Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (35 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

13.15Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Toward the end of

At the Earth’s Core,

after his second escape from the Mahars, while wandering through uncharted territory, Innes comes on a lovely valley that he describes as a “little paradise.” The chapter is titled “The Garden of Eden.” But Eden wouldn’t be complete without an Eve—or a serpent of sorts. Innes comes across a girl standing terrified on a ledge—his long-lost Dian the Beautiful—who’s being attacked by “a giant dragon forty feet in length,” with “gaping jaws” and “claws equipped with terrible talons.” Never a dull moment on Pellucidar. Innes saves her, realizing, finally, that he loves her. Their brief idyll is interrupted by Jubal the Ugly One, who’s been sniffing after Dian from the beginning. In their bloody duel to the death, crafty Innes prevails and has an inspiration in the moment of triumph: “If skill and science could render a comparative pygmy the master of this mighty brute, what could not the brute’s fellows accomplish with the same skill and science. Why all Pellucidar would be at their feet—and I would be their king and Dian their queen.”

At the Earth’s Core,

after his second escape from the Mahars, while wandering through uncharted territory, Innes comes on a lovely valley that he describes as a “little paradise.” The chapter is titled “The Garden of Eden.” But Eden wouldn’t be complete without an Eve—or a serpent of sorts. Innes comes across a girl standing terrified on a ledge—his long-lost Dian the Beautiful—who’s being attacked by “a giant dragon forty feet in length,” with “gaping jaws” and “claws equipped with terrible talons.” Never a dull moment on Pellucidar. Innes saves her, realizing, finally, that he loves her. Their brief idyll is interrupted by Jubal the Ugly One, who’s been sniffing after Dian from the beginning. In their bloody duel to the death, crafty Innes prevails and has an inspiration in the moment of triumph: “If skill and science could render a comparative pygmy the master of this mighty brute, what could not the brute’s fellows accomplish with the same skill and science. Why all Pellucidar would be at their feet—and I would be their king and Dian their queen.”

The sociopolitics of Pellucidar from here on are an eccentric amalgam of Arthurian legend, liberal Progressivism, and Teddy Roosevelt–style speak-softly-and-carry-a-big-stick democratic imperialism—an ideological stew representing Burroughs’s own jumbled worldview.

Innes and Dian make their way back to Sari, her homeland, and in nothing flat everyone agrees to his plan. An intertribal council is called and “the eventual form of government was tentatively agreed upon. Roughly, the various kingdoms were to remain virtually independent, but there was to be one great overlord, or emperor. It was decided that I should be the first of the dynasty of the emperors of Pellucidar.”

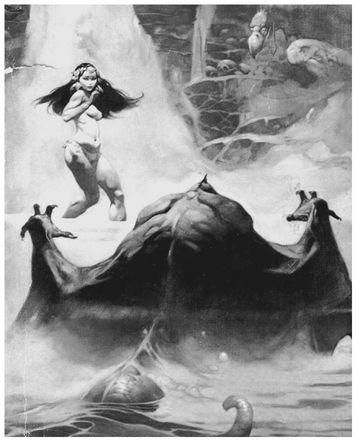

Dian the Beautiful as shown being menaced by Mahars on this 1970s Ace Paperback cover by Frank Frazetta. (© Frank Frazetta)

His goal? Freedom for enslaved humanity, achieved by the extermination of the Mahars. “How long it would take for the race to become extinct was impossible even to guess; but that this must eventually happen seemed inevitable.”

And how would this ethically dubious end be achieved? Superior weaponry. Perry has been experimenting with “various destructive engines of war—gunpowder, rifles, cannon and the like” but hasn’t been as successful as he hoped. Still, “we were both assured that the solution of these problems would advance the cause of civilization within Pellucidar thousands of years at a single stroke.”

In bringing civilization to Pellucidar, they plan to start with guns and genocide.

Innes will make a return trip to the surface in the iron mole to bring back weapons—along with books on such useful subjects as mining, construction, engineering, and agriculture. An arsenal of information to bring Pellucidar into the twentieth century, for better or worse. Works of literature do not appear on the wish list.

“What we lack is knowledge,” Perry exclaims. “Let us go back and get that knowledge in the shape of books—then this world will indeed be at our feet.” Yet another revealing slip. For all their supposed humanitarianism, Perry and Innes talk like megalomaniacs.

Innes plans to take Dian to the surface with him and show her the sights, but Hooja the Sly One, living up to his cognomen, pulls a switch, and Innes finds himself boring headlong upward with a creepy Mahar as a companion, not Dian the Beautiful. The iron mole comes out in the Sahara, and the novel ends with Innes and the bewildered Mahar waiting for someone to find them.

Nearly two years passed before Burroughs began work on

Pellucidar,

the second book in the series. Innes returns to Pellucidar in the iron mole with its cargo of guns and knowledge, but the steering

still

isn’t working right, so when he gets there, he’s lost. More captures, escapes, battles with terrible creatures. Hooja is on a rampage; he has raised a rebel force and has again kidnapped Dian. Innes is paddling away from Hooja’s ships in a small dugout. All seems hopeless, as usual, when the empire’s new fleet, fifty ships strong, sails onto the scene and defeats Hooja’s inferior forces. Ecstatic, Innes cries, “It was MY navy! Perry had perfected gunpowder and built cannon! It was marvelous!” They cream Hooja’s inferior forces. Plans for the empire shift into high gear and progress, of a sort, strikes poor Pellucidar.

Pellucidar,

the second book in the series. Innes returns to Pellucidar in the iron mole with its cargo of guns and knowledge, but the steering

still

isn’t working right, so when he gets there, he’s lost. More captures, escapes, battles with terrible creatures. Hooja is on a rampage; he has raised a rebel force and has again kidnapped Dian. Innes is paddling away from Hooja’s ships in a small dugout. All seems hopeless, as usual, when the empire’s new fleet, fifty ships strong, sails onto the scene and defeats Hooja’s inferior forces. Ecstatic, Innes cries, “It was MY navy! Perry had perfected gunpowder and built cannon! It was marvelous!” They cream Hooja’s inferior forces. Plans for the empire shift into high gear and progress, of a sort, strikes poor Pellucidar.

Like every boy of his time, Burroughs grew up on the medieval romances of Sir Walter Scott, but unlike most, he apparently hadn’t outgrown them by 1915—at the age of forty. Part of his charm, I guess. It seems safe to consider Innes an alter ego for Burroughs, and he indulges in some knights-in-shining-armor dreamin’ here. After the battle, Emperor David’s “fierce warriors nearly came to blows in their efforts to be among the first to kneel before me and kiss my hand. When Ja kneeled at my feet, first to do me homage, I drew from its scabbard at his side the sword of hammered iron that Perry had taught him to fashion. Striking him lightly on the shoulder I created him king of Anoroc. Each captain of the forty-nine other feluccas I made a duke. I left it to Perry to enlighten them as to the value of the honors I had bestowed upon them.”

Perry updates Innes on the improvements he’s made at Sari. Everyone has joined the cause against the Mahars, but beyond that Perry says, “they are simply ravenous for greater knowledge and for better ways to do things.” They mastered many skills quickly, and “we now have a hundred expert gun-makers. On a little isolated isle we have a great powder-factory. Near the iron-mine, which is on the mainland, is a smelter, and on the eastern shore of Anoroc, a well equipped shipyard.”

So the Pellucidarians, in a single bound, have leaped into the Industrial Age, and have been introduced to the joys of mines scarring the landscape, factories billowing smoke, and long, tedious work days.

Innes responds, “It is stupendous, Perry! But still more stupendous is the power that you and I wield in this great world. These people look upon us as little less than supermen. We must give them the best that we have. [You can practically hear the patriotic music begin to swell and see the flag proudly flapping in the breeze.] What we have given them so far has been the worst. We have given them war and the munitions of war. But I look forward to the day [music really swelling now, possibly a visionary tear in his eye] when you and I can build sewing machines instead of battleships, harvesters of crops instead of harvesters of men, plow-shares and telephones, schools and colleges, printing-presses and paper! When our merchant marine shall ply the great Pellucidarian seas, and cargoes of silks and typewriters and books shall forge their ways where only hideous saurians have held sway since time began!”

But before this grand vision can be realized, first they have to deal with those “haughty reptiles”—the evil Mahars. A council of kings convenes and decides to commence “the great war” against them immediately.

As Burroughs was writing this in January 1915, the real Great War was spreading like a terrible brushfire on the surface. In 1912–1913 small wars in the Balkans had begun bursting into flames out of seeming spontaneous combustion. Then on June 28, 1914, Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo. By summer’s end, declarations of war flying like dark, dry leaves, country after country found itself involved, and within months the fighting was burning its way through Europe with a ferocity unprecedented in history.

One might expect to see at least a glimmer of these events in “the great war” against the Mahars; and there is, though not much more, beyond the fact that Burroughs decided to make it part of the story in the first place. The main parallel is that Emperor David quickly gains many allies—nearly all the known tribes of Pellucidar are united for the first time against one enemy. The plan? “It was our intention to march from one Mahar city to another until we had subdued every Mahar nation that menaced the safety of any kingdom of the empire”—starting with Phutra, the Mahar capital.

The Battle of Phutra is a pretty good one. Burroughs didn’t entirely waste those years in military school and the army. A phalanx of Sagoths and Mahars engages the Empire’s forces outside the city but is “absolutely exterminated; not one remained even as a prisoner.” On to the city and its “subterranean avenues,” where the allies are temporarily stymied—the morally corrupt Mahars are using poison gas. But Perry jury-rigs a few cannon bombs, dumps them down the holes like oversize grenades, and

blam!

Mahars by the hundreds come streaming out of their underground lair like dazed wasps and, taking wing, flee to the north. After the fall of Phutra, victory follows victory—the Mahars are less tenacious than the Germans. Emperor David’s armies march “from one great buried city to another. At each we were victorious, killing or capturing the Sagoths and driving the Mahars further away.” The menace isn’t eliminated—“their great cities must abound by the hundreds and thousands [in] far-distant lands”—but they’ve at least been forced far from the Empire.

blam!

Mahars by the hundreds come streaming out of their underground lair like dazed wasps and, taking wing, flee to the north. After the fall of Phutra, victory follows victory—the Mahars are less tenacious than the Germans. Emperor David’s armies march “from one great buried city to another. At each we were victorious, killing or capturing the Sagoths and driving the Mahars further away.” The menace isn’t eliminated—“their great cities must abound by the hundreds and thousands [in] far-distant lands”—but they’ve at least been forced far from the Empire.

At the end of

Pellucidar,

David and Dian settle in to enjoy royal life in their “great palace overlooking the gulf.” Perry is working like a beaver on further “improvements,” laying out a railway line to some rich coalfields he wants to exploit. Sea trade between kingdoms proceeds apace, the profits going “to the betterment of the people—to building factories for the manufacture of agricultural implements, and machinery for the various trades we are gradually teaching the people.”

Pellucidar,

David and Dian settle in to enjoy royal life in their “great palace overlooking the gulf.” Perry is working like a beaver on further “improvements,” laying out a railway line to some rich coalfields he wants to exploit. Sea trade between kingdoms proceeds apace, the profits going “to the betterment of the people—to building factories for the manufacture of agricultural implements, and machinery for the various trades we are gradually teaching the people.”

Today we have nearly a hundred years of hindsight to wonder about the ultimate value of what Burroughs clearly sees as progress for Pellucidar. As Emperor David sums it up at the novel’s close, “I think that it will not be long before Pellucidar will become as nearly a Utopia as one may expect to find this side of heaven.”

Burroughs took fourteen years off from writing about Pellucidar, but in 1928–1929, in a burst, he produced

Tanar of Pellucidar

and

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

Both represented a falling-off from the earlier books. Whatever improbable coherence this inner territory had in the first two begins flying apart in these. Pellucidar increasingly seems less an intact world than an imperfect collection of shards, broken pieces lacking cohesion. Part of this is due to overcomplication. Savage countries, races, and creatures multiply like prehistoric rabbits in Burroughs’s attempts to ever increase the excitement by concocting yet another new kind. As Brian W. Aldiss observes in

Billion Year Spree,

“Burroughs never knew when enough was enough.” Just among the races, by series end there are Stone Age men, Sagoths (gorilla men), Mahars (brainy evil reptiles), Horibs (lizard or snake men), Ganaks (bison men, humanoid bovines), Gorbuses (humanoid cannibalistic albinos), Coripies (or Buried People; blind underground dwellers with no facial features, large fangs, webbed talons), Beast Men (savage vegetarians with faces somewhere between a sheep and a gorilla), Ape Men (black hairless skins, long tails, tree dwelling), Sabretooth Men, Mezops (copper-colored island dwellers), Korsars (descendants of pirates who accidentally sailed into the polar opening), Yellow Men of the Bronze Age—and I may be leaving some out. The overcomplication diminishes their impact. It is impossible to keep all these creatures and their various domains straight, and it’s arguable whether or not Burroughs managed to do so himself. With all these races always at odds with each other, there’s a growing feeling of fragmentation. Here in the center of the earth there’s no center, as one or the other of these squabbling races takes the stage to provide trouble for our various heroes, and everything else all but disappears from view. In both

Tanar

and

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

for instance, the evil Mahars, the chief scourge of Pellucidar in the first two novels, are hardly mentioned, even though they were only driven off, not exterminated as Perry had hoped. And the Empire that Perry and Innes have forcibly cobbled together also remains far offstage in these later two novels. Most of

Tanar,

essentially a rock ’em sock ’em adventure-filled love story between the title character and imperious Stellara, takes place among the Korsars, and in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

everybody spends most of their time lost in the jungle, fighting off one or another prehistoric monster—which Burroughs multiplies right along with the savage races. Especially in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core

there’s a sameness to the attacks, captures, escapes, followed by more attacks, captures, and escapes—as if Burroughs were operating more on autopilot than not.

Tanar of Pellucidar

and

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

Both represented a falling-off from the earlier books. Whatever improbable coherence this inner territory had in the first two begins flying apart in these. Pellucidar increasingly seems less an intact world than an imperfect collection of shards, broken pieces lacking cohesion. Part of this is due to overcomplication. Savage countries, races, and creatures multiply like prehistoric rabbits in Burroughs’s attempts to ever increase the excitement by concocting yet another new kind. As Brian W. Aldiss observes in

Billion Year Spree,

“Burroughs never knew when enough was enough.” Just among the races, by series end there are Stone Age men, Sagoths (gorilla men), Mahars (brainy evil reptiles), Horibs (lizard or snake men), Ganaks (bison men, humanoid bovines), Gorbuses (humanoid cannibalistic albinos), Coripies (or Buried People; blind underground dwellers with no facial features, large fangs, webbed talons), Beast Men (savage vegetarians with faces somewhere between a sheep and a gorilla), Ape Men (black hairless skins, long tails, tree dwelling), Sabretooth Men, Mezops (copper-colored island dwellers), Korsars (descendants of pirates who accidentally sailed into the polar opening), Yellow Men of the Bronze Age—and I may be leaving some out. The overcomplication diminishes their impact. It is impossible to keep all these creatures and their various domains straight, and it’s arguable whether or not Burroughs managed to do so himself. With all these races always at odds with each other, there’s a growing feeling of fragmentation. Here in the center of the earth there’s no center, as one or the other of these squabbling races takes the stage to provide trouble for our various heroes, and everything else all but disappears from view. In both

Tanar

and

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

for instance, the evil Mahars, the chief scourge of Pellucidar in the first two novels, are hardly mentioned, even though they were only driven off, not exterminated as Perry had hoped. And the Empire that Perry and Innes have forcibly cobbled together also remains far offstage in these later two novels. Most of

Tanar,

essentially a rock ’em sock ’em adventure-filled love story between the title character and imperious Stellara, takes place among the Korsars, and in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core,

everybody spends most of their time lost in the jungle, fighting off one or another prehistoric monster—which Burroughs multiplies right along with the savage races. Especially in

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core

there’s a sameness to the attacks, captures, escapes, followed by more attacks, captures, and escapes—as if Burroughs were operating more on autopilot than not.

Cover art for

Tanar of Pellucidar,

the third Pellucidar novel. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

Tanar of Pellucidar,

the third Pellucidar novel. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

Other books

Rules of Prey by John Sandford

Monster Hunter Memoirs: Grunge - eARC by Larry Correia

The Strange Attractor by Cory, Desmond

The Regal Rules for Girls by Fine, Jerramy

Pinball by Alan Seeger

A Taste of Seduction (An Unlikely Husband) by Campisi, Mary

A Dangerous Deceit by Marjorie Eccles

You Must Go and Win: Essays by Alina Simone

The Indigo Notebook by Laura Resau

B006NZAQXW EBOK by Desai, Kiran