How Music Works (7 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

DAV I D BY R N E | 39

hair, no rock lights (our instructions to club lighting people were “Turn them all on at the beginning and turn them off at the end”), no rehearsed stage patter (I announced the song titles and said “Thank you” and nothing more), and no singing like a black man. The lyrics too were stripped bare. I told myself I would use no clichéd rock phrases, no “Ohh, baby”s or words that I wouldn’t

use in daily speech, except ironically, or as a reference to another song.

It was mathematics; when you subtract all that unwanted stuff from

something, art or music, what do you have left? Who knows? With the

objectionable bits removed, does it then become more “real”? More honest?

I don’t think so anymore. I eventually realized that the simple act of get-

ting on stage is in itself artificial, but the dogma provided a place to start.

We could at least pretend we had jettisoned our baggage (or other people’s

baggage, as we imagined it) and would therefore be forced to come up with

something new. It wasn’t entirely crazy.

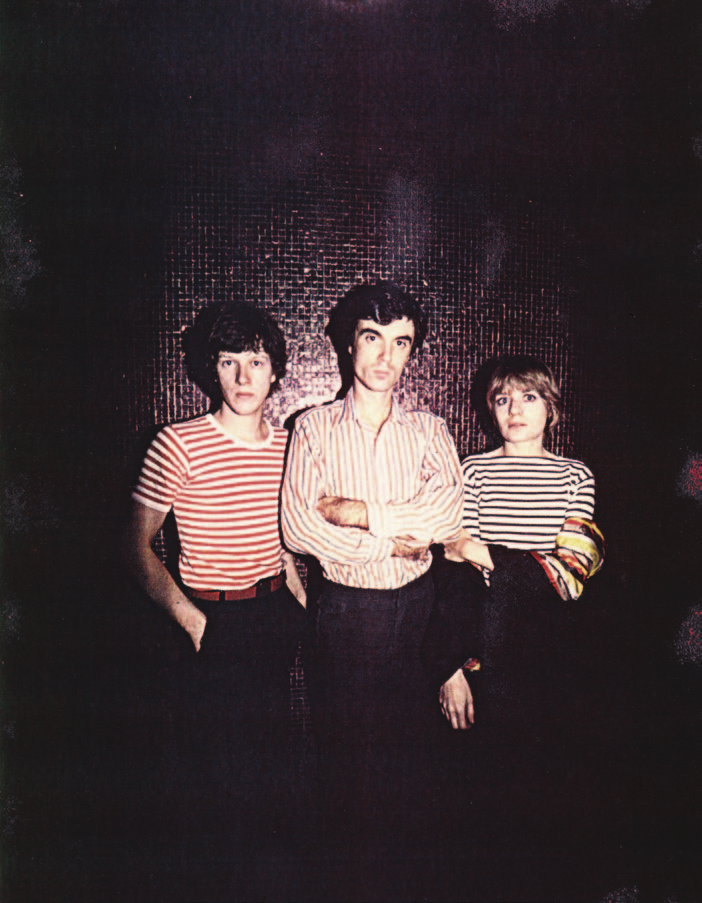

Clothing is part of performance too, but how were we supposed to start

from scratch sartorially? Of course, back then the fact that we were (some-

times) wearing polo shirts both set us apart and branded us as preppies.B

In the nineties, preppy was adopted as a hip-hop look, but back then it

smacked of WASP elitism and privilege, which wasn’t very rock and roll. That wasn’t my background, but I was fascinated by the fact that the old-guard mov-ers and shakers of the United States had an actual look (with approved brands!).

And despite their wealth, the clothing choices made by ye olde masters of the universe weren’t super flattering! They could afford to pay for flattering clothes, but they opted for house dresses and schlubby suits. What’s the story here?!

After leaving funky Baltimore (a city with an eccentric character that had

also come to be defined by race riots and white flight) for art school in little Providence, Rhode Island, I met folks with histories way different from mine, and I found it strange and wonderful. Trying to figure all that out was at least as informative as what I was learning in my classes. Some of these folks had uniforms of a sort—not military- or UPS-style uniforms, but they adhered

fairly rigorously to clothing regimens that were way different than anything I was familiar with. I realized that there were “shows” going on all the time.

The WASP style was often portrayed on TV and in movies as a sort of

archetypical American look, and some of my new friends seemed to subscribe

to it. I decided I’d try it too. I’d tried other looks previously, like Glam dude and Amish geezer, so why not this one?

40 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

DAV I D BY R N E | 41

B

I didn’t stay with it consistently. At one point I decided my look would be, like our musical dogma, stripped down, in the sense that I would attempt to

have no look at all. In my forays outside of bohemia and away from the winos and addicts that littered the Bowery at that time, I realized that most New

York men wore suits, and that this was a kind of uniform that intentionally

eliminated (or was at least intended to eliminate) the possibility of clothing as a statement. Like a school uniform, it was assumed that if everyone looked more or less the same, the focus would be on one’s actions and person and

not on the outward trappings. The intention, I guess, was democratic and

meritorious, though subtle class signals were there.

So in an attempt to look like Mr. Man on the Street I got a cheap polyester

suitC—gray with subtle checks, from one of those downtown discount out-

lets—and I wore that on stage a few times. But it got sweaty under the stage lights, and when I threw it in the washer and dryer at Tina’s brother’s place it shrank down and became unwearable. Before that I used to hang out at CBGB

in a white plastic raincoat and sunglasses. I looked like a flasher!

The preppy look was at least more practical in a packed sweaty club than

plastic or polyester, so I stuck with it for a while. I was aware that our sartorial choice was not without liabilities. We were accused of being dilettantes, and of not being “serious” (read: authentic or pure). My background wasn’t upper class, so this caught me a bit by surprise, and I felt such accusations were a distraction from the music we were making—which was indeed serious, at

least in its attempt to rethink what pop music could be. I soon realized that when it comes to clothing it is next to impossible to find something completely neutral. Every outfit carries cultural baggage of some kind. It took me a while to get a handle on this aspect of performance.

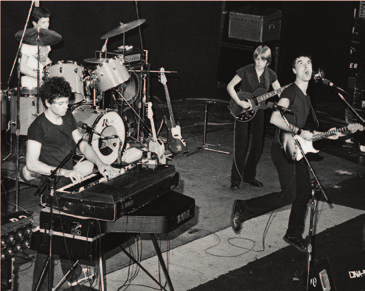

After a couple of years we felt ready to flesh out our

C

sound, to add a little color to our black-and-white draw-

ing. A mutual friend tipped us that a musician named Jerry

Harrison was available. We loved the Modern Lovers demo

record that had recently come out which he’d played on, so

we invited Jerry to sit in. He had some trepidation, hav-

ing been burned by his experience with that band (their

lead singer, Jonathan Richman, dumped the band and went

acoustic folkie just as they were closing in on the brass

ring), so at first Jerry played with us on just a few songs

42 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

during some out-of-town shows. Eventually he took the plunge. As a four-

piece, we suddenly sounded like a real band. The music was still spartan, sparse and squeaky clean, but now there was a roundness to the sound that was more

physically and sonically moving—even slightly sensuous at times, God forbid.

There were other changes. T-shirts and skinny black jeans soon became

the uniform of choice, at least for Jerry and me.D

At that time one couldn’t buy skinny black jeans in the United States—

imagine! But when we played in Paris after our first record came out we

went shopping for le jeans, and, finding them easily, we stocked up. The

French obviously appreciated what they viewed as the proto American Rebel

look more than Americans did. But what’s more American Everyman than

jeans and T-shirts? It was a sexier Everyman than the polyester-suit guy,

and jeans and T-shirts are easy to wash and care for on the road.

But make no mistake—these weren’t ordinary blue jeans. These were

skinny straight-leg black jeans, referencing an earlier generation (much,

much earlier) of rebels and festering youth. These outfits and their silhou-

ettes evoked greasers and rockabilly performers like Eddie Cochran, but also the Beatles and the Stones—before they had a wardrobe budget. Symbolically,

we were getting back to basics.E

Maybe the skinny, dark, stick-figure look alluded to other eras as well, like the tortured emaciated self-portraits of Egon Schiele and stylized bohemian

extremists such as Antonin Artaud. The conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth only

wore black in those days, as did a girlfriend I briefly dated. It was a uni-

form that signified that one was a kind of downtown aesthete; not necessarily nihilistic, but a monk in the bohemian order.

D

E

The retro suits and skinny black ties that became associated with the down-

town music scene—those I just couldn’t figure out. What was that supposed to reference? Was there a noir movie I missed where the guys dressed like this? I’d tried suits, and I wasn’t going back there.

Jerry played keyboards and guitar, and he sang too, so we learned that with

this arsenal we could vary the textures on each song more than we had before.

Texture would became part of the musical content—something that wasn’t

possible with the stripped-down three-piece band. Sometimes Jerry would

play electric piano and sometimes a guitar part, often something contrapuntal to mine. Sometimes one of us would play slide guitar while the other played

chords. Previously we’d desperately attempted to vary the texture from song

to song by having Chris leave his drums and play vibes or having me switch

to acoustic guitar, but before Jerry, our choices were limited. By the time we recorded our first record, in 1976, he had just barely learned our repertoire, but already some flesh was appearing on our bones.

We finally sounded like a band more than like a sketch of a band, and we

were amazingly tight. When we toured Europe and the UK, the press com-

mented on our Stax-Volt influences—and they were right. We were half art

band and half funky groove band, something that the US press didn’t really

pick up on until we mutated into a full-on art-funk revue a few years later.

But it was all there, right from the beginning, though the proportions were

completely different. Chris and Tina were a great rhythm section, and though Chris didn’t play fancy, he played solid. That gave us a firm foundation for all the angular shit that I was throwing around.

What does

being tight

mean? It’s hard to define now, in an age where instrumental performances and even vocals can be digitally quantified and made to

perfectly fit the beat. I realize now that it doesn’t actually mean that everyone plays exactly to the beat; it means that everyone plays together. Sometimes a band that has played together a lot will evolve to where they play some parts ahead of the beat and some slightly behind, and singers do the same thing.

A good singer will often use the “grid” of the rhythm as something to play

with—never landing exactly on a beat, but pushing and pulling around and

against it in ways that we read, when it’s well done, as being emotional. It turns out that not being perfectly aligned with a grid is okay; in fact, sometimes it feels better than a perfectly metric fixed-up version. When Willie

Nelson or George Jones sing way off the beat, it somehow increases the sense 44 | HOW MUSIC WORKS