How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? (22 page)

Read How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Submitted by Sarah Robertson of Sun Valley, Nevada

.

If

Grapes Are Both Green and Purple, Why Are Grape Jellies Always Purple?

If you read our first book of Imponderables (entitled, appropriately enough,

Imponderables

), you know how they make white wine out of black grapes. But for those of you who aren’t yet fully literate, we’ll reiterate: The juice from grapes of any color is a wan, whitish or yellowish hue. White wine is the color of that juice. Red wine combines the juice of the grape along with its skin. The color of the skin, not the juice, gives red wine its characteristic shade.

If you want to prove this premise, go out to your local supermarket or produce store and crush a few red and green grapes into empty containers—you’ll be surprised at how similar the colors of the liquids are. But throw grapes with skin into a blender or food processor, and you’ll have a very different color. One more suggestion: We recommend using seedless grapes.

Ever since 1918, when Welch’s started marketing grapelade, a precursor of the jellies soon to follow, the company used Concord grapes exclusively. By the time the company pioneered the mass distribution of jelly, it was already established in the juice business: Welch’s introduced grape juice in 1869, using the same dark Concord grapes. James Weidman III, vice-president of corporate communications for Welch’s, told us that the characteristic color of Welch’s grape jelly comes from the purple skin of the Concord grape, although the pulp of the Concord grape is white: “Because the basic ingredient in grape jelly is juice, the jelly is therefore purple.”

Megan Haugood, account manager at the California Table Grape Commission, told us that consumers now expect and demand the purple color established by Welch’s and would be uncomfortable with the appearance of a green grape jelly, even assuming a jelly could be made from green grapes that tasted as good. So all of Welch’s competitors adopted the same bright color for their grape jellies.

We asked Sandy Davenport, of the International Jelly and Preserve Association, whether her organization was aware of any green jellies in the marketplace. She started looking through her six-hundred-page directory, finding marketers of rhubarb jelly, partridge berry jelly, California plum jelly, and, of course, kiwifruit jelly. But no green grape jellies in sight. Most of the experts we consulted felt that green grapes are considerably blander in taste and would be unlikely to gain a foothold in the marketplace, even if youngsters could tolerate the idea of eating peanut butter and green jelly sandwiches.

Submitted by Jeff Thomsen of Naperville, Illinois.

Why

Didn’t Fire Trucks Have Roofs Until Long After Cars and Trucks Had Roofs?

The first fire wagons in America were not motorized. They weren’t even horse-drawn. They were drawn by humans. Bruce Hisley, instructor at the National Fire Academy, told

Imponderables

that verifiable records of human-drawn fire engines show that they were in use as late as 1840. Horse-drawn open carriages were then the rule until motorized coaches were introduced in 1912.

By today’s standards, the early motorized fire trucks were far from state of the art. Not only were they topless, but they lacked windshields. Early designers didn’t realize the environmental impact of greater speeds upon fire crews, especially the driver. Although drivers soon put on goggles to help fight off the wind, rain, and snow to which they were exposed, the addition of windshields was a major advance for safety and driver comfort. So was another afterthought: doors on the sides of the cab.

Of course, it was the rule for the crew to stand on the outside of the truck during runs, exposing them to further unsafe conditions. Although roofs and closed cabs were introduced in the late 1920s or early 1930s, many firefighters continued to ride on the outside. As David Cerull, of the Fire Collectors Club, puts it: “When it comes to change in the fire service, the attitude that prevails is: ‘If we did not have them before, why should we have them now?’”

Fire departments did have some legitimate arguments against the covered cabs. Martin F. Henry, assistant vice-president of the National Fire Protection Association, told

Imponderables

that many fire departments, upon receiving covers for their fire trucks, promptly removed them. Why?

The thinking at the time was that the open cab provided an ability to see the fire building in an unrestricted fashion. Ladder companies, it was thought, would have a better opportunity to know where to place the aerial if they could see the building from the cab.

This objection was particularly strong in urban areas. Cerull points out that when approaching a fire in a highrise, the company could see the upper floors and roofs more easily. Eventually, the “sun roof” solved this problem.

The other complaint about early roofs was that the roofs themselves were fire hazards. Arthur Douglas, of fire equipment manufacturer Lowell Corporation, told us that many of the roofs were protected by weatherproofing, sometimes wood covered with a treated fabric. “Both of these materials were, of course, flammable, thus a high risk on a firefighting unit.” The metal roof obviously solved this argument against the closed cab.

So why didn’t the changeover occur more quickly? One reason, besides sure inertia, opines Henry, is that the life span of fire trucks is twenty to twenty-five years. Many departments were loath to abandon functioning apparatus. And although many firefighters enjoyed riding the tail-board, statistics accumulated, to no one’s surprise, proving that the outside of a truck moving at forty miles per hour wasn’t the best place to be during an accident.

But perhaps the precipitating factor in closing cabs is a sadder commentary on our culture than a disregard for safety, as Martin Henry explains:

Open cabs came to an abrupt halt in major metropolitan areas when it became fashionable to hurl objects at firefighters. All riding positions were quickly enclosed.

Submitted by Scott Douglas Burke of Charlestown, Maryland

.

Why

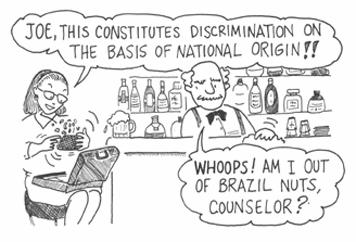

Are There So Few Brazil Nuts in Mixed Nuts Assortments?

We contacted a slew of nut authorities and quickly realized that the ratio of various nuts in an assortment is

serious business

. The industry rule of thumb is that there is never less than 2 percent by weight of any type of nut in a mixed-nut assortment, but how do they arrive at the proper proportion? Focus groups, of course. Nut marketers attract roving hordes off the street, sit them down at a table, and find out what people’s deepest fears, needs, and fantasies about mixed nut assortments truly are.

And here’s why Brazil nuts get the shaft:

1.

People don’t like them that much

. If Brazil nuts were popular, you’d see the big nut companies, like Planters, selling whole jars of Brazil nuts. They don’t because an insufficient number of consumers would buy them. As one nut expert so accurately put it: “Generally, the last nut remaining in the nut bowl after favorites have been picked by consumers in the Brazil nut.” A representative of Planters Peanuts who preferred to remain anonymous assured us that cashews, pecans, and almonds are all preferred over Brazil nuts.

2.

People don’t like the color of Brazil nuts

. Walter Payne, of Blue Diamond, wrote

Imponderables

that it is difficult and quite expensive to take the skin off (i.e., blanch) Brazil nuts. Consumers prefer lighter colored nuts, which limits the distribution ratio of the Brazil nuts. Payne notes that in assortments offering blanched Brazil nuts, “the Brazil population in the mix is much higher.”

3.

Brazil nuts are too big

. If you put more of them in an assortment, they would physically dominate the mix.

4.

Brazil nuts are expensive

. We contacted the Peanut Factory, a Rome, Georgia, marketer of many mixed assortments. The folks at the Factory assured us that when determining a ratio of nuts in a mix, there is always a balance between popularity and price. Brazil nuts, imported from Brazil, Peru, or Bolivia, are just too expensive to justify increasing their proportion. If consumers wanted more Brazil nuts, they would complain. But no one we contacted showed the slightest indication that they’ve ever been confronted with angry consumers demanding more Brazil nuts.

We don’t know why you asked this question, Michele, but we hope you are satisfied. If you aren’t, I’m sure you derive pleasure from being invited to many parties, where your main role is to eat all the Brazil nuts left by more conventional partygoers.

Submitted by Michele Baerri of Leonie, New Jersey

.

Stop the Presses

. Days before we submitted this manuscript, we heard from Kimberly J. Cutchins, president of the National Peanut Council:

As the National Peanut Council, we do not represent other nuts. However, I did call one of our members, Planters, to get a response to this question. A pound of peanuts costs between 35 cents and 70 cents, depending on the size and variety. Brazil nuts cost approximately $1.25 per pound. Although the difference in price of the nuts is significant, it is not the reason there are so few Brazil nuts in mixed nut assortments. According to Planters, it is consumer preference that determines the ratio of nuts.

So far, Cutchins merely confirms our research. But then she dropped the bombshell:

Just recently, Planters has increased the number of Brazil nuts in their assortment to reflect consumer demand.

There you are, Michele. An unprecedented boomlet for Brazil nuts has changed the equation. Can filberts be far behind?

Why

Do American Doors Have Round Door Knobs, While Many Other Countries Use Handles?

Our correspondents wonder why the knob is virtually ubiquitous when it is much more inconvenient than the handle. Anyone who has ever arrived home carrying three sacks of groceries, with an eight-year-old child and a dog in tow, quickly grasps the notion that it would be far easier to pull down a lever with a loose elbow than to grasp a knob tightly and twist.

All of the hardware sources we contacted indicated that the primary reason knobs are more popular in the United States is simply because customers prefer their looks. Richard Hudnut, product standards coordinator for the Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association, told us that knobs are also easier to manufacture and thus usually cheaper for the consumer.

Joe Lesniak, technical director of the Door and Hardware Institute, says that handles (or “levers,” as they are known in the trade) are making a comeback, for at least two reasons. Just as tastes in hemlines vary for no discernible reason, so do preferences for door finishings. As this book is being written, short skirts and door handles are in vogue. But more importantly, the soon to be enforced Americans with Disabilities Act and the Fair Housing Act are going to change Americans’ knob habit indefinitely. This legislation mandates that doors in buildings other than one-and two-family dwellings must contain handles and pulls that are easy to activate with one hand and that don’t need to be tightly held.