House of Hits: The Story of Houston's Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios (Brad and Michele Moore Roots Music) (18 page)

Authors: Roger Wood Andy Bradley

Tags: #0292719191, #University of Texas Press

But before that D Records single was released, and just a few weeks after his initial session at Gold Star, Nelson returned to Quinn’s big room to record again, and this time he experienced a breakthrough epiphany. Using three of the members of the previous session band—Buskirk, Reynolds, and Hagy—plus Bob Whitford on piano, Herb Remington on steel guitar, and Dick Shannon on vibraphone and saxophone, Nelson performed two more of his own recent compositions, “Rainy Day Blues” and “Night Life.”

As Patoski indicates, the former song “showed Willie had chops as a guitarist.” But it was the musical results on the latter that triggered a career-changing moment for the artist. Patoski continues,

“Night Life” was from another realm. Mature, deep, and thoughtful, the slow, yearning blues had been put together in his head during long drives across Houston. At Gold Star, he was surrounded by musicians who could articulate his musical thoughts. He sang the words with confi dent phrasing that had never been heard on any previous recording he’d done. . . .

“It was a level above what we had been doing,” Willie said of the session.

d a i ly ’ s d o m i n a n c e a n d d r e c o r d s

7 9

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 79

1/26/10 1:12:14 PM

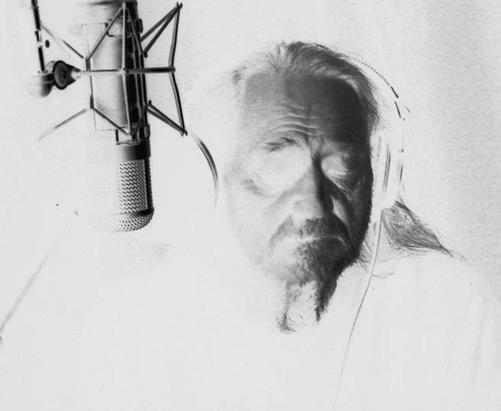

Willie Nelson, 2008 (photo by and

courtesy of Gina R. Miller)

Now if Daily’s discernment on such matters had been impeccable, that inspired performance by Nelson and the band might have yielded yet another D

Records hit. But Daily reportedly despised “Night Life,” dismissing it gruffl y

as not “country” enough and refusing to issue it.

As a result, the disgruntled Nelson and his studio bandleader Buskirk conspired to abscond with the tape, which they paid to have mastered at Bill Holford’s ACA Studios, and then on their own they released “Nite Life” (with the indicated change of spelling in the title) on the tiny Rx label under the name Paul Buskirk and His Little Men featuring Hugh Nelson. Only a small number of copies were ever pressed, and, backed by no strategy for promotion or distribution, that recording all but disappeared without notice. In fact, though Nelson would obviously record new versions of “Night Life” over subsequent years, that original treatment from his Gold Star sessions would not be released under his own name until 2002, when it was included among

The

Complete D Singles Collection

CD boxed sets issued by Bear Family Records in Germany.

Though he would later become famous for recordings made elsewhere (and would record for a SugarHill Studios project in 2008), Willie Nelson may well have fi rst realized his aptitude for greatness during those 1960 sessions for D Records at Gold Star Studios.

8 0

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 80

1/26/10 1:12:14 PM

through the early 1960s d records continued to use Quinn’s Gold Star Studios to document a wide range of Houston-based artists. Representative examples include Johnny Nelms, who waxed “Old Broken Heart” and “I’ve Never Had the Blues” in February 1961 (#1178); Perk Williams, who cut

“What More” and “Are You Trying to Tell Me Goodbye” that same month (#1182); Herb Remington, who made “Fiddleshoe” and “Soft Shoe Slide” in March 1961 (#1186); Link Davis, who recorded “Come Dance with Me” and

“Five Miles from Town” that same month (#1191); and Al Dean doing “I Need No Chains” and “A Girl at the Bar” in May 1961 (#1192).

While the prolifi c D Records was continuing to produce new singles, in May of 1961 Daily also convinced Mercury Records to lease and reissue a 1958 Benny Barnes performance originally recorded at Gold Star—the single

“Yearning” (#71806). This decision paid off nicely, for the salvaged recording (of a song written by Eddie Eddings and George Jones) soon became another

Billboard

country chart hit, rising as high as the number twenty-two spot.

Over the next few years D Records remained in operation, but its success waned. Revolutionary changes in musical tastes concerning artists and repertoire were largely responsible perhaps, as Daily never fully accepted the hegemony of rock ’n’ roll, and he had nothing but disdain for the hippie types who were starting to dominate the genre. Though he would stay active with his publishing company and other concerns, he gradually ceased his involvement in D Records productions around 1965. By that time he was in his sixties and probably inclined to enjoy the proceeds of his many profi table years in the music business (though he continued to produce George Jones records in Nashville through February 1971). However, in the twenty-fi rst century his grandson, Wes Daily, would revive the label name for his own productions of new recordings of Texas country music.

Similarly inching toward retirement was Quinn, Daily’s favorite Houston studio owner. Following his long run of engineering sessions for Daily and others, by 1963 he was reducing his role in studio operations, where he would eventually serve only as landlord before ultimately selling and entrusting the Gold Star legacy to new ownership. As musician Glenn Barber sums it up,

“Bill recorded in that big room for a few years and then retired in the early

’60s and leased the place to J. L. Patterson and lived in his house next door.

He would come over pretty often and watch things but didn’t have much to do with anything.”

An era was passing in Texas and beyond—that wild time in the mid-twentieth century when the fi rst generation of maverick studio owners and old-school independent record producers such as Quinn and Daily could collaborate with young talent and limited budgets in hopes of making a hit.

d a i ly ’ s d o m i n a n c e a n d d r e c o r d s

8 1

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 81

1/26/10 1:12:14 PM

9

Little Labels

b l u e s , c o u n t ry, a n d s h a r k s

hile the hundreds of sessions

produced by Pappy

Daily had dominated much of the Gold Star Studios sched-

ule during the late 1950s and early ’60s, proprietor Bill Quinn certainly did have other clients. Some of those were small label owners trying to replicate the commercial success that Daily had achieved with Starday and D Records. Others were individuals, bands, or loose affi liations of people collaborating on a common music project—representing a widening diversity of genres. Some may have even been con artists playing the so-called “song-sharking” game. And of course, there were also various high school or college marching or stage bands, which utilized the big room expansion. Whichever the case, for many musicians who came to Gold Star Studios to record during this era, it was an initiation experience—the fi rst time they ever cut studio tracks. Some of those performers went on to establish famous careers in music.

Of all the record company owners who rented Quinn’s space and services, the only one who could rival Daily’s clout was the African American mogul Don Robey. He owned fi ve Houston-based labels between 1949 and 1973—

and his Gold Star Studios connection is explored more fully in Chapter 11.

Most of the rest had far less success. Yet even among those, there were several historically signifi cant recordings.

For instance, one aspiring independent record company owner was the musician Henry Hayes (b. 1924). Though he had a distinguished thirty-year career as an educator in public schools, Hayes also recorded on many Houston sessions, usually performing on saxophone, with his own band. The resulting singles were released on various labels, including Quinn’s old Gold Star imprint, as well as Savoy, Peacock, Mercury, and others.

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 82

1/26/10 1:12:14 PM

Quinn had engineered Hayes’s very fi rst session as a bandleader, staged at the original Telephone Road site in 1947 or ’48—that is, right around the time that Quinn had started recording black men playing the blues. The result was a 78 rpm Gold Star Records single (#633) off ering two Hayes originals,

“Bowlegged Angeline” and “Baby Girl Blues,” with the performance credited simply to Henry Hayes and His Band. On some of the subsequent recordings for other labels, Hayes led his group (billed variously as the Four Kings, the Rhythm Kings, or the Henry Hayes Orchestra) as the backing ensemble for his protégé, piano-playing vocalist Elmore Nixon (1933–1973), or other singers.

However, Hayes truly made his mark on recording history when he and a partner, M. L. Young, launched their own “look-see” label, Kangaroo Records.

In Roger Wood’s book

Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues,

Hayes sums up their start:

A friend of mine . . . was also a music teacher, . . . So we decided that we was going to put our funds together and start a little record label. . . . And the idea was to put out records on diff erent talent, build ’em up, get some company interested, and then get a lease with them. . . . Kangaroo Records, that was my idea, Kangaroo Records—because it jumped!

Because Gold Star Studios was well established, relatively inexpensive, already familiar to Hayes, and close to the Third Ward (where he and most of his musicians resided), it was a natural site for those Kangaroo Records sessions. And Quinn was manning the booth when Hayes went there in the spring of 1958 to make the fi rst recordings of two postwar masters of Texas blues guitar, Albert Collins (1932–1993) and Joe Hughes (1937–2003).

Those sessions yielded the debut singles for both artists, issued by Kangaroo Records on 45 rpm discs: “The Freeze” (#103) backed with “Collins Shuffl

e” (#104) by Albert Collins and His Rhythm Rockers, as well as “I Can’t Go On This Way” (#105) backed with “Make Me Dance Little Ant” (#106) by Joe Hughes and His Orchestra. The Hughes record was reviewed in

Billboard

magazine in June 1959, but remains an obscurity to all but the most informed fans (who often cite it nonetheless as “Ants in My Pants”). Today its main import lies in its status as the earliest recording by an ultimately widely admired blues artist—as London-based writer Paul Wadey puts it, “a favourite amongst European audiences.”

On the other hand, “The Freeze,” a magical instrumental groove, soon became a regional hit that even reportedly inspired a local dance craze. Moreover, it served as Collins’s signature tune throughout the rest of his career, which would escalate to international blues superstardom by his fi nal decade. Its potency also triggered a succession of various other cold-themed metaphors

l i t t l e l a b e l s

8 3

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 83

1/26/10 1:12:14 PM

that Collins would employ to defi ne his guitar playing—what he called “ice picking”—including later album titles such as

Iceman,

Frostbite,

Cold Snap,

Deep Freeze,

and

Don’t Lose Your Cool,

to cite only a few. Today “The Freeze” is generally considered a modern blues electric guitar classic.

But according to both Hayes and Hughes, the presence of Collins at that session was a fl uke. The only plan for that day was to record Hughes and a local female vocal group, the Dolls. However, as Hughes was preparing to depart for the scheduled morning studio session, he realized in a panic that he had left his only guitar at Shady’s Playhouse, a Third Ward club where he gigged each night. When he raced to that venue only to fi nd it locked and empty, he turned to his friend Collins, who then resided less than a block away. As Hughes puts it in another interview from

Down in Houston,

“So I had Albert go out there with me, and that’s how ‘The Freeze’ got cut, by accident. I went by there and got his guitar and took him to the studio.”

Hayes, in the same book, picks up the story from there:

See, I was the producer in the studio . . . and Albert came along with Joe Hughes . . . So the piano player that used to play with Albert told me, “Man, Albert has a number he’s playing out at the clubs—boy, people are going wild about it! Man, you’ve got to hear that number.”

So Albert came out that day, so when we got through recording the others, I told him, I say, “Albert, I heard about this number ‘Freeze.’ . . . A lot of people [have] been going wild for it in the clubs. . . . They’ve been telling me about it, and you haven’t recorded it with anybody. Do you want to record it with me?”