How Music Works (4 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

to movie acting, the requirements of musical mediums are somewhat mutually

exclusive. What is best for one might work for the other, but it doesn’t always work that way.

Performers adapted to this new technology. The microphones that

recorded singers changed the way they sang and the way their instru-

ments were played.O Singers no longer had to have great lungs to be success-

ful. Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby were pioneers when it came to singing

“to the microphone.” They adjusted their vocal dynamics in ways that would

have been unheard of earlier. It might not seem that radical now, but croon-

ing was a new kind of singing back then. It wouldn’t have worked without

a microphone.

Chet Baker even sang in a whisper, as did João Gilberto, and millions fol-

lowed. To a listener, these guys are whispering like a lover, right into your ear, getting completely inside your head. Music had never been experienced that

way before. Needless to say, without microphones this intimacy wouldn’t

have been heard at all.

Technology had turned the living room or any small bar with a jukebox into

a concert hallP—and often there was dancing. Besides changing the acoustic

context, recorded music also allowed music venues to come into existence

without stages and often without any live musicians at all. DJs could play at high school dances, folks could shove quarters into jukeboxes and dance in

the middle of the bar, and in living rooms the music came out of furniture.

Eventually venues evolved that were purposefully built to play only this kind of performerless music—discos.Q

O

P

Music written for contemporary discos, in my opinion, usually

only

works in those social and physical spaces—it really works best on the incredible

sound systems that are often installed in those rooms. It feels stupid to

listen to club music at its intended volume at home, though people do it.

And, once again, it’s for dancing, as was early hip-hop, which emerged out

of dance clubs in the same way that jazz did—by extending sections of the

music so the dancers could show off and improvise. Once again the dancers

were changing the context, urging the music in new directions.R

In the sixties the most successful pop music began to be performed in

basketball arenas and stadiums, which tend to have terrible acoustics—

only a narrow range of music works at all in such environments. Steady-

state music (music with a consistent volume, more or less unchanging tex-

tures, and fairly simple pulsing rhythms) works best, and even then rarely.

The roar of metal works fine. Industrial music for industrial spaces. Stately chord progressions might survive, but funk, for example, bounced off the

walls and floors and became chaotic. The groove got killed, though some

funky acts persevered because these concerts were social gatherings, bond-

ing opportunities, and rituals as much as music events. Mostly the arenas

were filled with white kids—and the music was usually Wagnerian.

The gathered masses in sports arenas and stadiums demanded that the

music perform a different function—not only sonically but socially—than

what it had been asked to do on a record or in a club. The music those bands ended up writing in response—arena rock—is written with that in mind:

rousing, stately anthems. To my ears it’s a soundtrack for a gathering, and

Q

R

listening to it in other contexts recreates the memory or anticipation of that gathering—a stadium in your head.

CONTEMPORARY MUSIC VENUES

Where are the new music venues? Are there venues I’m still not acknowl-

edging that might be influencing how and what kind of music gets

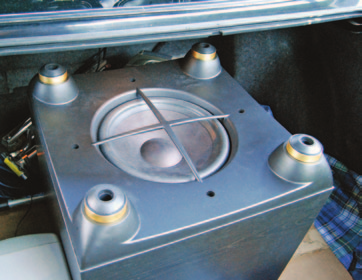

written? Well, there is the interior of your car.S I’d argue that contemporary hip-hop is written (or at least the music is) to be heard in cars with systems like the one below. The massive volume seems to be more about sharing your

music with everyone, gratis!T In a sense, it’s a music of generosity. I’d say the audio space in a car with these speakers forces a very different kind of composition. The music is bass heavy, but with a strong and precise high end as well. Sonically, what’s in the middle? It’s the vocal, allocated a vacant sonic space where not much else lives. In earlier pop music, the keyboards or guitars or even violins often occupied much of this middle territory, and without those things, the vocals rushed to fill the vacuum.

Hip-hop is unlike anything one could produce with acoustic instruments.

That umbilical cord has been cut. Liberated. The connection between the recorded music and the live musician and performer is now a thing of the past. Although this music may have emerged from dance-oriented early hip-hop (which, like

jazz, evolved by extending the breaks for dancers), it’s morphed into something else entirely: music that sounds best in cars. People do dance in their cars, or they try to. As big SUVs become less practical I foresee this music changing as well.

S

T

One other new music venue has arrived.U Presumably the MP3 player

shown below plays mainly Christian music. Private listening really took off

in 1979, with the popularity of the Walkman portable cassette player. Lis-

tening to music on a Walkman is a variation of the “sitting very still in a

concert hall” experience (there are no acoustic distractions), combined with the virtual space (achieved by adding reverb and echo to the vocals and

instruments) that studio recording allows. With headphones on, you can

hear and appreciate extreme detail and subtlety, and the lack of uncontrol-

lable reverb inherent in hearing music in a live room means that rhythmic

material survives beautifully and completely intact; it doesn’t get blurred

or turned into sonic mush as it often does in a concert hall. You, and only

you, the audience of one, can hear a million tiny details, even with the compression that MP3 technology adds to recordings. You can hear the singer’s

breath intake, their fingers on a guitar string. That said, extreme and sudden dynamic changes can be painful on a personal music player. As with dance

music one hundred years ago, it’s better to write music that maintains a

relatively constant volume for this tiny venue. Dynamically static but with

lots of details: that’s the directive here.

If there has been a compositional response to MP3s and the era of private

listening, I have yet to hear it. One would expect music that is essentially a soothing flood of ambient moods as a way to relax and decompress, or

maybe dense and complex compositions that reward repeated playing and

attentive listening, maybe intimate or rudely erotic vocals that would be

inappropriate to blast in public but that you could enjoy privately. If any of this is happening, I am unaware of it.

We’ve come full circle in many ways. The musical techniques of the Afri-

can Diaspora, the foundation of much of the contemporary world’s popular

music, with its wealth of interlocking and layered beats, works well acous-

tically in both the context of the

private listening experience and as

a framework for much contempo-

U

rary recorded music. African music

sounds the way it does because it

was meant to be played out in the

open (a form of steady-state music

loud enough to be heard outdoors

DAV I D BY R N E | 27

above dancing and singing) but it turns out to also work well in the most

intimate of spaces—our inner ears. Yes, people do listen to Bach and Wagner

on iPods, but not too many people are writing new music like that, except

for film scores, where Wagnerian bombast works really well. If John Williams wrote contemporary Wagner for

Star Wars

, then Bernard Herrmann wrote contemporary Schoenberg for

Psycho

and other Hitchcock movies. The symphony hall is now a movie theater for the ears.