How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? (24 page)

Read How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Let’s get one issue out of the way immediately. Even the largest beverage producers (or “fillers,” as they are known in the canning industry) don’t make their own cans. A company like Coca-Cola has many different suppliers. And these canners may have many plants designed to produce cans of slightly different composition and dimensions.

Jeff Solomon-Hess, executive editor of

Recycling Today

, reminds us that not all beverage cans are made of aluminum only:

Manufacturers commonly produce two types of beverage cans today: all aluminum and bi-metal. The all aluminum can crushes slightly easier because of its thinner construction. The bi-metal can consist of a steel body and an aluminum top. While steel technology allows for much thinner construction than in the past, the steel cans remain slightly thicker and harder to crush.

William B. Frank, of the Alcoa Technical Center, points out that the “trained consumer” can differentiate between the two types of cans:

The steel can has a matte finish on the bottom and a “stiff” side-wall; the aluminum can is shiny on the bottom and is less stiff after opening. A sure way to distinguish a steel can from an aluminum can is to see whether a small magnet will stick to the body or bottom of the can. Ferromagnetism is used to separate steel cans from aluminum cans in recycling of UBCs [used beverage cans].

We don’t mean to imply that all aluminum cans are created equally. Indeed, off the top of his head, E.J. Westerman, manager of can technology at Kaiser Aluminum, listed five reasons why all-aluminum cans might vary in crushability:

1) There are small differences in diameters of cans (e.g., Coors-type cans are 2 9/16″, while most other American cans are 2 11/16″).

2) Fillers give aluminum producers different requirements for alloy strength and composition.

3) Aluminum producers vary the wall thicknesses of the cans from about 0.0039″ to approximately 0.0042″.

4) Cans can vary in “wall thickness gradation” at the neck and base of the can, which can affect the point at which “column buckling” begins when a can is crushed.

5) The end or lid diameter and thickness can have a great impact upon crushability, particularly if the can is not crushed in the axial direction.

Solomon-Hess feels that the role of the crusher cannot be underestimated:

Most people place the can on end and step on it. If you step on it with a rubber sole shoe (such as a sneaker), your foot sometimes forms an airtight seal. This results in the inside air pressure of the can making it more rigid, and again, harder to crush. Tilting your foot slightly and allowing the air to escape or laying the can on its side makes it crush much easier.

And don’t forget the condition of the can itself. We have found ourselves, often unconsciously, squeezing or popping aluminum cans. As soon as you mess with the structural integrity of the container, it becomes much easier to crush. Solomon-Hess even offers an experiment that you can do at home (children under eighteen, please ask your parents for permission); for reasons too obvious to explain, this experiment may best be conducted outdoors:

If you put a couple of small dents in the can, it requires much less pressure to crush, so people who routinely “pop” the sides of cans as they drink from them find the empty cans easier to crush. For a dramatic example, try this experiment.

Take an empty soda can and place it upright on a hard floor (concrete works best) and ask someone who weighs under 150 pounds to very carefully place his or her full weight on the can with one foot and balance there. Most cans will support such a weight. Now take two pencils and simultaneously tap opposite sides of the can with a firm motion. The resulting dimples cause the can to quickly collapse by creating weak spots in the can’s structure. The effect is the same as scoring a sheet of glass in order to break it cleanly.

Not quite the same—you don’t need a sponge to clean up after breaking a sheet of glass.

Submitted by Roy L. Youngblood of Oceanside, California

.

Why

Are Pigs Roasted with an Apple in Their Mouth?

Is this the first reference book in history to devote three chapters to the appearance of cooked pork products? Maybe so, but we follow the lead of our readers, and pig pulchritude seems to be very much on your minds.

Unfortunately, we have not gotten to first base in answering how this practice originated. But the same pork experts who guided us before are quick to assure us that if an apple was put in the suckling pig’s mouth before roasting, it would quickly turn to a texture more like apple sauce than apples. The pristine apple is put in the pig’s mouth after it is removed from the spit.

So the apple is purely a decorative item, perhaps inserted out of a sense of loss of the aforementioned checkerboard pattern on hams. Tonya Parravano, of the National Live Stock & Meat Board, told

Imponderables

that most recipes

suggest placing a small block of wood in the pig’s mouth before roasting to brace it so an apple can be inserted later. Cranberries or cherries are often used in the eye sockets and some like to give the pig a collar of cranberries, parsley, or flowers.

The poor pig, whose very name conjures up filth and sweat in common parlance, is subjected to even greater indignities before it is consumed.

Submitted by Christine Whitsett of Marion, Alabama

.

Why

Do Many Streets and Sidewalks Glitter? Is There a Secret Glittery Ingredient?

Two main ingredients create the glittering appearance of our concrete and asphalt roadway surfaces: natural rocks and glass. When it comes to asphalt and concrete, the contents are always hybrids, mixes of stones, sand, petroleum derivatives, and “fillers,” ingredients that aren’t necessary for the integrity of the pavement but provide bulk—the construction equivalent of Hamburger Helper.

Sand, glass, silicon, and many natural stones, such as quartz, all glitter. According to Jim Wright, of the New York State Department of Transportation, glass is included in roadways as a way of recycling used byproducts. Other fillers, such as used tires, are thrown in to the mix as a way of keeping solid waste dumps from looking like canyons exclusively devoted to showcasing beaten-down, giant chocolate doughnut lookalikes.

Construction engineers are sensitive to the aesthetics of streets and sidewalks. Billy Higgins, director of congressional relations at the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, told

Imponderables

that glass is often used primarily to make surfaces more attractive. For example, Higgins says that concrete sidewalks routinely are smoothed down with a rotary blade to allow the shiny surfaces to show off to best effect.

Portland cement, a mix made primarily of limestone and clay, becomes a particularly glittery surface when it bonds with sand and other filler agents to become concrete. Portland cement concrete becomes shinier and shinier as it is used, as Thomas Deen, executive director of the Transportation Research Board of the National Research Council, explains:

Some of the aggregate used in portland cement concrete is like a natural mirror; that is, it reflects light. In theory, all aggregate in concrete is completely coated with cement. However, the aggregate on the very top surface of the street or sidewalk will lose part of that coating due to the weathering and vehicular or pedestrian traffic. Once exposed, the light from the sun, headlights, street lights, or other sources bounces off the tiny surfaces of the aggregate, causing the streets and sidewalks to glitter.

Submitted by Sherry Spitzer of San Francisco, California

.

Why

Hasn’t Beer Been Marketed in Plastic Bottles Like Soft Drinks?

Now that the marketing of soda pop in glass bottles has pretty much gone the way of the dodo bird, we contacted several beer experts to find out why the beer industry hasn’t followed suit. The reasons are many; let us count the ways:

1. Most beer sold in North America is pasteurized. According to Ron Siebel, president of beer technology giant J.E. Siebel Sons, plastic bottles cannot withstand the heat during the pasteurization process. Plastics have gained in strength, but the type of plastic bottle necessary to endure pasteurization would be quite expensive.

John T. McCabe, technical director of the Master Brewers Association of the Americas, told

Imponderables

that in the United Kingdom, where most beer is not pasteurized, a few breweries are marketing beer in plastic bottles. Siebel indicated that he would not be surprised if an American brewer of nonpasteurized (bottled) “draft” beer doesn’t try plastic packaging eventually.

2. Breweries want as long a shelf life as possible for their beers. According to Siebel and McCabe, carbon dioxide can diffuse through plastic and escape into the air, while oxygen can penetrate the bottle, resulting in a flat beverage. Glass is much less porous than plastic.

3. Sunlight can harm beer. Siebel indicates that beer exposed to the sun can develop a “skunky” taste and smell; this is why many beers are sold in dark and semi-opaque bottles.

4. Appearance. We have no market research to support this theory, but we wouldn’t guess that beer would be the most delectable looking beverage to the consumer roving the supermarket or liquor store aisle.

One might think that breweries would kill to package their product like soft drinks. Could you imagine the happy faces of beer executives as they watched consumers lugging home three-liter plastic bottles of suds?

Submitted by John Lind of Ayer, Massachusetts

.

Why

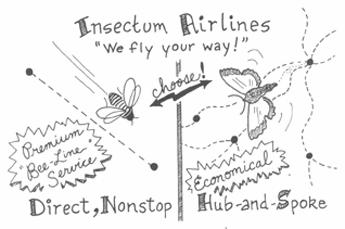

Do Some Insects Fly in a Straight Line While Others Tend to Zigzag?

As entomologist Randy Morgan of the Cincinnati Insectarium puts it, “Flight behavior is an optimization of the need to avoid predators while searching for food and mates.” Gee, if Morgan just eliminated the word “flight” and changed the word “predators” to “creditors,” he’d be describing

our

lives.

Notwithstanding the cheap joke, Morgan describes the problems of evaluating the flight patterns of insects. An insect might zigzag because it is trying to avoid an enemy or because it doesn’t have an accurate sighting of a potential food source. A predatory insect might be flying in a straight line because it is unafraid of other predators or because it is trying to “make time” when migrating; the same insect in search of food might zigzag if its target wasn’t yet selected.

Leslie Saul, Insect Zoo director at the San Francisco Zoological Society, wrote

Imponderables

that the observable flying patterns of different insects can vary dramatically: