Horns & Wrinkles

Authors: Joseph Helgerson

Joseph Helgerson

illustrations by Nicoletta Ceccoli

houghton mifflin company boston

Thanks to my fellow sandbar campers: Maggie, Jake, Helen Kay,

Darlene, Pip, Bill, Rich, Pooch, and Lady. And thanks to

Kate O'Sullivan for help along the way.

Text copyright © 2006 by Joseph Helgerson

Illustrations copyright © 2006 by Nicoletta Ceccoli

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The text of this book is set in 11-point Dante.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Helgerson, Joseph.

Horns and wrinkles / by Joseph Helgerson ; illustrations by Nicoletta Ceccoli.

p. cm.

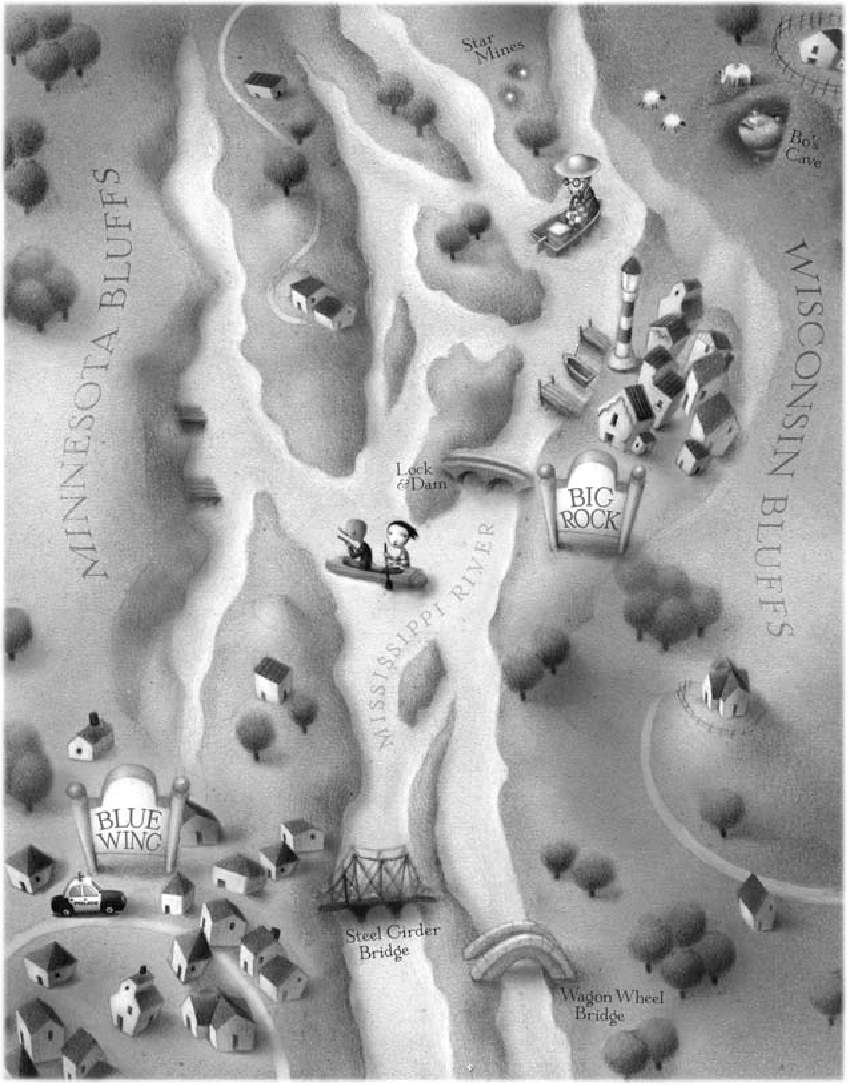

Summary: Along a magic-saturated stretch of the Mississippi River near Blue Wing, Minnesota,

twelve-year-old Claire and her bullying cousin Duke are drawn into an adventure involving Bodacious

Deepthink the Great Rock Troll, a helpful fairy and a group of trolls searching for their fathers.

HC ISBN

-13: 978-0-618-61679-4

PA ISBN

-13: 978-0-618-98178-6

[1. MagicâFiction. 2. TrollsâFiction. 3. BulliesâFiction. 4. Mississippi RiverâFiction.]

I. Ceccoli, Nicoletta, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.H37408Hor 2006 [Fic]âdc22 2005025448

Book design by Maryellen Hanley

Printed in the United States of America

QUM

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for

MAGGIE

JAKE

&

HELEN KAY

CLAIRE'S FAMILY

FRAN, LILLIE, & TESSAÂ sisters

ADAM & LINDA parents

DUKE cousin

PHYLLIS & NORM aunt & uncle (Duke's parents)

GRANDPA B grandfather

HUNTINGTON & NETTIEÂ great-great-great-grandparents

FLOYD great-great-great-granduncle (Huntington's brother)

TROLL CLANS

EEL-TONGUE Jim Dandy

Double-knot (Jim Dandy's father)

Two-cents (Jim Dandy's mother)

MOSSBOTTOM Biz "Squeak"

FISHFLY Stump

Duckwad

SLICE-TOE Tar-and-feathers (Biz's great-aunt)

CROWLEG Muck(Biz's wife)

Weed (Biz's wife)

Scale(Biz's wife)

DEEPTHINK Bodacious

LEECHLICKER Fancy (Jim Dandy's wife)

GARTOOTHÂ Wishy (Stump's wife)

Falling

My cousin Duke's troubles on the river started the day he dangled me off the wagon wheel bridge. It's an old stone bridge, abandoned now, except for bullies and the occasional river troll in need of a hideout.

"Take it back?" Duke shouted, holding me by the ankles.

He was shaking me so hard that my lucky penny slipped out of my pocket and plopped into the river. You can take that as a sign if you want to, but it was Duke's luck, not mine, that went bad.

"Not in a million years," I told him.

The river I was hanging over was the Mississippi, which was flooding, all muddy and solid-looking as a freight train, about twenty feet below my ponytail. It was early May. None of the trees had turned green yet, but you could smell it coming fast.

I'd been out in my front yard that Saturday morning, exercising my friend Lottie, a box turtle who had wintered in my closet. Enter Duke, who'd scooped Lottie up, claiming she'd make some troll a nice snack.

Since I wasn't big enough to stop him, I pleaded with him all the way to the river, where he tossed her in. For good measure, he tried to push me in too. That was a mistake. He forgot how hard I can hold on to thingsâlike his wrist. We landed side by side, flat on our faces in water that had been frozen ice but a short while back. Our yowls scared birds off trees.

By the time I'd struggled back to shore, floodwaters had carried Lottie away.

If I were braver, I'd have jumped in after her, but our stretch of river is a queer old chunk of water. Though nobody likes to talk about it much, the river around here is under a spell of some kind. Crippled people have been known to drive cross-country and plop down in it for a cure. And besides, I couldn't very well go after Lottie while Duke was dragging me up the bridge.

As soon as he dangled me over the edge, I saw a crutch go bobbing by beneath me, headed for New Orleans, along with all sorts of other incredible fare: a crow perched atop a dollhouse, a muskrat holding an orange tennis shoe in its mouth, a log with a dozen turtles along its spine. Maybe Lottie would hook up with them. I hoped so. With the river suffering spring fever, everything was on the move.

"You better know how to swim," Duke shouted.

It was one of his shouting days. Most were. Looking skyward, I could see up his nostrils, which seemed huge and dark as caverns.

"You know I can't," I said.

"Time you learned."

"I'll be the judge of that," I informed him, knowing better than to sound the least bit fluttery, even though I was a goner if he let go. You don't want to sound afraid of a bully, especially if he's a relative.

Duke was tall for an eleven-year-oldâat least a head taller than I was even though I was a year olderâand sort of pillowy soft. (Don't ever mention the pillows to him, though.) He was a fiery redhead and wore his hair short as fur, which is what it felt like if you sneaked a rub. Better not. Freckles? Lots. They were off-limits too. He was proud of his temper like peacocks are of their tails. His snub nose twitched every few seconds in case anything was cooking nearby, for if there was, he planned on being there first. He wore a black jacket with lots of zipper pockets that were full of treats and stuff confiscated from small fry.

At the moment we were disagreeing about my baseball cap, which he'd snatched while dragging me up the bridge. He was wearing it but claiming he wasn't. I can't even think why he'd want to wear a cap with a girl's name on it, except to start an argument.

"Say your prayers, Claire!" Duke shouted.

But before he could think of how to threaten me next, a sweet old voice called up to us from below.

"Excuse me," the old voice said, "have you seen a muskrat go by?"

Floating below us was a tall old lady in a red rowboat with yellow seats. She wore a blue flowery dress, a red checkered apron, and one orange tennis shoe, a high-top. Her other foot was bare. Her hands and apron had a dusting of white flour, and I caught a whiff of homemade bread.

"Beat it, you old bat!" yelled Duke.

"His name is Prince Leopold," the old lady said, unperturbed, "and he was carrying one of my sneakers."

"Can't you see I'm busy?" Duke shouted.

"I think he went that way." I pointed where the muskrat had been headed.

"You stay out of this," Duke warned me.

"Is that a girl you're holding?" the old lady politely asked. She held her hands above her eyes to shield against sun glare off the water.

"It's a warthog," Duke shouted.

"It doesn't look like a warthog." The old lady tilted her head sideways for a better view. "I'd say it looks like a girl."

"Are you calling me a liar?"

The old lady thought that over. Reaching into an apron pocket, she pulled out a pinch of what looked like flour and blew it toward us. The flour glittered in the sun and dusted my face. I'm afraid I giggled.

"Sounds like a girl," the old lady judged.

That scorched Duke's cheeks and started a rumble shimmying up his throat. The last time I'd seen him this mad was when he'd salt-and-peppered a grasshopper but couldn't make me eat it. Leaning over the edge of the bridge to aim me better, he shouted, "You asked for it!"

His grip tightened around my ankles as he positioned me for a direct hit. The old woman shook her head sadly at his efforts and called out, "You're sort of a wimp, aren't you, son?"

Squinting one eye, Duke lined me up perfectly with the rowboat and broadcast with a great deal of satisfaction, "Bombs away!"

A half-minute later nothing had happened. Between Duke's sweaty palms and my dripping socks, I began to worry that I might slip out of his grasp before he could drop me.

"I'm waiting," the old lady called out.

For ever after, Duke always claimed he might never have let go if she hadn't driven him to it.

You might think it wouldn't take long to fall twenty feet, but believe me, it can take up most of a day. My eyes were open all the way too. The wind fluttered my ponytail and tickled my one crooked tooth. I tried righting myself so that I wouldn't hit headfirst, but I rolled too far and did a full somersault. Everything seemed stuck in turtle time.

Up on the bridge, Duke's eyes were large as tennis balls.

Down below, the old lady had positioned a plump cushion on the seat where I was headed. She sat with her hands folded on her lap, as if waiting for someone invited to tea. Beside the boat, a muskrat head popped out of the water, holding an orange tennis shoe in its mouth. One look at me falling out of the sky made him dive elsewhere.

Now that I was closer to the old lady, I could see that reading glasses hung around her neck on a gold chain. Wisps of white hair poofed out around a straw hat. Her face was friendly as a daisy's.

I had time to take all that in, and still I wasn't done falling. In the name of science, I decided to try an experiment and counted to ten, real slow.

After that there wasn't much doubt, but I counted to ten again, even slower, just to make sure. That made it official: something rivery was happening. At the moment, I was drifting downward with all the speed of dandelion fluff. Tucking my feet under me, I alighted on the boat cushion like a perfect lady.

"Hello," the old lady greeted. "I'm so glad you could join me."

She smiled as though we were old friends.

"Pleased to meet you," I said. "Did you do that?"

I was gesturing toward the bridge above us, the one I'd just been dropped from.

"Do what?" she asked.

A commotion from atop the bridge cut off my answer.

"My nose! My nose!"

Glancing up, I saw Duke dancing around, holding his face as if he'd just been punched on the snout. As far as I could tell, he was all alone on the bridge.