Horns & Wrinkles (21 page)

Authors: Joseph Helgerson

Down and down we went, falling slow as a balloon that's thinking about going up.

Right away I could smell trolls, all mildewy and sweaty and moldy. It got colder. Damper. But that was all kids' stuff compared to the view in front of me.

The spot where Farmer Bailey dropped his hay bales was the shallow part of the cavern. At the other end, lit up by shooting-star lanterns, the cavern opened into a space big enough to swallow several pods of whales. I could see trolls swinging pickaxes and hauling rock in wheelbarrows, and all the while they were pushing, shoving, and shouting. The cavern was riddled with holes, false starts to the moon, I supposed.

Right at the center of all the action stood Bodacious Deepthink, the Great Rock Troll herself, looking two or three times bigger underground. That was probably because she was standing up straighter and wearing a construction hat, along with her tiger-striped nylon outfit.

Crouching beside her was Jim Dandy's father, Double-knot Eel-tongue, with a blueprint spread over his back. Looking from the blueprint to her miners, Bo belted out an angry stream of orders.

"Faster!"

"Deeper!"

"No snacking!"

The Great Rock Troll kept spinning this way and that, and every time she shifted, she expected Double-knot to move with her. But being asked to scurry around on all fours wasn't the worst of Double-knot's problems, not by a long shot.

Every so often Bo needed a breather from all her shouting and braying. Whenever that happened, Double-knot was supposed to rush behind her and become a stool. As she sat down on him, he sagged and creaked and groaned, all of which tickled Bodacious Deepthink no end.

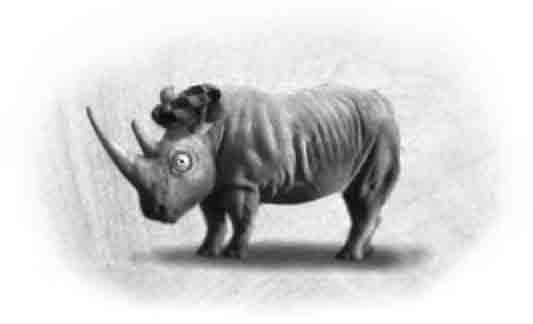

But the sight that stole my breath away was a large rock corral that was separated from the rest of the cave by an underground stream. The trolls were leading the hay cart across a short stone bridge to that corral. Milling around on the other side of that bridge were twenty to thirty bullies, a whole herd of them. They all looked as though wishing they'd never picked on anyone smaller than themselves in their whole life. How could I tell they were bullies? They were all rhinoceroses.

Coo-Coo-Ba-Roo

If you ever land in a cave full of rock trolls, remember not to breathe deep. The air trapped in that cave hasn't been around any roses.

The other reason you dare not breathe is that rock trolls might hear you. In a cave, everything echoes, and rock trolls have ears the size of lumpy baseball mitts. Luckily, the cave we were sinking into was so full of soundsâringing pickaxes, shouting rock trolls, snorting rhinos, chirping cave cricketsâthat the thumps we made upon landing were hardly noticed at all.

"You hear something?" grumbled a rock troll pushing a wheelbarrow.

"Moonbeams," scoffed his partner without even stopping.

The old lady waved us behind a stalagmite and whispered, "We'll wait here until dawn."

It wasn't a night I'll forget soon enough. There was no mistaking rock trolls for anything else I'd ever heard of, not even river trolls. If you have any boulders in your family, you'll know what I'm talking about. The trolls before us were bald and bumpy and had very little bend to them. Heavy as their feet were, they shuffled everywhere. The liveliest thing about them was their eyes, which sparkled like split diamonds in the lantern light.

The cavern floor shook with their digging. They yelled about everything, then had to shout louder to be heard above their own echoes. Smashing rocks made them laugh. Fighting with each other made them happy. Lighting fuses made them try to dance, which usually led to a fall. They hauled rock until they broke for supper, or whatever you call a meal taken in the middle of the night. When they ate, their slurping echoed like breakers on an ocean beach.

Back at work, they started burping. There were fumes.

At last, morning. Our end of the cave began to lighten to a mousy gray, thanks to the hole in Farmer Bailey's pasture. The trolls noticed the change almost at once and dropped everything but their grumbling. The bunch closest to us carried on like this:

"We'll never reach the moon at this rate."

"Somebody ought to go up there and smash that sun."

"You ignoramus. We don't have any ladders that high."

"Couldn't we build one?"

"When, on our day off?"

Which started a whole new round of bickering, for they never got a day offânot even holidays or birthdays. Slowly, they drifted off to holes and crevices for a long day's sleep. Two or three trolls stumbled around covering up lanterns with burlap bags that said

BIG ROCK FEED AND SEED.

The shooting stars winked out one by one until the only light in the cave was the pale glow from the hole in Farmer Bailey's pasture.

"We'll wait until they're sound asleep," the old lady whispered.

Before I could ask how long that would take, a voice filled the cavern with a lullaby that was soft and sweet as a chorus of nightingales. Peeking around my stalagmite, I saw Bodacious Deepthink singing with her arms outstretched, eyes closed, and bat earrings fluttering about her head.

The moon is down below us

Singing to us all.

coo-coo-ba-roo

coo-coo-ba-rooJust close your eyes and listen.

You're sure to hear its call.

coo-coo-ba-roo

coo-coo-ba-rooYou'll find yourself smiling.

You're going to take a fall.

coo-coo-ba-roo

coo-coo-ba-rooThe day we finally reach it

We're going to have a ball.

coo-coo-ba-roo

ba-roo ba-roo

who-coo

coo-coo-coo

coo-coo

By the time she'd crooned her way through the lullaby twice, the snores in the cave sounded like a thousand sloppy geysers. Double-knot Eel-tongue had collapsed in a heap at her feet.

Leaving Jim Dandy's father right where he lay, Bodacious Deepthink clumped to the stone bridge that arched over the underwater stream and led to the rhinos. Halfway across she flopped down sideways with a thud. You could hear her humming the lullaby to herself until she too fell asleep, blocking the only way to the rhinos. Her snores were louder and dreamier than all the other hissing and fizzing that filled the place.

"How do we get around her?" I whispered.

"Easy," the old lady said.

When we started walking, I saw what she meant. My feet still held some of the bubbles that had let me float down from Farmer Bailey's pasture. With a helping boost from the old lady, Stump and I leaped the stream in one bound. Once across, the old lady motioned for Stump to hang back in the shadows.

"You might spook 'em."

Then she and I stepped up to the corral's rock fence, which came up to my chin.

From up close, the rhinos that I could see weren't plump, and their wrinkly skins looked ready to slip off. Remnants of clothes clung to their pointy ears, bony legs, and knobby ankles. They wore socks without heels, flattened caps, and tattered pant legs and shirtsleeves, though never the whole pants or shirt. One rhino wore a black eye patch that looked left over from Halloween, and two girl rhinos had dabs of fingernail polish on their hoovesâlime green and ketchup red. Bodacious Deepthink's lullaby hadn't soothed the herd at all. They stood paired off, butting heads, going horn to horn, with much pushing, grunting, and name-calling, all done in hushed whispers so as not to wake the Great Rock Troll. What we heard was pretty standard stuff for bullies:

"I'm bigger."

"Than a peach pit."

"One step closer and I'll peach pit you."

"One step? I didn't know you could count that high."

"Try me and see."

Some rhinos were claiming to be geniuses or related to royalty or in possession of a secret map that showed the way out of the cave. In fact, several bragged up secret maps. The way they were all jostling and pushing and milling around made it impossible to pick Duke out of the crowd, so finally I gave up looking and called out in a hushed voice, "Duke."

Nobody paid attention.

"Duke," I called again.

Finally, the oldest-looking rhino in the herd hobbled over, snuffling all the way. His wrinkled gray skin hung on him like draperies. His horn was chipped, and the hair in his ears stuck out like thornbushes. Squashed atop his head was a shapeless hat that had aged worse than him, if that was possible.

Since rhinos have such poor eyesight, he had to stick his face, horn and all, over the stone fence to see us. After several deep sniffs and a lot of blinking, he shook his head from side to side, as if he still couldn't believe what what he was seeing, and said, "Is that you, Nettie?"

Floyd Titus Bridgewater

How could a rhinoceros trapped in a cave mistake me for my great-great-great-grandmother? The answer came from the old lady, who advised me, "Ask if he's Floyd."

I didn't need to ask, though. The rhino heard her and said, "Floyd Titus Bridgewater, at your service, ladies. At your service."

And he made a short bow that started several of the closer rhinos ragging on him:

"Would you look at old Floyd."

"Thinks he's a gentleman."

"The old fool."

The old lady nudged me forward. "Tell him who you are."

"My name is Claire Antoinette Bridgewater," I said, feeling shy enough to turn formal. "Nettie Bridgewater was my great-great-great-grandmother."

"Now, how can that be?" Floyd asked. "I've only been down here a few weeks. Months at the most."

"I think it's safe to say it's been longer than that," the old lady said.

"Who are you?" Uncle Floyd demanded, perturbed.

"Friend of the family," the old lady breezed on, "and Nettie's sent you a message."

"What kind of message?" Uncle Floyd turned cautious.

"Well," I started, after the old lady nudged me again, "she said to tell you to hurry up."

At that, the old rhino muttered considerably, saying to himself, "Sounds like Nettie, all right." Raising his head to us, he added, "She was a bossy little thing, worse than a princess. Well, if you're her great-great-great-granddaughter, I guess that means my fool brother went ahead and got hitched to her. Serves him right, I'd say." He carried on that way until he got around to saying gruffly, "I guess that makes me your uncle."

"Don't worry," I declared, standing up to him. "I won't tell anyone."

"Likewise," he grumped.

But I could tell I'd won him over just a bit by showing some backbone. Dealing with Duke had taught me a thing or two after all, at least when it came to bullies. Remembering how Grandpa B liked nothing better than being questioned about bygone days, I asked, "But how have you lasted down here so long?"

"Sentimental reasons," he confided. "I'm the first bully Bodacious Deepthink ever caught, so she likes to keep me around. But enough about me. What in the world are you two doing down here? It's not a proper place for ladies."

"I need to talk to my cousin Duke," I said.

"Which Duke is that?"

"How many have you got?" the old lady asked him.

"Three. Four if you count the lunkhead got dumped off last night."

"That's the lunk we want," the old lady said.

"He's over there eating himself silly." Uncle Floyd pointed with his horn. "You sure he's a Bridgewater?"

Off to one side, cloaked by shadows, stood a rhino munching away on Farmer Bailey's hay. The black zipper jacket hanging around his neck said it was Duke. He was fatter and shinier than the rest of the herd, and I didn't see any way we'd ever float him out of the hole in Farmer Bailey's field. Even the rhinos who were nothing but skin and bones didn't look like they could be squeezed out that way.

"Sure as can be," I muttered, wishing otherwise. "His mother's a Bridgewater."

"You here to spring him?"

"That's the plan," the old lady said.

"How?"

"Knock out the lights and run."

"Some plan," Uncle Floyd pooh-poohed.

"We'll listen to anything better."

"You know," Uncle Floyd admitted after some thought, "these trolls aren't exactly packed with brains. Maybe your idea would work. If you know the way out, that is."