How Music Works (56 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

to question God’s plan and wisdom was heresy.

Murch theorized that the explanation might lie

in the fact that Copernicus knew about a Greek

astronomer named Aristarchos of Samos (c.

310–c.230 BCE), who had proposed his own sun-

centric system. Aristarchos even suggested that

the moon revolved around the Earth, but by Coper-

nicus’s time, his theories had been forgotten.

Here is Murch’s theory of how Copernicus

revived Aristarchos’s idea. Copernicus visited

Rome after completing his studies, where he

F

surely went to see the dome of the Pantheon,

G

which was one of the wonders of the age.G Murch

suggests that upon viewing that ceiling, Coper-

nicus put two and two together and sensed that

here, in this architecture, was encoded the secret

order of the solar system. This sounds very

Da

Vinci Code

, but read on.

To the right, Copernicus’s sun-centric system.H

Below it is a superimposition that Murch did,

H

placing Copernicus’s solar system over the con-

centric circles of the Pantheon’s dome.I

In the sun-centric system, the ratios (the dis-

tances between the planetary orbits) are still not

absolutely “correct,” so we’re not in perfect celes-

tial harmony just yet.

In the 1760s, the director of the Berlin obser-

vatory, Johann Daniel Titius, published a paper

that contained what came to be known as Bode’s

Law. It proposed some mathematical formulas and

constants that, Titus claimed, not only described

where the orbits of the planets were relative to the

I

sun, but also predicted where new planets would be

found—and therefore where the next “harmony”

should be. Shades of the periodic table! One can

predict musical overtones in much the same way.

DAV I D BY R N E | 309

As you can see in the diagram below, it all worked fine until the discovery

of Neptune, which didn’t fit the pattern.J In 1846, Bode’s Law was therefore abruptly abandoned and thrown into the pile of discarded and lost science.

Murch said:

So it seemed more logical (to me) to abandon the Astronomical Unit and just

concentrate on the ratios. Once you do that, the formula gets much simpler: it doesn’t have to do two things at once. This new formula is not only simpler, but it’s also lost its “Earth-centricity.” Now you can apply it equally to other orbital systems—the miniature “solar systems” of the moons around Jupiter, Saturn,

Uranus, and Neptune, for instance—and you find the same set of ratios cropping up! Underlying all the orbits of these moons and planets, there is a pattern of ratios, like the musical ratios underlying a keyboard. Just as you are restricted to playing certain musical ratios on many instruments, so it seems to be with the arrangements of these moons. Some systems “play”—or

occupy

—certain orbits, while others are left blank. By

playing

different orbits these systems generate a variety of chords. Chords we recognize. If I wrote the simplified Bode formula down on a piece of paper and showed it to music theorists, they would ask: “Why

J

Jupiter

Saturn

Uranus

Neptune

Pluto

RED: Orbits predicted by Bode’s Law

BLACK: Actual average distances of planets

are you showing us the formula of the overtone series…?” In other words, Bode’s Law gives a series of orbital ratios, which are mathematically identical to the common intervals in musical theory. They’re primarily variations on what we call the 7th chord: C, E, G, B flat.4

You might say that the universe plays the blues.

We’ve come back around to Pythagoras and the other Music of the Spheres

and universal harmony proponents. Pythagoras’s computations were slightly

off and didn’t quite match true musical ratios. It was Galileo’s dad, Vincenzo Galilei, who figured out the formula that generates a musical scale as we know it. The Renaissance architect Leone Battista Alberti said:

[I am] every day more and more convinced of the truth of Pythagoras’s saying, that Nature is sure to act consistently… I conclude that the same numbers by means of which the agreement of sounds affect our ears with delight, are the very same which please our eyes and our minds. We shall therefore borrow all our rules for the finishing of our proportions from the musicians… and from those things wherein nature shows herself most excellent and complete.5

Alberti went on to develop the formula for perspective in painting—a way

of mathematically organizing our vision.

Andrea Palladio, another, and rather more famous Renaissance architect,

used these same ratios in the buildings that he built in the sixteenth century, which have been emulated all over the world as designed of harmonic visual

and spacial relationships that are pleasing to the eye. Jefferson’s Monticello, hundreds of museums and monuments all over the world—they all owe their

proportions to Palladio, and to the cosmic musical ratios that he and others believed gave structure to all things.

Vitruvius was a Roman engineer and writer (born 70 BCE) whose ideas

were revived during the Renaissance, particularly by Daniele Barbaro, who

was also Palladio’s patron. Vitruvius espoused the ideas of symetria (sym-

metric objective beauty) and eurythmia (which is more about arrangement,

and is subjective and experiential). It was to illustrate a reappraisal of Vitruvius’s book

On Architecture

that Michelangelo drew his famous Vitruvian man (as you can see on the following page, he was somewhat emasculated by

NASA) that elucidated the divine proportions of the human body.K

RED: Orbits predicted by Bode’s Law

BLACK: Actual average distances of planets

DAV I D BY R N E | 311

Barbaro wrote that what harmony is for the ear, beauty is for the eye,

and this was made explicit in Palladio’s work. In the Villa Malcontenta (who would give such a name to their house?), there is a room that he describes as the “most beautiful and proportionate,” which is musically a major sixth. This room can be subdivided into smaller rooms, which work out to be a fourth

and a major third.

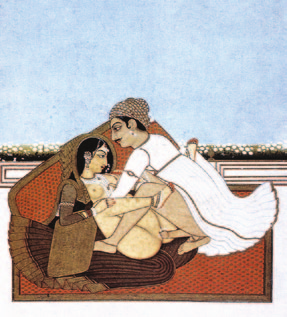

THE EAST

In the ancient Far East it was also thought that sound played an essen-

tial role in the formation of the universe. In Tantric Buddhism there is a

“sonoriferous” ether called the

akasha

, and from that ether flows the primor-dial vibrations. The

akasha

is self-generative—it didn’t come from something else, it made itself. But according to Tantric philosophy, this cosmic sound, which is sometimes referred to as Nãda-Brahman, actually comes from the

vibrations that emanate when Shiva and Shakti have sex.L

It is referred to as the Cosmic Orgasm, and from it the entire material uni-

verse was formed. A little more than a hundred years ago, Madame Blavatsky,

who developed a mystical system called Theosophy that was for a while

very popular, referred to this Nãda as the “soundless sound” or the “voice of silence.” Discreet, silent, true, esoteric, and momentous.

K

L

The idea that vibrations permeate everything is indisputable—you don’t

have to be a Tantric Buddhist or an Acousmatic to accept it. The Venn dia-

grams that contain spiritualist ideas, religious myths, and what we consider scientific fact do indeed overlap. Molecules vibrate at one hundred times per second, atoms faster than that. These vibrations produce what could be considered sound, albeit sound that we cannot hear. The composer John Cage said: Look at this ashtray. It’s in a state of vibration. We’re sure of that, and the physicist can prove it to us. But we can’t hear those vibrations… It would be extremely interesting to place it in a little anechoic chamber and listen to it through a suitable sound system. Object would become process; we would discover… the meaning of nature through the music of objects.6

None of these divine or ancient scientific theories really explains the

why

part—why we gravitate to the specific harmonies we do—unless you accept

“God made it that way, end of discussion” as an explanation. However, in our world of little faith, we ask for proof.

BIOLOGY AND THE NEUROLOGICAL BASIS FOR MUSIC

The question, then, is not only why do we like the harmonies we do, but

also does our enjoyment of music—our ability to find a sequence of

sounds emotionally affecting—have some neurological basis? From an evo-

lutionary standpoint, does enjoying music provide any advantage? Is music

of any truly practical use, or is it simply baggage that got carried along as we evolved other more obviously useful adaptations? Paleontologists Stephen

Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin wrote a paper in 1979 claiming that some

of our skills and abilities might be like spandrels—the architectural nega-

tive spaces above the curve of the arches of buildings—details that weren’t

originally designed as autonomous entities, but that came into being as a

result of other, more practical elements around them.

The linguist Noam Chomsky proposed that language itself might be an

evolutionary spandrel—that the ability to form sentences might not have

evolved directly but might be the byproduct of some other, more pragmatic

evolutionary development. In this view, many of the arts got a free ride along DAV I D BY R N E | 313

with the development of other, more prosaic qualities and cognitive abilities.

Dale Purves, a professor at Duke University, studied this question with his

colleagues David Schwartz and Catherine Howe, and they think they might

have some answers. First they describe the lay of the land: pretty much every culture uses notes selected from among the twelve that we typically use. From one A to another A an octave above it, there are usually twelve notes. This is not a scale, but there are twelve available notes, which on a piano would be all the black and white keys in one octave. (Scales are generally a smaller number of notes chosen from within those twelve.) There are billions of possible ways to divide the increments from A to A—yet twelve gives us a good start.