How Music Works (3 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

the dancing, clomping feet, and gossiping, one might have had to figure out

how to make the music louder, and the only way to do this was to increase the size of the orchestra, which is what happened.

Meanwhile, some folks around that same time were going to hear operas.

La Scala was built in 1776; the original orchestra section comprised a series of booths or stalls, rather than the rows of seats that exist now.J People would eat, drink, talk, and socialize during the performances—audience behavior, a big part of music’s context, was very different back then. Back in the day, people would socialize and holler out to one another during the performances.

They’d holler at the stage, too, for encores of the popular arias. If they liked a tune, they wanted to hear it again—now! The vibe was more like CBGB than

your typical contemporary opera house.

La Scala and other opera venues of the time were also fairly compact—

more so than the big opera houses that now dominate much of Europe and

the United States. The depth of La Scala and many other opera houses of that period is maybe like the Highline Ballroom or Irving Plaza in New York, but

La Scala is taller, with a larger stage. The sound in these opera houses is pretty tight, too (unlike today’s larger halls). I’ve performed in some of these old opera venues, and if you don’t crank the volume too high, it works surprisingly well for certain kinds of contemporary pop music.

Take a look at Bayreuth, the opera house Wagner had built for his own

music in the 1870s.K You can see it’s not that huge. Not very much bigger

than La Scala. Wagner had the gumption to demand that this venue be built

to better accommodate the music he imagined—which didn’t mean there

J

K

was much more seating, as a practical-minded entrepeneur might insist on

today. It was the orchestral accommodations themselves that were enlarged.

He needed larger orchestras to conjure the requisite bombast. He had new and larger brass instruments created too, and he also called for a larger bass section, to create big orchestral effects.

Wagner in some ways doesn’t fit my model—his imagination and ego

seemed to be larger than the existing venues, so he was the exception who

didn’t accommodate. Granted, he was mainly pushing the boundaries of pre-

existing opera architecture, not inventing something from scratch. Once he

built this place, he more or less wrote for it and its particular acoustic qualities.

As time passed, symphonic music came to be performed in larger and

larger halls. That musical format, originally conceived for rooms in palaces and the more modest-sized opera halls, was now somewhat unfairly being

asked to accommodate more reverberant spaces. Subsequent classical com-

posers therefore wrote music for those new halls, with their new sound,

and it was music that emphasized texture, and sometimes employed audio

shock and awe in order to reach the back row that was now farther away. They needed to adapt, and adapt they did.

The music of Mahler and other later symphonic composers works well in

spaces like Carnegie Hall.L Groove music, percussive music featuring drums—

like what I do, for example—has a very hard time here. I’ve played at Carnegie Hall a couple of times, and it can work, but it is far from ideal. I wouldn’t play that music there again. I realized that sometimes the most prestigious place doesn’t always work out best for your music. This acoustic barrier could be

L

M

viewed as a subtle conspiracy, a sonic wall, a way of keeping the riffraff out—

but we won’t go there, not yet.

POPULAR MUSIC

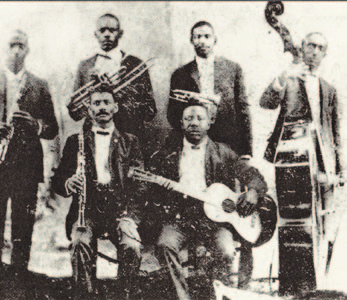

At the same time that classical music was tucking itself into new venues,

so too was popular music. In the early part of the last century, jazz devel-

oped alongside later classical music. This popular music was originally played in bars, at funerals, and in whorehouses and joints where dancing was going

on. There was little reverberation in those spaces, and they weren’t that big, so, as in CBGB, the groove could be strong and up front.M

It’s been pointed out by Scott Joplin and others that the origin of jazz solos and improvisations was a pragmatic way of solving a problem that had emerged: the “written” melody would run out while the musicians were playing, and in

order to keep a popular section continuing longer for the dancers who wanted to keep moving, the players would jam over those chord changes while maintaining the same groove. The musicians learned to stretch out and extend whatever section of the tune was deemed popular. These improvisations and elongations evolved out of necessity, and a new kind of music came into being.

By the mid-twentieth century, jazz had evolved into a kind of classical

music, often presented in concert halls, but if anyone’s been to a juke joint or seen the Rebirth or Dirty Dozen brass bands at a place like the Glass

House in New Orleans, then you’ve seen lots of dancing to jazz. Its roots

are spiritual dance music. Yes, this is one kind of spiritual music that would sound terrible in most cathedrals.

The instrumentation of jazz was also modified so that the music could be

heard over the sound of the dancers and the bar racket. Banjos were louder

than acoustic guitars, and trumpets were nice and loud, too. Until amplification and microphones came into common use, the instruments written for

and played were adapted to fit the situation. The makeup of the bands, as well as the parts the composers wrote, evolved to be heard.

Likewise, country music, blues, Latin music, and rock and roll were all

(originally) music to dance to, and they too had to be loud enough to be heard above the chatter. Recorded music and amplification changed all that, but

when these forms jelled, such factors were just beginning to be felt.

DAV I D BY R N E | 21

QUIET, PLEASE

With classical music, not only did the venues change, but the behavior

of the audiences did, too. Around 1900, according to music writer

Alex Ross, classical audiences were no longer allowed to shout, eat, and chat during a performance. One was expected to sit immobile and listen with rapt

attention. Ross hints that this was a way of keeping the hoi polloi out of the new symphony halls and opera houses.2 (I guess it was assumed that the lower classes were inherently noisy.) Music that in many instances used to be for

all was now exclusively for the elite. Nowadays, if someone’s phone rings or a person so much as whispers to their neighbor during a classical concert, it could stop the whole show.

This exclusionary policy affected the music being written, too—since no

one was talking, eating, or dancing anymore, the music could have extreme

dynamics. Composers knew that every detail would be heard, so very quiet

passages could now be written. Harmonically complex passages could be

appreciated as well. Much of twentieth-century classical music could only

work in (and was written for) these socially and acoustically restrictive spaces.

A new kind of music came into existence that didn’t exist previously—and

the future emergence and refining of recording technology would make this

music more available and ubiquitous. I do wonder how much of the audience’s

fun was sacrificed in the effort to redefine the social parameters of the concert hall—it sounds almost masochistic of the upper crust, curtailing their own

liveliness, but I guess they had their priorities.

Although the quietest harmonic and dynamic details and complexities

could now be heard, performing in these larger more reverberant halls meant

that rhythmically things got less distinct and much fuzzier—less African, one might say. Even the jazz now played in these rooms became a kind of chamber

music. Certainly no one danced, drank, or hollered out “Hell, yeah!” even if it was Goodman, Ellington, or Marsalis playing—bands that certainly swing.

The smaller jazz clubs followed suit; no one dances anymore at the Blue Note or Village Vanguard, though liquor is very quietly served.

One might conclude that removing the funky relaxed vibe from refined

American concert music was not accidental. Separating the body from the head seems to have been an intended consequence—for anything to be serious, you

couldn’t be seen shimmying around to it. (Not that any kind of music is aimed 22 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

exclusively at either the body or head—that absolute demarcation is somewhat of an intellectual and social construct.) Serious music, in this way of thinking, is only absorbed and consumed above the neck. The regions below the neck

are socially and morally suspect. The people who felt this way and enforced

this way of encountering music probably didn’t take the wildly innovative and sophisticated arrangements of mid-century tango orchestras seriously either.

The fact that it was wildly innovative and at the same time very danceable created, for twentieth-century sophisticates, a kind of cognitive dissonance.

RECORDED MUSIC

With the advent of recorded music in 1878, the nature of the places in

which music was heard changed. Music now had to serve two very

different needs simultaneously. The phonograph box in the parlor became a

new venue; for many people, it replaced the concert hall or the club.

By the thirties, most people were listening to music either on radio or on

home phonographs.N People probably heard a greater quantity of music, and a

greater variety, on these devices than they would ever hear in person in their lifetimes. Music could now be completely free from any live context, or, more properly, the context in which it was heard became the living room and the

jukebox—parallel alternatives to still-popular ballrooms and concert halls.

The performing musician was now expected to write and create for two

very different spaces: the live venue, and the device that could play a recording or receive a transmission. Socially and acoustically, these spaces were worlds apart. But the compositions were expected to be the same! An audience who

heard and loved a song on the radio naturally wanted to hear that same song at the club or the concert hall.

These two demands seem unfair

N

to me. The performing skills, not

to mention the writing needs, the

instrumentation, and the acous-

tic properties for each venue are

completely different. Just as stage

actors often seem too loud and

demonstrative for audiences used

DAV I D BY R N E | 23