How Music Works (10 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

the gear ends up being lit as much as the performers. To mitigate this a little bit I had all the metal hardware (cymbal stands and keyboard racks) painted

matte black so that it wouldn’t outshine the musicians. We hid the guitar

amps under the riders that the backing band played on, so those were invisible too. Wearing gray suits seemed to be the best of both worlds, and by planning it in advance, we knew there would at least be consistent lighting from night to night. Typically a musician or singer might decide to wear their white or black shirt on a given night, and they’d end up either glowing brighter than everyone else or be rendered invisible. We avoided that problem.

J

54 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

On all of our previous tours we’d maintained the lighting dogma left over

from CBGB: white light, on at the top of the show and off at the end. But I

felt it was time to break away from that a little bit. I still confined the lighting to white, though now white in all its possibilities, permutations, and

combinations. There were no colored gels as such, but we did use fluores-

cent bulbs, movie lights, shadows, handheld lights, work lights, household

lamps, and floor lights—each of which had a particular quality of its own,

but were still what we might consider

white

. I brought in a lighting designer, Beverly Emmons, whose work I’d seen in a piece by the director Robert

Wilson. I showed her the storyboards and explained the concept, and she

knew exactly how to achieve the desired effects, which lighting instruments

to use, and how to rig them.

I had become excited by the downtown New York theater scene. Robert

Wilson, Mabou Mines, and the Wooster Group in particular were all experi-

menting with new ways of putting things on stage and presenting them,

experiments that to my eyes were close to the Asian theater forms and ritu-

als that had recently inspired me.K

What they were all doing was as exciting for me as when I’d first heard

pop music as an adolescent, or when the anything-goes attitude of the

punk and post-punk scene flourished. I invited JoAnne Akalaitis, one of the

directors involved with Mabou Mines, to look at our early rehearsals and

K

DAV I D BY R N E | 55

give me some notes. There was no staging or lighting yet, but I was curious

whether a more theatrical eye might see something I was missing, or sug-

gest a better way to do something.

To further complicate matters, I decided to make the show completely

transparent. I would show how everything was done and how it had been put

together. The audience would see each piece of stage gear being put into place and then see, as soon as possible afterward, what that instrument (or type of lighting) did. It seemed like such an obvious idea that I was shocked that I didn’t know of a show (well, a music show) that had done it before.

Following this concept to its natural conclusion meant starting with a bare

stage. The idea was that you’d stare at the emptiness and imagine what might be possible. A single work light would be hanging from the fly space, as it

typically does during rehearsals or when a crew is moving stuff in and out. No glamour and no “show”—although, of course, this was all part of the show.

The idea was that we’d make even more visible what had evolved on the

previous tour, in which we’d often start a set with a few songs performed

with just the four-piece band, and then gradually other musicians would take their places on pre-set keyboard and percussion risers. In this case, though, we’d take the concept further, with each player and the instruments themselves appearing on an empty stage, one after another. So, ideally, when they walked on and began to play or sing, you’d hear what each musician or singer was bringing to the party—added groove elements, keyboard textures, vocal

harmonies. This was done by having their gear on rolling platforms that were hidden in the wings. The platforms would be pushed out by stagehands, and

then the musician would jump into position and remain part of the group

until the end of the show.

Stage and lighting elements would also be carried out by the stagehands:

footlights, lights on stands like they use in movies, slide projectors on scaffolding. Sometimes these lighting instruments would be used right after

their appearance, so you’d immediately see what they did, what effect they

had. When everything was finally in place you’d get to see all the elements

you’d been introduced to used in conjunction with each other. The magician

would show how the trick was done and then do the trick, and my belief was

that this transparency wouldn’t lessen the magic.

Well, that was the idea. A lot of it came from the Asian theater and ritual I’d seen. The operators manipulating the Bunraku puppets in plain sight, assistants 56 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

coming on stage to help a Kabuki actor with a costume transformation, the fact that in Bali one could see the preparation for a scene or ritual, but none of that mattered, none of the force or impact was lost, despite all the spoilers.

There is another way in which pop-music shows resemble both Western

and Eastern classical theater: the audience knows the story already. In classical theater, the director’s interpretation holds a mirror up to the oft-told tale in a way that allows us so see it in a new light. Well, same with pop

concerts. The audience loves to hear songs they’ve heard before, and though

they are most familiar with the recorded versions, they appreciate hearing

what they already know in a new context. They don’t want an immaculate

reproduction of the record, they want it skewed in some way. They want to

see something familiar from a new angle.

As a performing artist, this can be frustrating. We don’t want to be stuck

playing our hits forever, but only playing new, unfamiliar stuff can alienate a crowd—I know, I’ve done it. This situation seems unfair. You would never

go to a movie longing to spend half the evening watching familiar scenes

featuring the actors replayed, with only

a few new ones interspersed. And you’d

L

grow tired of a visual artist or a writer

who merely replicated work they’ve done

before with little variation. But some-

times that is indeed exactly what people

want. In art museums a mixture of the

known, familiar, and new is expected, as

it is in classical concerts. But even within

these confines there’s a lot of wiggle room

in a pop concert. It’s not a rote exercise,

or it doesn’t have to be.

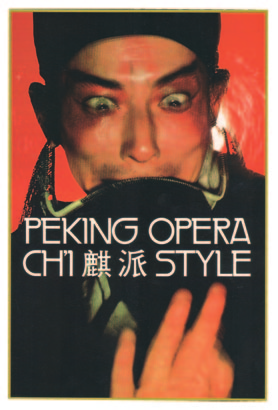

While we were performing the shows

in Los Angeles that would eventually

become the

Stop Making Sense

film, I

invited the late William Chow,L a great

Beijing Opera actor, to see what we were

doing. I’d seen him perform not too long

before, and was curious what he would

make of this stuff. He’d never been to a

DAV I D BY R N E | 57

Western pop show before, though I suspect he’d seen things on TV. The next

day we met for lunch after the show.

William was forthright, blunt maybe; he had no fear that his outsider per-

spective might not be relevant. He told me in great detail what I was “doing wrong” and what I could improve. Surprisingly, to me anyway, his observations were like the adages one might have heard from a vaudevillian, a burlesque

dancer, or a stand-up comedian: certain stage rules appear to be universal.

Some of his comments were about how to make an entrance or how to direct an

audience’s attention. One adage was along the lines of needing to let the audience know you’re going to do something special before you do it. You tip them off and draw their attention to you (and you have to know how to do that in a way that isn’t obvious) or toward whoever is going to do the special thing. It seems counterintuitive in some ways; where’s the surprise if you let the audience in on what’s about to happen? Well, odds are, if you don’t alert them, half the audience will miss it. They’ll blink or be looking elsewhere. Being caught by surprise is, it seems, not good. I’ve made this mistake plenty of times. It doesn’t just apply to stage stuff or to a dramatic vocal moment in performance, either. One can see the application of this rule in film and almost everywhere else. Stand-up comedians probably have lots of similar rules about getting an audience ready for the punch line.

A similar adage was “Tell the audience what you’re going to do, and then

do it.” “Telling” doesn’t mean going to the mic and saying, “Adrian’s going

to do an amazing guitar solo now.” It’s more subtle than that. The directors and editors of horror movies have taught us many such rules, like the sac-rificial victim and the ominous music (which sometimes leads to nothing

the first time, increasing the shock when something actually happens later).

And then while we sit there in the theater anticipating what will happen,

the director can play with those expectations, acknowledging that he or

she knows that we know. There are two conversations going on at the same

time: the story and a conversation about how the story is being told. The

same thing can happen on stage.

The dancing that had emerged organically in the previous tour began to

get increasingly codified. It still emerged out of movement that was impro-

vised in rehearsals, but now I was more confident that if a singer, player, or performer did something spontaneously that worked perfectly for us, it could be repeated without any risk of losing its power and soul. I had confidence

58 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

that this bottom-up approach to making a show would work. Every performer

does this. If something new works one night, well, leave it in. It could be a lighting cue, removing one’s jacket, a vocal embellishment, or smashing a guitar. Anything can eventually grow stale, and one has to be diligent, but when a move or gesture or sound is right, it adds to the emotion and intensity, and each time it’s as real as it was the first time.

Not everyone liked this new approach. The fact that some of the perform-

ers had to hit their marks, or at least come close, didn’t seem very rock and roll to them. But, going back to William Chow’s admonishments, if you’re

going to do something wild and spontaneous, at least “tell” the audience)

ahead of time and do it in the light, or your inspired moment is wasted.

But where does the music fit into all this? Isn’t music the “content” that

should be guiding all this stage business? Well, it seems the juxtaposition

of music and image guides our minds and hearts so that, in the end, which

came first doesn’t matter as much as one might think. A lighting or staging

idea (using household fixtures—a floor lamp, for instance) is paired with a

song (“This Must Be the Place”) and one automatically assumes there’s a

connection. Paired with another lighting effect the song might have seemed

equally suited, but maybe more ominous or even threatening (though that

might have worked, too). We sometimes think we discern cause and effect

simply because things are taking place at the same moment in time, and this

extends beyond the stage. We read into things, find emotional links between

what we see and hear, and to me, these connections are no less true and

honest for not being conceived and developed ahead of time.

This show was the most ambitious thing I’d done. Although the idea was

simple, the fact that every piece of gear had to come on stage for tech check in the afternoon and then be removed again before the show was a lot of work for the crew. But the show was a success; the transparency and conceptual