Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (5 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

3.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And three from book two of Claudian’s

The Rape of Proserpine:

The Rape of Proserpine:

Amissum ne crede diem, sunt altera nobis

Sidera, sunt orbes alii, lumenque videbis

Purius, Elysiumque magis Mirabere Solem.

(As translated by Jacob George Strutt in 1814)… Think not to thee the light of day

For ever lost: we own a glorious sun;

And other stars adorn our firmament,

With purest splendor. How wilt thou admire

The beaming radiance of Elysian skies;

Halley comments, wryly: “And though this be not to be esteemed as an Argument, yet I may take the liberty I see others do, to quote the Poets when it makes for my purpose.”

One way or another, there is light down there sufficient to support life.

Somewhere along the way in this argument—after many readings I still find it difficult to pinpoint—truly warming to his subject, he raises the number of these interior spheres from one to three. He now refers the reader to a diagram appended to the end of the paper. Describing it, he says, “The Earth is represented by the outward Circle, and the three inward Circles are made nearly proportionable to the Magnitudes of the Planets

Venus, Mars

and

Mercury,

all of which may be included within this Globe of Earth, and all the Arches sufficiently strong to bear their weight.”

Venus, Mars

and

Mercury,

all of which may be included within this Globe of Earth, and all the Arches sufficiently strong to bear their weight.”

There it is. Three independently moving spheres inside, well-lit and capable of supporting life. The paper concludes on a brave note, though tinged with a defensive twitch or two:

Thus I have shewed a possibility of a much more ample Creation, than has hitherto been imagined; and if this Seem strange to those that are unacquainted with the Magnetical System, it is hoped that all such will endeavor first to inform themselves of the Matter of Fact and then try if they can find out a more simple Hypothesis, at least a less absurd, even in their own Opinions. And whereas I have adventured to make these Subterraneous Orbs capable of being inhabited, ’twas done designedly for the sake of those who will be apt to ask

cui bono

[What is the good of it?], and with whom Arguments drawn from

Final Causes

prevail much. If this short Essay shall find a kind acceptance, I shall be encouraged to enquire farther, and to polish this rough Draft of a Notion till hitherto not so much as started in the World, and of which we could have no Intimation from any other of the

Phenomena

of Nature.

It should be noted that except for the life and light he posited down there, for which science fiction writers have been thanking him ever since, but about which, per the above, he obviously had certain reservations—his ideas regarding the causes of the earth’s magnetism and the complicated shifts in the magnetic poles were quite prescient and not far in principle from current thinking. According to recent Halley biographer Alan Cook, “he showed an understanding of the essential structure of the Earth’s magnetisation.” The earth does consist of separate spheres of a sort: the outer crust; the mantle, which accounts for two-thirds of the planet’s mass; a dense liquid layer of magma consisting chiefly of molten iron that’s about half the earth’s radius in extent; and a solid inner core inside that. The layer of molten metal is circulating—like Halley’s internal Sphere—which creates electrical currents, which in turn create magnetic fields. The earth can be thought of as a great electromagnet. Even today all of this isn’t entirely understood. But Halley was closer to being on the right track than it might seem at first blush.

In 1716, England was treated to a spectacular aurora borealis display—another phenomenon little understood at the time, and not completely so now. This came at the end of the “maunder minimum” in Europe and England, a period of low sunspot activity lasting from 1645 to 1715 that coincided with a near absence of the northern lights. Halley observed the display and wrote a paper offering an explanation for it that involved his theory of the hollow earth. He rightly supposed that the earth’s magnetic field played a part in creating the aurora. Alan Cook comments that “his analysis of the structure of aurorae and their correspondence with the Earth’s magnetic field remains impressive after nearly three hundred years.” Halley further speculated—incorrectly—that the source of the particles reacting to the magnetic field to create the aurora might be the “medium” between the shell and the first internal sphere leaking out into the atmosphere. It might tend to leak more at the poles because, as Cook puts it, he believed that there “the shell is thinnest on account of the polar flattening of the earth.”

At the age of eighty, Halley sat for what would be his last portrait. It is far different from the earliest known portrait of him at about age thirty, with long black hair dropping to his shoulders, in which he looks rather remarkably like a young Peter Sellers, with an expression on his face combining determination with a gleam of mischief in the eyes. In this later portrait his long wavy hair has gone white, he’s added a few pounds, and his face shows patient resolve, like he’d rather be anywhere else than sitting still for this portrait painter. He’s wearing a black velvet scholarly robe with lacy white shirt cuffs poofing out of the sleeves, and he seems to be standing in his library, with a number of large volumes on shelves behind him. It would be unremarkable but for the large sheet of paper he holds in his left hand, angled so the viewer can see what’s on it—a drawing of spheres within spheres, almost identical to the one appended to his 1692 paper on the hollow earth in the Royal Society’s

Philosophical Transactions.

Of the hundreds of projects he’d involved himself in, with accolades given for his work in dozens of areas, he remained fond and proud enough of his hollow earth theory to have it memorialized in what he must have suspected would be the last official portrait done of him. Those natural philosophers, the Beach Boys, would approve: Be true to your school!

Philosophical Transactions.

Of the hundreds of projects he’d involved himself in, with accolades given for his work in dozens of areas, he remained fond and proud enough of his hollow earth theory to have it memorialized in what he must have suspected would be the last official portrait done of him. Those natural philosophers, the Beach Boys, would approve: Be true to your school!

Halley would probably have been flattered, amused, and appalled at the uses to which his theory would be put in the years to come.

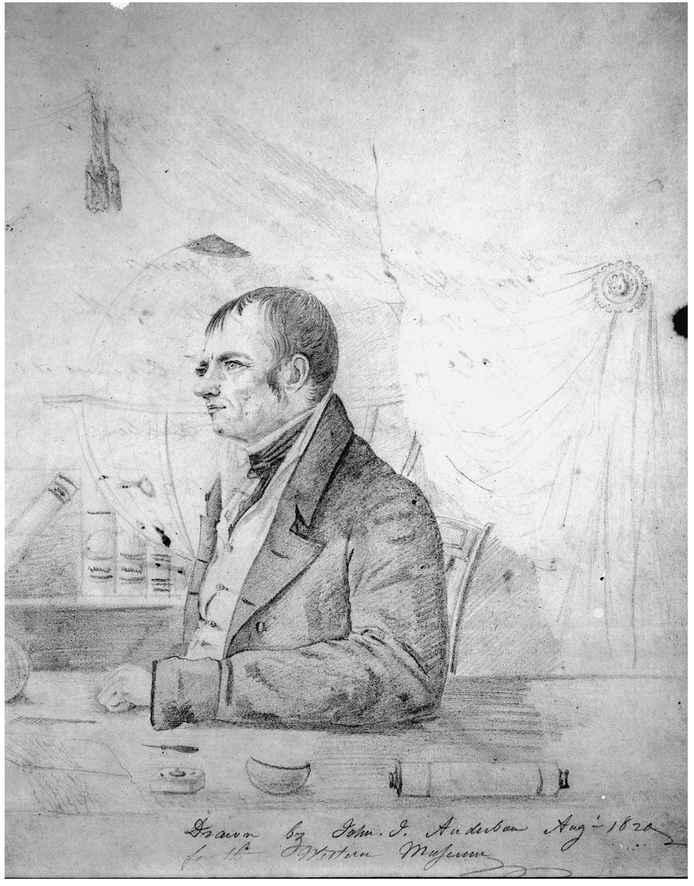

John Cleves Symmes portrait by John Audubon. (Collection of the New York Historical Society)

2

SYMMES’ HOLES

THE NEXT MAJOR HOLLOW EARTH EVENT BEGAN MODESTLY

on April 10, 1818, in St. Louis, then the westernmost town of any size on the American frontier. Founded in 1764, the former French trading post had grown from a muddy backwater into a booming crossroads, becoming the stepping-off point to the West. The Lewis and Clark expedition embarked from there in 1804, the year after the Louisiana Purchase, an 827,987-square-mile tract of land that doubled the size of the country, bought from Napoleon at the bargain-basement price of a little under three cents an acre. In 1805 St. Louis was made the Territory of Louisiana’s seat of government, and then in 1812, capital of the Territory of Missouri. Between 1810 and 1820 the population increased 300 percent. When the War of 1812 concluded in December 1814 (not counting the belated Battle of New Orleans), people began pouring in there, whether seeking boomtown opportunity or simply stopping to take a few deep breaths and buy some (overpriced) pots and pans before heading farther west. One of the new steamboats first put in there in 1817, beginning a traffic that would give St. Louis a prominence in the West that would last until the coming of the railroad in the 1840s and 1850s, when previously piddling Chicago would eventually steal its thunder. In the years immediately after the War of 1812, St. Louis was ripping and roaring.

on April 10, 1818, in St. Louis, then the westernmost town of any size on the American frontier. Founded in 1764, the former French trading post had grown from a muddy backwater into a booming crossroads, becoming the stepping-off point to the West. The Lewis and Clark expedition embarked from there in 1804, the year after the Louisiana Purchase, an 827,987-square-mile tract of land that doubled the size of the country, bought from Napoleon at the bargain-basement price of a little under three cents an acre. In 1805 St. Louis was made the Territory of Louisiana’s seat of government, and then in 1812, capital of the Territory of Missouri. Between 1810 and 1820 the population increased 300 percent. When the War of 1812 concluded in December 1814 (not counting the belated Battle of New Orleans), people began pouring in there, whether seeking boomtown opportunity or simply stopping to take a few deep breaths and buy some (overpriced) pots and pans before heading farther west. One of the new steamboats first put in there in 1817, beginning a traffic that would give St. Louis a prominence in the West that would last until the coming of the railroad in the 1840s and 1850s, when previously piddling Chicago would eventually steal its thunder. In the years immediately after the War of 1812, St. Louis was ripping and roaring.

One of those who landed there after the war was Captain John Cleves Symmes.

On April 10, 1818, he commenced handing out a printed circular of his own composition. It was his bold mission statement:

CIRCULARLight gives light to discover—ad infinitumST. LOUIS, MISSOURI TERRITORY, NORTH AMERICAApril 10, a.d. 1818To all the World:I declare the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles twelve or sixteen degrees. I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in this undertaking.JNO. CLEVES SYMMESOf Ohio, late Captain of InfantryN.B.—I have ready for the press a treatise on the principles of matter, wherein I show proofs of the above positions, account for various phenomena, and disclose Dr. Darwin’s “Golden Secret.”My terms are the patronage of THIS and the NEW WORLDS.I dedicate to my wife and her ten children.I select Dr. S.L. Mitchill, Sir H. Davy, and Baron Alexander Von Humboldt as my protectors.I ask one hundred brave companions, well equipped, to start from Siberia, in the fall season, with reindeer and sleighs, on the ice of the frozen sea; I engage we find a warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals, if not men, on reaching one degree northward of lattitude 82; we will return in the succeeding spring.

4J.C.S.

This wasn’t a stray brainstorm that occurred to him during a nightmare brought on by a bad fish or after getting a little too corned up at the tavern. He had been thinking and thinking on this. How he came to these conclusions—and how he came to believe so passionately and persistently in them—is a mystery. But until he died in 1829 at age forty-eight, the hollow earth was his obsession, his only dream, his tragedy.

Born in Sussex County, New Jersey, in 1780, Symmes was named for a prominent uncle whose generosity would figure in his future. The older Symmes was a Revolutionary War veteran and chief justice of New Jersey, who in 1787 put together a corporation to buy a 330,000-acre tract of public land in the southwestern corner of the present state of Ohio, between the Big and Little Miami rivers, north of the Ohio River, a deal sometimes known as the Symmes Purchase.

His younger namesake started out well enough. His father, Timothy Symmes, was a Revolutionary War veteran and a judge in New Jersey who married twice and had nine children altogether. John Cleves was the oldest in the second crop of six. He had the usual semi-haphazard elementary education. Years later he recalled reading, at age eleven, “a large edition of ‘Cook’s Voyages,’” which his father, “though himself a lover of learning, reproved me for spending so much of my time from work, and said I was a book-worm.”

5

He added that at “about the same age I used to harangue my playmates in the street, and describe how the earth turned round; but then as now, however correct my positions, I got few or no advocates.” Poor Symmes. Already a visionary pariah in grade school.

5

He added that at “about the same age I used to harangue my playmates in the street, and describe how the earth turned round; but then as now, however correct my positions, I got few or no advocates.” Poor Symmes. Already a visionary pariah in grade school.

He joined the army as an ensign—the lowest officer rank—at age twenty-two and was commissioned as captain in January 1812, months before war was declared against Great Britain. He did most of his service on the western frontier near the Mississippi River.

Symmes was at Fort Adams fifty miles below Natchez in 1807, as the final act in Aaron Burr’s delusional scheme of personal empire was unfolding near there. Another dreamer! Burr was on his way down the Mississippi with an armed flotilla, rumored to be planning to seize New Orleans, in cahoots with the territorial governor, James Wilkenson. But Wilkenson got cold feet, ratted Burr out to President Jefferson, and rushed additional troops to several forts along the river, including Fort Adams, ordering those stationed in New Orleans to prepare for an attack. Burr got wind of this betrayal and went ashore north of Natchez, where he was arrested. Managing to fast-talk his way out of the charges, he masqueraded as a river boatman and melted into the wilderness on the eastern side of the river, making his way toward Spanish Pensacola. But as additional information about his schemes came to light, he was rearrested near Mobile and taken to Richmond, where he was tried for treason before Chief Justice John Marshall—and, somehow, acquitted.

Other books

The Avenger 7 - Stockholders in Death by Kenneth Robeson

Aunt Dimity and the Next of Kin by Nancy Atherton

Weapon of Vengeance (Weapon of Flesh Trilogy) by Jackson, Chris A.

Eleanor by Joseph P. Lash

Fast Forward by Celeste O. Norfleet

Vegan Diner by Julie Hasson

Blood Dance by Lansdale, Joe R.

Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming's Jamaica by Matthew Parker

Best Enemies (Canterwood Crest) by Burkhart, Jessica

Love on the Rocks (Bar Tenders) by Melanie Tushmore