How to Live (36 page)

Authors: Sarah Bakewell

Another, less glamorous, reason for traveling existed too. From his father, Montaigne had inherited a propensity to attacks of kidney stones. Having seen Pierre literally pass out from the pain, he was more terrified of this illness than any other. Now, in his mid-forties, he found out for himself what this particular form of torture was like.

Kidney stones form when calcium or other minerals build up in the system and create lumps and crystals which block the flow of urine. They often splinter, creating jagged shards. Whole or split, they must pass through, and, as they do, they produce a sensation that feels like being sliced open from the inside. They also cause general discomfort around the kidneys, stabbing pains in the abdomen and back, and sometimes nausea and fever. Even once they are passed, that is not the end, for they often recur throughout life. In Montaigne’s day, they carried a real danger of death each time, either from simple blockage or from infection.

Today, stones can be broken up using sound waves to make the passage easier, but in Montaigne’s time one could only hope that the spheres, spikes, needles and burrs would find their own way to the exit.

He would try to sluice them out by refraining from urinating for as long as he could, to build up pressure; this was painful and dangerous in itself, but sometimes it worked. He tried other remedies, though he usually distrusted all forms of medicine. Once, he took “Venetian turpentine, which they say comes from the mountains of Tyrol, two large doses done up in a wafer on a silver spoon, sprinkled with one or two drops of some good-tasting syrup.” The only effect was to make his urine smell like March violets. The blood of a billy-goat fed on special herbs and wine was supposed to be efficacious. Montaigne tried this, rearing the goat at his estate, but he abandoned the idea on noticing calculi very similar to his own in the goat’s organs after it was killed. He did not see how one faulty urinary system could cure another.

The most common remedy for kidney stones was the use of spa waters and thermal baths. Montaigne went along with this too; at least it was a natural method, unlikely to do harm. The spas were often set in attractive

environments, and the company was interesting. He tried a couple in France in the late 1570s; the illness returned after each visit, but he was willing to try more. This therefore became another reason to travel, for the resorts of Switzerland and Italy were famous.

It had the virtue of being the kind of reason he could easily quote to his wife and friends.

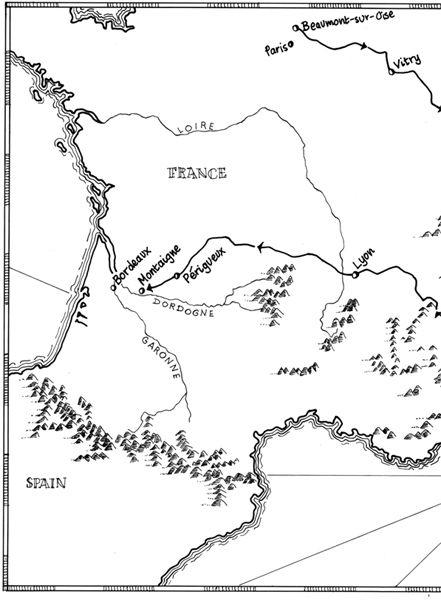

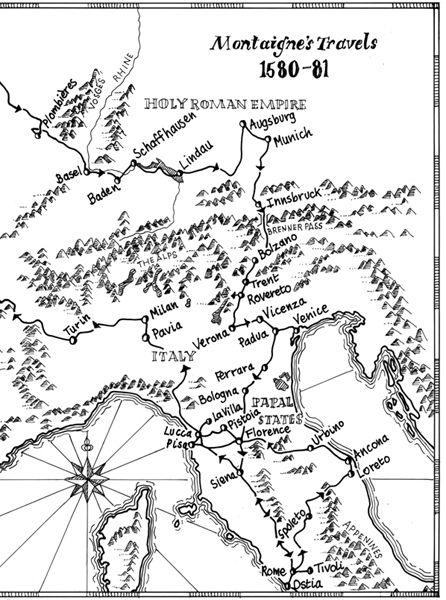

And so, in the summer of 1580, the renowned forty-seven-year-old author left his vines and set off to cure his ailment and see the world, or at least selected areas of the European world. The trip would keep him away until November 1581: seventeen months. He began with trips around parts of France, apparently on business and perhaps collecting instructions for political errands on the journey. It was now that he had his audience with Henri III, and presented him with his

Essays

. After this he turned east and crossed over into German lands, then towards the Alps and Switzerland, and finally to Italy. Had he had his way, the trip might have been longer and he might have ended up anywhere. At one point, he fancied going to

Poland. Instead, he contented himself with the more common goal of Rome—great pilgrimage site for every good Catholic and every Renaissance intellectual.

Montaigne did not have the luxury of traveling solo, following personal whim alone.

He was a nobleman of substance, and was expected to support an unwieldy entourage of servants, acquaintances, and hangers-on, from whom he tried to escape as often as possible. The group included four youngsters who came for the educational experience. One was his own youngest brother, Bertrand de Mattecoulon, still only twenty; the others were the young husband of one of his sisters and a neighbor’s teenage son with a friend.

As the voyage went on, each of these would peel away to take up various pursuits. The most ill-fated was Mattecoulon, who stayed in Rome to study fencing and there killed a man in a duel; Montaigne had to get him rescued from prison.

Traveling was itself something of an extreme sport at the time, not much less dangerous than dueling. Roads on established pilgrim routes could be good, but others were rough. You always had to be ready to change your plans on hearing reports of plague ahead, or of gangs of highwaymen.

Montaigne once altered his route to Rome because of a warning about armed robberies on the road he had intended to take.

Some people hired escorts, or traveled in convoy. Montaigne was already in a large group, which helped, but that could attract unwelcome attention too.

There were other irritations. Officials had to be bribed, especially in Italy, which was known for corruption and bureaucratic excess. Throughout Europe, the gates to cities were heavily guarded; you had to arrive with the correct passports, travel and baggage permits, plus properly attested letters stating that you had not recently been through a plague area. City checkpoints often issued a pass to stay at a particular hotel, the proprietor of which had to countersign it. It must have been like traveling in the Communist world at the height of the Cold War, but with greater lawlessness and danger.

Then there were the discomforts of the journey itself. Most traveling was done on horseback. You could go by carriage, but the seats were usually harder on the buttocks than saddles. Montaigne certainly preferred to ride. He would buy and sell horses on the way, or hire them for short stretches. River transport was another option, but Montaigne suffered from seasickness and avoided it. In general, riding gave him the freedom he craved; surprisingly, he also found a saddle the most comfortable place to be during a kidney-stone attack.

What he loved above all about his travels was the feeling of going with the flow.

He avoided all fixed plans. “If it looks ugly on the right, I take the left; if I find myself unfit to ride my horse, I stop.” He traveled as he read and wrote: by following the promptings of pleasure. Leonard Woolf, roaming Europe with his wife over three centuries later, would describe how she too cruised along like a whale sieving the ocean for plankton, cultivating a “passive alertness” which brought her a strange mingling of “exhilaration and relaxation.” Montaigne was the same. It was an extension of his everyday pleasure in letting himself “roll relaxedly with the rolling of the heavens,” as he luxuriously put it, but with the added delight that came from seeing everything afresh and with full attention, like a child.

He did not like to plan, but he did not like to miss things either. His secretary, accompanying him and (for a while) keeping his journal for him, remarked that people in the party complained about Montaigne’s habit of straying from the path whenever he heard of extra things he wanted to see. But Montaigne would say it was impossible to stray from the path: there

was

no path. The only plan he had ever committed himself to was that of traveling in unknown places.

So long as he did not repeat a route, he was following this plan to the letter.

The one limit to his energy was that he never liked to start out too early. “My laziness in getting up gives my attendants time to dine at their ease before starting.” This accorded with his usual habit, for he always had trouble getting under way in the mornings. On the whole, however, he made a point of shaking up his habits while traveling. Unlike other travelers, he ate only local food and had himself served in the local style.

At one point in the trip he regretted that he had not brought his cook with him—not because he missed home cooking, but because he wanted the cook to learn new foreign recipes.

He blushed to see other Frenchmen overcome with joy whenever they met a compatriot abroad. They would fall on each other, cluster in a raucous group, and pass whole evenings complaining about the barbarity of the locals. These were the few who actually noticed that locals did things differently. Others managed to travel so “covered and wrapped in a taciturn and incommunicative prudence, defending themselves from the contagion of an unknown atmosphere” that they noticed nothing at all. In the journal, the secretary observed how far Montaigne himself would err in the other direction, showering exaggerated praise on whichever country they were in while having nary a good word to say for his own. “In truth there entered into his judgment a bit of passion, a certain scorn for his country,” wrote the secretary, and added his own speculation that Montaigne’s aversion from all things French came from “other considerations”—perhaps a reference to the wars.

His adaptability extended to language. In Italy, he spoke in Italian and even kept his journal in that language, taking over from the secretary.

He imitated the chameleon, or octopus, and tried to pass incognito wherever possible—or what he thought was incognito. In Augsburg, wrote the secretary, “Monsieur de Montaigne, for some reason, wanted our party to dissemble and not tell their ranks; and he walked unattended all day long through the town.” It did not work. Sitting on a pew in freezing air in

Augsburg’s church, Montaigne found his nose running and unthinkingly took out a handkerchief. But handkerchiefs were not used in this area, so he blew his cover along with his nose. Was there a bad smell around? the local people wondered. Or was he afraid of catching something? In any case, they had already guessed he was a stranger: his style of dressing gave him away. Montaigne found this irksome. For once, “he had fallen into the fault that he most avoided, that of making himself noticeable by some mannerism at variance with the taste of those who saw him.”