How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? (18 page)

Read How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? Online

Authors: David Feldman

You

do

stay out in the sun too long, but you’re surprised that you haven’t burned too badly. Still, you feel a heaviness on your skin. That night, you start feeling a burning sensation.

The next morning, you wake up and go into the bathroom. You look in the mirror. George Hamilton is staring back at you. Don’t you hate when that happens?

Despite our association of sunburn and tanning with fun in the sun, sunburn is, to quote U.S. Army dermatologist Col. John R. Cook, nothing more than “an injury to the skin caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation.” The sun’s ultraviolet rays, ranging in length from 200 to 400 nanometers, invisible to the naked eye, are also responsible for skin cancer. Luckily for us, much of the damaging effects of the sun is filtered by our ozone layer.

Actually, some of us do redden quickly after exposure to the sun, but Samuel T. Selden, Chesapeake, Virginia, dermatologist, told us that this

initial “blush” is primarily due to the heat, with blood going through the skin in an effort to radiate the heat to the outside, reducing the core temperature.

This initial reaction is not the burn itself. In most cases, the peak burn is reached fifteen to twenty-four hours after exposure. A whole series of events causes the erythema (reddening) of the skin, after a prolonged exposure to the sun:

1. In an attempt to repair damaged cells, vessels widen in order to rush blood to the surface of the skin. As biophysicist Joe Doyle puts it, “The redness we see is not actually the burn, but rather the blood that has come to repair the cells that have burned.” This process, called vasodilation, is prompted by the release of one or more chemicals, such as kinins, setotonins, and histamines.

2. Capillaries break down and slowly leak blood.

3. Exposure to the sun stimulates the skin to manufacture more melanin, the pigment that makes us appear darker (darker-skinned people, in general, can better withstand exposure to the sun, and are more likely to tan than burn).

4. Prostaglandins, fatty acid compounds, are released after cells are damaged by the sun, and play some role in the delay of sunburns, but researchers don’t know yet exactly how this works.

All four of these processes take time and explain the delayed appearance of sunburn. The rate at which an individual will tan is dependent upon the skin type (the amount of melanin already in the skin), the wavelength of the ultraviolet rays, the volume of time in the sun, and the time of day. (If you are tanning at any time other than office hours—9:00

A.M

. to 5:00

P.M

.—you are unlikely to burn.)

Even after erythema occurs, your body attempts to heal you. Peeling, for example, can be an important defense mechanism, as Dr. Selden explains:

The peeling that takes place as the sunburn progresses is the skin’s effort to thicken up in preparation for further sun exposure. The skin thickens and darkens with each sun exposure, but some individuals, lacking the ability to tan, suffer sunburns with each sun exposure.

One dermatologist, Joseph P. Bark, of Lexington, Kentucky, told us that the delayed burning effect is responsible for much of the severe skin damage he sees in his practice. Sunbathers think that if they haven’t burned yet, they can continue sitting in the sun, but there is no way to gauge how much damage one has incurred simply by examining the color or extent of the erythema. To Bark, this is like saying there is no fire when we detect smoke, but no flames. Long before sunburns appear, a doctor can find cell damage by examining samples through a microscope.

Submitted by Launi Rountry of Brockton, Massachusetts

.

No, they are not practicing how to bang on an opponent’s head—the answer is far more benign.

In most sports, such as baseball, football, and basketball, play is stopped when substitutions are made. But ice hockey allows unlimited substitution

while the game is in progress

, one of the features that makes hockey such a fast-paced game.

It is the goalie’s job to be a dispatcher, announcing to his teammates when traffic patterns are changing on the ice. For example, a minor penalty involves the offender serving two minutes in the penalty box. Some goalies bang the ice to signal to teammates that they are now at even strength.

But according to Herb Hammond, eastern regional scout for the New York Rangers, the banging is most commonly used by goalies whose teams are on a power play (a one-man advantage):

It is his way of signaling to his teammates on the ice that the penalty is over and that they are no longer on the power play. Because the players are working hard and cannot see the scoreboard, the goalie is instructed by his coach to bang the stick on the ice to give them a signal they can hear.

Submitted by Daniell Bull of Alexandria, Virginia

.

The substance that resembles red paint probably

is

red paint. Or fingernail polish. Or red lacquer. Or the red dye from a marking pen.

Why is it there? According to Brenda F. Gatling, chief, executive secretariat of the United States Mint, the coins usually are deliberately “defaced” by interest groups for “special promotions, often to show the effect upon a local economy of a particular employer.” Other times, political or special interest groups will mark coins to indicate their economic clout. Why quarters? As the largest and most valuable coin in heavy circulation, the marking is most visible and most likely to be noticed.

Some businesses—the most common culprits are bars and restaurants—mark quarters. Employees are then allowed to take “red quarters” out of the cash register and plunk them into jukeboxes. When the coins are emptied from the jukebox, the red quarters are retrieved, put back into the register, and the day’s income reconciled.

Submitted by Bill O’Donnell of Eminence, Missouri. Thanks also to Thomas Frick of Los Angeles, California, and Michael Kinch of Corvallis, Oregon

.

Why

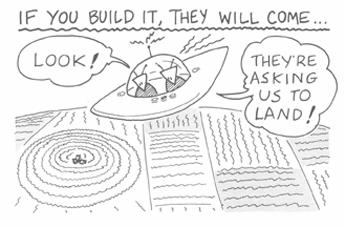

Are So Many Farm Plots Now Circular Instead of Squarish?

Our peripatetic correspondent Bonnie Gellas first noted this Imponderable while on frequent airplane trips. The neat checkerboard patterns of farm plots that she remembered from earlier days have transformed themselves into pie-plots. Are there hordes of agricultural exterior decorators convincing farmers that round is hip and rectangular is square?

We’re afraid the answer is considerably more prosaic. The round farm plots are the result of modern irrigation technology—specifically, “center pivot irrigation” systems. Dale Vanderholm, associate dean for agricultural research at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, told

Imponderables

that one of the problems with squarish plots was the expense required to water them. They required lateral movement systems, in which one huge pipe the length (or width) of the land traveled back and forth in order to irrigate the entire field.

Center pivot systems, on the other hand, require only one water source, at the center of each plot. Pipes must still move, but they travel only the relatively short distance around the “pivots.” According to Lee Grant, of the University of Maryland’s Agricultural Engineering Department:

The traveling system moves on “tractors,” spaced at intervals along the irrigation pipe. The “tractors” are supported by pairs of tractor type tires arranged one in front of the other. Motors driven by the flowing water turn the tires to pivot the irrigation pipe around the field.

We asked Vanderholm what farmers did with the “corners” of the circle, the small portions of land outside the reach of the spray. Usually farmers plant crops that don’t require irrigation or don’t farm that area. If they want to spend the money, they can also buy auxiliary arms, which can water areas beyond the reach of the center pivot.

According to Vanderholm, center pivot systems are most popular in the high plains states, just where you would likely be looking out the window on cross-country flights, bored out of your mind, craving sensory input, and seeking any alternative to the airplane food, movie, or seatmate.

Submitted by Bonnie Gellas of New York, New York. Thanks also to Gloria Klinesmith of Waukegan, Illinois

.

These four states chose to call themselves commonwealths, yet trying to find a reason why they did so is a futile exercise. By all accounts, the word “state” preceded “commonwealth.” Etymologists argue over whether the term predated medieval Europe, but all agree that the concept of “state” was well established by then. Most social scientists define “state” as any discrete political unit that has a fixed territory and a government with legal or political sovereignty over it. Theoretically, though, a “state,” in its abstract form, could be taken over by a military dictator and retain its “stateness.”

The notion of a commonwealth can be traced directly to the social philosophers of the seventeenth century, particularly Thomas Hobbes of England. He argued that the government should work for the “common weal” (or welfare) of the governed. These Hobbesian principles were articulated by John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, in 1637:

the essential form of a common weale or body politic, such as this, is the consent of a certaine companie of people to cohabitate together under one government for their mutual safety and welfare.

All the historians we contacted thought that the four states called themselves “commonwealths” to emphasize their freedom from the monarchy in England and the republican nature of the government, while also indicating there was no evidence that they consciously tried to separate themselves from the other colonies that deemed themselves “states.” Indeed, looking over the constitutions of the four commonwealths, we see that the crafters of the documents often used “commonwealth” and “state” interchangeably. For example, while the constitution of Virginia refers in several places to “the people of the Commonwealth” and “government for this Commonwealth,” it also declares that “this State shall ever remain a member of the United States of America.”

The Massachusetts Constitution, in the “Frame of Government” section, indicates its purpose:

The people inhabiting the territory formerly called the province of Massachusetts Bay do hereby solemnly and mutually agree with each other to form themselves into a free, sovereign, and independent body-politic or State, by the name of the commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Of course, as far as the federal government is concerned, commonwealths are just like any other states, with all the privileges, rights, and taxes due thereto.

Submitted by Randall S. Varner of Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. Thanks also to Rick De Witt of Erie, Pennsylvania, and William Lee of Melville, New York

.

How

Do Engineers Decide Where to Put Curves on Highways?

We don’t expect to jolt any of you by announcing that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. So one might think that it would be cheapest, most efficient, and most convenient to decide where a highway starts and where it ends, and then construct a straight roadway and link the two. But

one

would be wrong.