How to Live (15 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Throughout the troubled 1560s, Montaigne often went to Paris on

parlement

business, and apparently remained away through much of 1562 and early 1563, though he popped back to Bordeaux almost as readily as a modern car driver or train passenger might. He was certainly in the area in August 1563 when his friend Étienne de La Boétie died. And he must have been in Bordeaux in December 1563, for a strange incident occurred then, the most noteworthy of Montaigne’s few appearances in the city records.

The previous month, an extremist Catholic named François de Péruse d’Escars had launched a direct challenge to the

parlement’

s moderate president, Jacques-Benoît de Lagebâton, marching into the chambers and accusing him of having no right to govern.

Lagebâton successfully faced him down, but d’Escars challenged him again the following month, and in response Lagebâton produced a list of the court members he believed to be in cahoots with d’Escars, probably working for him for pay. Surprisingly, among these names appear those of Montaigne and of the recently deceased Étienne de La Boétie. One would have expected to find both firmly on Lagebâton’s side: La Boétie had been working actively for the chancellor L’Hôpital, of whom Lagebâton was a follower, and Montaigne too expressed admiration for that faction in his

Essays

. On the other hand, d’Escars was a family friend, and La Boétie had been at d’Escars’s home when he came down with the illness which would kill him. This was suspicious, and perhaps Montaigne came under scrutiny by association.

All the accused had a right to defend themselves before

parlement

—a chance for Montaigne to use his rhetorical skills again. Of them all, he was the speaker who made the biggest impression. “He expressed himself with all the vivacity of his character,” reads the note in the records. He finished his speech by stating “that he named the whole Court,” then he flounced off.

The court called him back and ordered him to explain what he meant by this. He replied that he was no enemy of Lagebâton, who was a friend of his and of everyone in his family. But—and there was clearly a “but” coming—he knew that accused persons were traditionally allowed to make counter-claims against their accuser, so he wished to take advantage of this right. Again, he left everyone puzzled, but the implication was that it was Lagebâton who was guilty of some impropriety. Montaigne made no further explanation. Pressed to withdraw the remark, he did, and there the matter ended. The accusations apparently came to nothing serious, and were quietly forgotten.

It remains an enigmatic incident, but it certainly shows us a different Montaigne from the cool, measured writer of the

Essays

, or his own portrait of his youthful self a-slumber over his books. This is a man known for “vivacity” and given to rushing in and out of rooms, making accusations which he cannot substantiate, and jabbering so wildly that no one is sure what he means to say. Montaigne does admit, in the

Essays

, that “by my nature I am subject to sudden outbursts which, though slight and brief, often harm my affairs.”

The last part of this makes one wonder if he damaged his career in

parlement

with his intemperate words, on other occasions if not on this one.

Even more surprising than meeting the hot-headed side of young Montaigne is seeing him bracketed with the bigots and extremists. His political allegiances were complicated; it is not always easy to guess where he will come out on any particular topic. But this case may have had more to do with personal loyalties than conviction. His own family had connections on both sides of the political divide, and he had to stay on good terms with them all. Perhaps the strain of this conflict made him volatile. The accusation was also an insult—to himself and, more seriously, to La Boétie, who was no longer around to offer any defense. Lagebâton was querying the honor of the most honorable man Montaigne had ever known:

the person he probably loved most in his entire life, and whom he had just lost. A response of helpless rage is understandable.

Slowness and forgetfulness were good responses to the question of how to live, so far as they went. They made for good camouflage, and they allowed room for thoughtful judgments to emerge. But some experiences in life brought forth a greater passion, and called for a different sort of answer.

LA BOÉTIE

:

LOVE AND TYRANNY

M

ONTAIGNE WAS IN

his mid-twenties when he met Étienne de La Boétie. Both were working at the Bordeaux

parlement

, and each had heard a lot about the other in advance. La Boétie would have known of Montaigne as an outspoken, precocious youngster. Montaigne had heard of La Boétie as the promising author of a controversial manuscript in local circulation, called

De la Servitude volontaire

(“On Voluntary Servitude”). He read this first in the late 1550s, and later wrote of his gratitude to it, because it brought him to its author. It started a great friendship: one “so entire and so perfect that certainly you will hardly read of the like … So many coincidences are needed to build up such a friendship that it is a lot if fortune can do it once in three centuries.”

Although the two young men were curious about each other, they somehow did not meet for a long time. In the end the encounter happened by chance. Both were at the same feast in the city; they got talking, and found themselves “so taken with each other, so well acquainted, so bound together” that, from that moment on, they became best friends. They had only six years, about a third of which was spent apart, since both were sometimes sent to work in other cities. Yet that short period bound them to each other as tightly as a lifetime of shared experience.

Reading about Montaigne and La Boétie, you often get the impression that the latter was much older and wiser than the former. In reality La Boétie was only a couple of years Montaigne’s senior. He was neither dashing nor handsome, but one has the impression that he was intelligent and warmhearted, with an air of substance. Unlike Montaigne, he was already married when they met, and he held a higher position in the

parlement

. Colleagues knew him both as a writer and as a public official, whereas Montaigne had yet to write anything except legal reports. La Boétie attracted attention and respect. If you were to tell their Bordeaux acquaintances of the early 1560s that he is

now remembered mainly for being Montaigne’s friend rather than the other way around, they would probably refuse to believe you.

Some of La Boétie’s air of maturity may have come from his having been orphaned at an early age. He was born on November 1, 1530, in the market town of Sarlat, about seventy-five miles from the Montaigne estate, in a fine, steep, richly ornamented building which survives today. This house had been built just five years earlier by La Boétie’s father, another hyperactive parent, who then died when his son was ten years old. His mother died, too, so La Boétie was left alone. An uncle who shared the name of Étienne de La Boétie took him in and apparently gave the boy a fashionable humanist education, though a less radical one than Montaigne’s.

Like Montaigne, La Boétie went on to study law. Some time around 1554, he married Marguerite de Carle, a widow who already had two children (one of whom would marry Montaigne’s younger brother Thomas de Beauregard). In May of the same year—two years before Montaigne started in Périgueux—La Boétie took up office at the Bordeaux

parlement

. He was probably one of those Bordeaux officials who looked askance at the better paid Périgueux men when they arrived.

La Boétie’s career in the Bordeaux

parlement

was a very good one. The strange accusations of 1563 aside, he was generally the kind of man who inspires confidence. He was given sensitive missions, and often entrusted with work as a negotiator—as Montaigne would later be. For the moment, La Boétie was probably thought the more reliable figure. He had the required air of gravity, and a better attitude to hard work and duty. The differences were significant, but the two men locked into each other like pieces in a puzzle. They shared important things: subtle thinking, a passion for literature and philosophy, and a determination to live a good life like the classical writers and military heroes they had grown up admiring. All this brought them together, and set them apart from their less adventurously educated colleagues.

La Boétie is now known mainly through Montaigne’s eyes—the Montaigne of the 1570s and 1580s, who looked back with sorrow and longing for his lost friend. This created a nostalgic fog through which one can only squint to try to make out the real La Boétie. Of Montaigne as seen by La Boétie, a clearer picture is available, for La Boétie wrote a sonnet

making it clear what he thought Montaigne needed by way of self-improvement. Instead of a perfect Montaigne frozen in memory, the sonnet captures a living Montaigne in the process of transition. It is by no means certain that this flawed character will ever make anything of himself, especially if he continues to waste his energies partying and flirting with pretty women.

Although La Boétie speaks to Montaigne like a fondly disapproving uncle, he adorns his poem with less familial emotions: “You have been bound to me, Montaigne, both by the power of nature and by virtue, which is the sweet allurement of love.”

Montaigne writes in the same way in the

Essays

, saying that the friendship seized his will and “led it to plunge and lose itself in his,” just as it seized the will of La Boétie and “led it to plunge and lose itself in mine.” Such talk was not unconventional.

The Renaissance was a period in which, while any hint of real homosexuality was regarded with horror, men routinely wrote to each other like lovestruck teenagers. They were usually in love less with each other than with an elevated ideal of friendship, absorbed from Greek and Latin literature. Such a bond between two well-born young men was the pinnacle of philosophy: they studied together, lived under each other’s gaze, and helped each other to perfect the art of living. Both Montaigne and La Boétie were fascinated by this model, and were probably on the lookout for it when they met. The shortness of their time together spared them disillusionment. In his sonnet, La Boétie expressed the hope that his and Montaigne’s names would be paired for all eternity, like those of other “famous friends” throughout history; he got his wish.

They seemed to think of their relationship above all by analogy with one particular classical model: that of the philosopher Socrates and his good-looking young friend Alcibiades—to whom La Boétie overtly compared Montaigne in his sonnet. Montaigne, in return, alluded to Socratic elements in La Boétie: his wisdom, but also a more surprising quality, his ugliness.

Socrates was famous for being physically unprepossessing, and Montaigne pointedly refers to La Boétie as having an “ugliness which clothed a very beautiful soul.” This echoes Alcibiades’ comparison, in Plato’s

Symposium

, of Socrates with the little “Silenus” figures popularly used as stash boxes for jewels and other precious items. Like Socrates, they sported grotesque faces

and figures on the outside but held treasures within. Montaigne and La Boétie apparently enjoyed these roles, and played them up for their amusement. At least it amused Montaigne. La Boétie’s sense of his own philosophical dignity would have prevented him from showing any sign if he felt insulted.

The ugly Socrates rejected the beautiful Alcibiades’s advances, according to Plato, yet their relationship was unmistakably flirtatious and sensual. Was the same true of Montaigne and La Boétie? Few today think that they had an outright sexual relationship, though the idea has had its followers. But the intensity of their language is striking, not just in La Boétie’s sonnet, but in the passages where Montaigne describes their friendship as a transcendent mystery, or as a great surge of love that swept them both away. His attachment to moderation in all things fails him when it comes to La Boétie, and so does his love of independence. He writes, “Our souls mingle and blend with each other so completely that they efface the seam that joined them, and cannot find it again.”

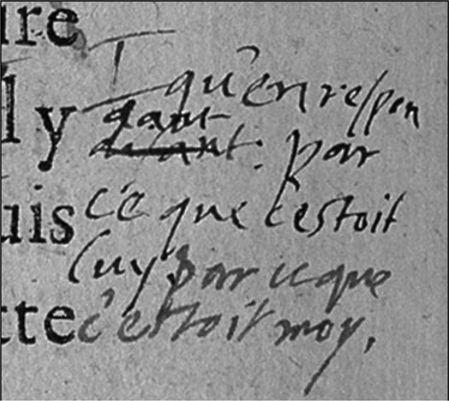

Words themselves refuse to do his bidding. As he wrote in a marginal addition:

If you press me to tell why I loved him, I feel that this cannot be expressed, except by answering: Because it was he, because it was I.

Renaissance friendships, like classical ones, were supposed to be chosen in the clear, rational light of day. That was why they were of philosophical value. Montaigne’s description of the love that “cannot be expressed” does not fit this pattern.

Indeed, he admits: “Our friendship has no other model than itself, and can be compared only with itself.” If it has a reference point at all, it again seems to be the

Symposium

, where Alcibiades finds himself equally confused by Socrates’s charisma, saying, “Many a time I should be glad for him to vanish from the face of the earth, but I know that, if that were to happen, my sorrow would far outweigh my relief. In fact, I simply do not know what to do about him.”