How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare (26 page)

Read How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Online

Authors: Ken Ludwig

Tags: #Education, #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Arts & Humanities, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #General

FALSTAFF

(as Prince)

But to say I know more harm in him than in myself were to say more than I know. That he is old, the more the pity; his white hairs do witness it.… If sack and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked. If to be old and merry be a sin, then many an old host that I know is damned. If to be fat be to be hated, then Pharaoh’s lean kine are to be loved. No, my good lord, banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins, but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant being as he is old Jack Falstaff, banish not him thy Harry’s company, banish not him thy Harry’s company. Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world

.

PRINCE HAL

I do. I will

.

And now we see how the speech we’re memorizing fits into the puzzle. Falstaff delivers it in defense of himself, pretending that the lines are spoken by the Prince. This is Shakespeare’s genius at the height of its power.

You have already taught your children the first third:

If sack and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked. If to be old and merry be a sin, then many an old host that I know is damned. If to be fat be to be hated, then Pharaoh’s lean kine are to be loved

.

Now let’s teach them the rest of the speech:

No, my good lord

,

banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins

,

| Peto | P |

| Bardolph | B |

| Poins | P |

Peto, Bardolph, Poins

,

The names are wonderful because they sound nothing at all like names today. Peto. Bardolph. Poins. These rogues are now legendary.

but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff

,

And here’s another list:

sweet, kind, true, valiant

.

| sweet , | s |

| kind , | k |

| true , | t |

| valiant | v |

Lists like these can be tricky to memorize, so in our house we often use mnemonic devices to get us over the hump. For example, in my son’s music class at the time, some of the students played instruments, but seven kids took voice.

| S even | S weet |

| K ids | K ind |

| T ook | T rue |

| V oice | V aliant |

And the

o

in the word

voice

even helped us with the next adjective in the speech,

old

.

but for

sweet

Jack Falstaff

,

kind

Jack Falstaff

,

true

Jack Falstaff

,

valiant

Jack Falstaff

,

and therefore more valiant

being as he is

old

Jack Falstaff

,

The Subtlety of Falstaff

This last phrase epitomizes Falstaff’s extraordinary wit and intelligence:

and therefore more valiant being as he is old Jack Falstaff

,

It is not only logical and obviously true—that when you’re old, you have to be extra-valiant in order to be valiant at all—but it is also very touching: It appeals not only to the brain but also to the heart. One of the goals of this book is to introduce your children to the nuances of language, and this last phrase of the speech is a prime example.

and therefore more valiant

being as he is

old

Jack Falstaff

,

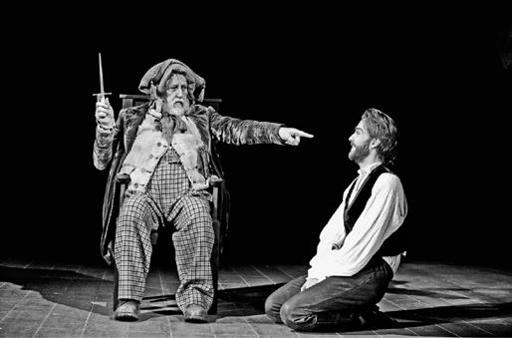

Henry IV, Part 1

at Theatre Royal Bath, with Desmond Barrit as Falstaff and Tom Mison as Prince Hal

(photo credit 24.2)

Peroration and Banishment

And now comes the inspiring conclusion to the speech:

banish not him thy Harry’s company

,

banish not him thy Harry’s company

.

Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world

.

Falstaff is the world, a very specific world. He is the world of truancy over duty, joy over tedium, passion over the ordinary, imagination over

littleness. He is dangerous, to be sure. He breaks laws. He steals from pilgrims. He is not a Santa Claus figure full of merry fun. Like all of Shakespeare’s greatest creations, he is a complex combination of moral traits, full of lights and darks.

For some Shakespeareans, Falstaff is darker than traditionally pictured. They remind us that he steals from his government and sends untested recruits off to war. He feigns death on the battlefield to save his skin, then claims heroism for further wounding a man who is dead. All the while, he proclaims (in a famous soliloquy) that notions of traditional honor have no place in his moral vocabulary. Yet Shakespeare obviously adores the old man. For Shakespeare, there is something deep within Falstaff to be admired. He represents everything in the world that is

not

buttoned-down,

not

rule-bound,

not

afraid of itself. Falstaff loves

being

Falstaff. He is full of life and wisdom, and he invents himself into something unforgettable.

As a young man, Benjamin Franklin frequently pushed a wagonload of paper around the streets of Philadelphia to show that he was an industrious printer. In fact, the paper had no destination; Franklin was doing it to create the illusion that he was industrious. Like all great men and women, he was inventing his own legend. Falstaff does the same thing right before our eyes: He invents the legend of Falstaff. And in the process, he talks better than any other character in English literature.

Repetition

Your children may ask: Why does Falstaff repeat the phrase

banish not him thy Harry’s company?

banish not him thy Harry’s company

,

banish not him thy Harry’s company

.

Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world

.

Could it have been a printing error? Yes, possibly. But I don’t think so. I think it’s a deliberate poetic choice on Shakespeare’s part to make the ending of the speech more moving; to give the actor playing Falstaff a

chance to make his plea twice, with a different reading each time; and to emphasize the importance of the banishment issue.

Abraham Lincoln and the Mangling of Shakespeare

The sixteenth president of the United States was a great lover of Shakespeare. He enjoyed reading the plays, and he saw them onstage as often as possible. But one of the things he could not understand was why the producers of his day cut out the Playacting Scene from

Henry IV, Part 1

.

Cut out?

From Shakespeare?

One thing that surprises most of us today is the extent to which directors and producers have changed Shakespeare’s texts over the past four hundred years. In Shakespeare productions these days, the director will commonly decide to make a few cuts. Shakespeare’s plays are long (a full-text

Hamlet

runs over four hours), and some sections are so confusing to us in the present day (like many of the jokes made by Shakespeare’s jesters) that small, judicious cuts can arguably be justified.

However, starting in the eighteenth century, many producers “improved” Shakespeare’s plays to accord with their own beliefs about what the plays “should” be saying and what they thought the public wanted. Thus, for many years,

King Lear

was performed with a happy ending tacked on—with Lear recovering, Cordelia getting married, and the three sisters happily reuniting. The greatest actor-producer of the eighteenth century, David Garrick, added fifty extra lines at the end of

Romeo and Juliet

so that the lovers could have a love scene together in the Capulets’ tomb before Romeo gasped his last.

The Winter’s Tale

was performed with only three of its five acts because the first two were considered “unnecessary.” And for much of the nineteenth century many people read a version of Shakespeare that was “bowdlerized” into

The Family Shakespeare

—that is, cut down by a brother and sister named Bowdler who took out every blasphemous and sexually suggestive word that a father, reading aloud to

his family, would consider embarrassing or improper. Today we consider such changes barbarous, but for more than a hundred years they were commonplace.

Thus, in Abraham Lincoln’s day, it was common to leave out the “play extempore” from Act II, Scene 4 of

Henry IV, Part 1

. In 1863 Lincoln saw such a production and invited the actor who played Falstaff, James Hackett, back to the White House after the performance. He wanted to know “why one of the best scenes in the play, that where Falstaff & Prince Hal alternately assume the character of the King, is omitted in the representation.” Lincoln’s secretary of state, John Hay, reported that “Hackett says it is admirable to read but ineffective on stage.” Lincoln, along with centuries of theatergoers, disagreed.

Passage 16

Falstaff’s Voice

Before I knew thee, Hal, I knew nothing, and now am I, if a man should speak truly, little better than one of the wicked

.

(

Henry IV, Part 1

, Act I, Scene 2, lines 99–101)

Why, Hal, ’tis my vocation, Hal. ’Tis no sin for a man to labor in his vocation

.

(

Henry IV, Part 1

, Act I, Scene 2, lines 110–11)

There lives not three good men unhanged in England, and one of them is fat and grows old

.

(

Henry IV, Part 1

, Act II, Scene 4, lines 133–35)

I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is in other men

.

(

Henry IV, Part 2

, Act I, Scene 2, lines 9–11)

We have heard the chimes at midnight, Master Shallow

.

(

Henry IV, Part 2

, Act III, Scene 2, lines 221–22)

T

here are many memorable aspects of

Henry IV, Part 1

: It has an exciting story about a rebellion, an extravagant set of characters, and a profound theme involving the struggle for the soul of the Prince of Wales. It has a strong political point of view and stirring battle scenes, and it’s very, very funny. But the most unforgettable part of the play is Falstaff, and his greatness lies in his distinctive voice. I want your children to recognize that voice, and I want them to use this chapter as a jumping-off point so that they learn to become acute to the

sounds

of Shakespeare.