How Music Works (36 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

sublime, and they made it come alive for me. Having visited Manila, I could

DAV I D BY R N E | 197

picture the neighborhoods, the houses and streets these people described,

the way their daily lives intersected with historical events. People tended

to mention very specific details that swirled around and were folded into

the onward rush of history. Joggers out for a morning run as tanks appeared

on the streets. Going out for coffee to find hundreds of thousands gathered

around the corner from your home.

Coincidentally, at this time I was also reading a book by Rebecca Solnit

called

A Paradise Built in Hell

, about the almost utopian social transformations that sometimes emerge out of disasters and revolutions—citizens

spontaneously and selflessly helping one another after traumatic events

such as the San Francisco and Mexico earthquakes, the London blitz, and

the 9/11 attacks. All these events have in common a magical and all too

brief moment when class and other social differences vanish, and a common

humanity becomes evident. These moments often last only a few days, but

they have a profound and lasting impact on the participants, who witness a

door cracked open a little to reveal a better world, one whose existence they never forget.

The Filipino People Power Revolution looked to me like one of those

moments, and I hoped that a tiny bit of that feeling could be captured in

songs and scenes. A theatrical piece that had previously struck me as a tragedy might also have a kind of happy and even inspirational ending, not simply by describing the overthrow of one dictator and his wife, but because the

humanity of a people might allow itself to be revealed.

I’m not sure

Here Lies Love

will be a successful theater piece—creatively or commercially—but being able to write songs in which I function as the conduit for the feelings and thoughts of others was hugely liberating and, well, easier than I thought. It’s writing to order, but without too much vagueness in the intention, as the sources—the people—are as real as what happened.

EMERGENT STORYTELLING

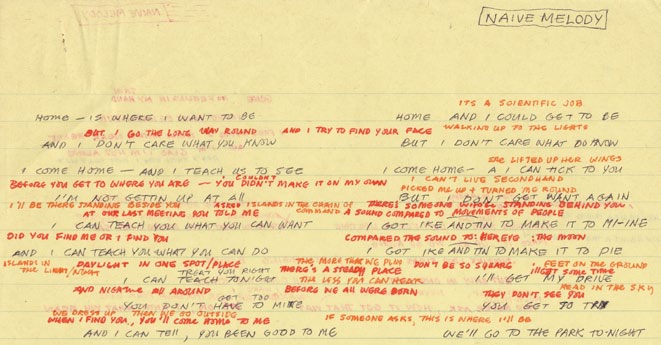

Writing words to fit an existing melody and meter, as I did on

Every-

thing That Happens

and many other records, is something anyone

who writes in rhyme does naturally and intuitively—every rapper impro-

vises or composes to a meter, for example. I had been encouraged to make

198 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

this process, which is usually internalized, more explicit when I was writ-

ing the words for

Remain in Light

. That was the first time I tackled a whole record of lyrics this way. I found that, remarkably, solving the puzzle of

making words and phrases fit existing structures often resulted, somewhat

surprisingly, in words that have an emotional consistency and sometimes

even a narrative thread, even though those aspects of the texts weren’t

planned ahead of time.

How does this happen? With

Remain in Light

and even before that, I would look for words that fit pre-existing melodic fragments that I or others had

come up with. After filling lots of pages with non-sequitors, I would scan

them to see if a lyrically resonant group emerged. Phrases that would hint at the beginning of an actual subject often seemed to

want

to emerge. This might seem magical—claiming that a text “wants” to come into being (and we’ve

heard this said before), but it’s true. When some phrases, even if collected almost at random, begin to resonate together and appear to be talking about

the same thing, it’s tempting to claim they have a life of their own. The lyrics may have begun as gibberish, but often, though not always, a “story” in the

broadest sense emerges. Emergent storytelling, one might say.

But at times words can be a dangerous addition to music—they can pin it

down. Words imply that the music is about what the words say, literally, and nothing more. If done poorly, they can destroy the pleasant ambiguity that constitutes much of the reason we love music. That ambiguity allows listeners to psychologically tailor a song to suit their needs, sensibilities, and situations, but words can limit that, too. There are plenty of beautiful pieces of music that I can’t listen to because they’ve been “ruined” by bad words—my own and others. In Beyoncé’s song “Irreplaceable,

”

she rhymes “minute” with “minute,” and I cringe every time I hear it (partly because by that point I’m singing along). On my own song “Astronaut,” I wrap up with the line “feel like I’m an astronaut,”

which seems like the dumbest metaphor for alienation ever. Ugh.

So I begin by improvising a melody over the music. I do this by singing

nonsense syllables, but with weirdly inappropriate passion, given that I’m not saying anything. Once I have a wordless melody and a vocal arrangement that

my collaborators (if there are any) and I like, I’ll begin to transcribe that gibberish as if it were real words.

I’ll listen carefully to the meaningless vowels and consonants on the recording, and I’ll try to understand what that guy (me), emoting so forcefully but DAV I D BY R N E | 199

inscrutibly, is actually saying. It’s like a forensic exercise. I’ll follow the sound of the nonsense syllables as closely as possible. If a melodic phrase of gibberish ends on a high

ooh

sound, then I’ll transcribe that, and in selecting actual words, I’ll try to choose one that ends in that syllable, or as close to it as I can get. So the transcription process often ends with a page of real words, still fairly random, that sound just like the gibberish.

I do that because the difference between an

ohh

and an

aah

, and a B and a TH sound is, I assume, integral to the emotion that the story wants to express.

I want to stay true to that unconscious, inarticulate intention. Admittedly

that content has no narrative, or might make no literal sense yet, but it’s in there—I can hear it. I can feel it. My job at this stage is to find words that acknowledge and adhere to the sonic and emotional qualities rather than to

ignore and possibly destroy them.

Part of what makes words work in a song is how they sound to the ear and

feel on the tongue. If they feel right physiologically, if the tongue of the singer and the mirror neurons of the listener resonate with the delicious appropriateness of the words coming out, then that will inevitably trump literal

sense, although literal sense doesn’t hurt. If recent neurological hypotheses regarding mirror neurons are correct, then one could say that we empatheti-cally “sing”—with both our minds and the neurons that trigger our vocal and

diaphragm muscles—when we hear and see someone else singing. In this

sense, watching a performance and listening to music is

always

a participatory activity. The act of putting words down on paper is certainly part of songwriting, but the proof is in seeing how it

feels

when it’s sung. If the sound is untrue, the listener can tell.

I try not to pre-judge anything that occurs to me at this point in the writ-

ing process—I never know if something that sounds stupid at first will in

some soon-to-emerge lyrical context make the whole thing shine. So no mat-

ter how many pages get filled up, I try to turn off the internal censor.D

Sometimes sitting at a desk trying to force this doesn’t work. I never

have writer’s block, exactly, but sometimes things do slow down. At those

times I ask myself if my conscious mind might be thinking too much—and

it is exactly at this point that I most want and need surprises and weird-

ness from the depths. Some techniques help in that regard. For instance, I’ll carry a micro-recorder and go jogging on the West Side, recording phrases

that match the song’s meter as they occur to me. On the rare occasion that

200 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

I’m driving a car, I can do the same thing (are there laws against driving and songwriting?). Basically, anything—driving, jogging, swimming, cooking,

cycling—that occupies part of the conscious mind and distracts it, works.

The idea is to allow the chthonic material the freedom it needs to gurgle

up. To distract the gatekeepers. Sometimes just a verse, or even a phrase or two, will resonate and be sufficient, and that’s enough to “unlock” the whole thing. From there on, it becomes more like fill-in-the-blank, conventional

puzzle solving.

This particular writing process could also be viewed as a collaboration: a

collaboration with oneself, with one’s subconscious as well as with the col-

lective unconscious, as Jung would put it. As in dreams, it often seems as

if a hidden part of oneself, a doppelgänger, is attempting to communicate,

to impart some important information. When we write, we access different

aspects of ourselves, different characters, different parts of our brains and hearts. And then, when they’ve each had their say, we mentally switch hats,

step back from accessing our myriad selves, and take a more distanced and

critical view of what we’ve done. Don’t we always work by editing and struc-

turing the outpouring of our many selves? Isn’t the end product the result of two or more sides of ourselves working with one another? We’ve often heard

this process described by creative folks as “channeling,” or just as often people

D

refer to themselves as a conduit for some force that speaks through them. I

suspect that the outside entity—the god, the alien, the source—is a part of

oneself, and that this kind of creation is about learning how to listen to and collaborate with it.

c h a p t e r s e v e n

Business and

Finances

Distribution & Survival Options for Musical Artists

202 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

c h a p t e r s e v e n

Business and

Finances

Distribution & Survival Options for Musical Artists

After the studio work is finished, after the record has been mixed

and pressed, how does a song or album get from the composer

or the performer to the listener?

How important is that? How important is getting one’s

work out to the public? Should that even really matter to

a creative artist? Would I make music if no one were listening? If I were a

hermit and lived on a mountaintop like a bearded guy in a cartoon, would I

take the time to write a song? Many visual artists whose work I love—like

Henry Darger, Gordon Carter, and James Castle—never shared their art. They

worked ceaselessly and hoarded their creations, which were discovered only

after they died or moved out of their apartments. Could I do that? Why would I? Don’t we want some validation, respect, feedback? Come to think of it, I

might do it—in fact, I did, when I was in high school puttering around with

those tape loops and splicing. I think those experiments were witnessed by

exactly one friend. However, even an audience of one is not zero.

Still, making music is its own reward. It feels good and can be a thera-

peutic outlet; maybe that’s why so many people work hard in music for

no money or public recognition at all. In Ireland and elsewhere, amateurs

play well-known songs in pubs, and their ambition doesn’t stretch beyond

the door. They are getting recognition (or humiliation) within their village, DAV I D BY R N E | 203

though. In North America, families used to gather around the piano in the

parlor. Any monetary remuneration that might have accrued from these

“concerts” was secondary. To be honest, even tooling around with tapes

in high school, I think I imagined that someone, somehow, might hear my

music one day. Maybe not those particular experiments, but I imagined that

they might be the baby steps that would allow my more mature expressions

to come into being and eventually reach others. Could I have unconsciously

had such a long-range plan? I have continued to make plenty of music, often

with no clear goal in sight, but I guess somewhere in the back of my mind I

believe that the aimless wandering down a meandering path will surely lead

to some (well-deserved, in my mind) reward down the road. There’s a kind

of unjustified faith involved here.

Is the satisfaction that comes from public recognition—however small,

however fleeting—a driving force for the creative act? I am going to assume

that most of us who make music (or pursue other creative endeavors) do

indeed dream that someday someone else will hear, see, or read what we’ve

made. Though Darger and some others might seem to be the exceptions, even