour workday, the communities are lovely and idyllic, crops go from planting to harvest in ten days, all marriages are happy and harmonious, and the food is fabulous but nobody has to cook. They have Medocars, Aerocars, and Merocars—autos, airplanes, and ships—which zip silently about at “a rate of speed that makes our limited railway trains seem like lumbering farm wagons.” They are powered by a force derived from electricity, which proves to be the secret behind their social and economic perfection.

The Intermerans also have a device that’s rather like an online fax machine. When the displaced narrator asks for news from home, his host goes to a cabinet and opens it: “Soon his hands began to move with rhythmic rapidity over the curiously inlaid center of the flat surface of the open cabinets. At the end of ten or fifteen minutes his manipulations ceased, a compartment noiselessly opened, and eight beautifully printed pages, four by six inches, bound in the form of a booklet, fell upon the table. The pages before me comprised a compendium of yesterday’s doings of the entire world.” In their opinion, surface events, which they keep close track of, are really stupid. “Selfishness, oppression, slaughter, pride, conquest, greed, vanity, self-adulation and base passions make up ninety-nine one-hundredths of this record,” sighs the host. This leads him into a tirade against surface world newspapers. He says this objective compendium “is to promote wisdom. The newspaper [exists] to feed vicious or depraved appetite, as well as to convey useful information. This is the cold, colorless, passionless record of facts and information, from which knowledge and wisdom may be deduced to some extent. Your newspaper is the opposite, taken in its entirety. It consists of the inextricable mingling together of the good and the bad, of the useful and the useless, and the elevating and the degrading, the latter always in the ascendant.”

Sounds like he’s been reading the papers, all right. In fact, this critique comes from someone who spent much of his career

writing

them. Taylor was an Ohio lawyer born in 1837 who turned to newspaper work in 1858, and was associated with various papers (chiefly the

Cincinnati Enquirer)

until 1900. So he knew the failings of American newspapers from the inside.

writing

them. Taylor was an Ohio lawyer born in 1837 who turned to newspaper work in 1858, and was associated with various papers (chiefly the

Cincinnati Enquirer)

until 1900. So he knew the failings of American newspapers from the inside.

Gabriel de Tarde’s

Underground Man,

first published in 1896, appeared in English translation in 1905 with a preface by H. G. Wells. This hollow earth novel by a French sociologist set in the thirty-first century is a satire on prevailing sociological thinking. It tells the story of how a near-utopia had been created on the surface, until the sun began sputtering out and dying, killing nearly all of mankind. Those remaining are driven beneath the surface, where they establish yet another utopia, bristling with thoroughly modern machines and techniques: thermal power, electric trains, monocyles, and other gizmos. But the main idea is that being driven underground has “produced, so to say, a purificaton of society.” It has, in effect, changed human nature. He writes:

Underground Man,

first published in 1896, appeared in English translation in 1905 with a preface by H. G. Wells. This hollow earth novel by a French sociologist set in the thirty-first century is a satire on prevailing sociological thinking. It tells the story of how a near-utopia had been created on the surface, until the sun began sputtering out and dying, killing nearly all of mankind. Those remaining are driven beneath the surface, where they establish yet another utopia, bristling with thoroughly modern machines and techniques: thermal power, electric trains, monocyles, and other gizmos. But the main idea is that being driven underground has “produced, so to say, a purificaton of society.” It has, in effect, changed human nature. He writes:

Secluded thus from every influence of the natural milieu into which it was hitherto plunged and confined, the social milieu was for the first time able to reveal and display its true virtues, and the real social bond appeared in all its vigor and purity. It might be said that destiny had desired to make in our case an extended sociological experiment for its own edification by placing us in such extraordinarily unique conditions…. The mental space left by the reduction of our needs is taken up by those talents—artistic, poetic, and scientific—which multiply and take deep root. They become the true needs of society. They spring from a necessity to produce and not from a necessity to consume.

Worth noting is that this perfect society has been produced by “the complete elimination of living nature, whether animal or vegetable, man only excepted.” This idea of completely overcoming nature, subduing and totally dominating it, was one that had been growing during the nineteenth century. And how could it not, given the ceaseless succession of scientific and technical marvels that just kept unfolding? So in

Underground Man

de Tarde pushes such hubris to the limits, by getting rid of nature entirely!

Underground Man

de Tarde pushes such hubris to the limits, by getting rid of nature entirely!

Other books

One You Never Leave by Lexy Timms

Joy in the Morning by P. G. Wodehouse

End Me a Tenor by Joelle Charbonneau

The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters

The Refuge by Kenneth Mackenzie

A Leaf on the Wind of All Hallows: An Outlander Novella by Diana Gabaldon

Hour of Need (Scarlet Falls) by Leigh, Melinda

From The Wreckage - Complete by Michele G Miller

Untitled by Unknown Author

My Lord Rogue by Katherine Bone