How We Learn (14 page)

Authors: Benedict Carey

For lab researchers focused on improving retention, this finding should have rung a bell, and loudly. Recall, for a moment, Ballard’s “reminiscence” from

chapter 2

. The schoolchildren in his “Wreck of the Hesperus” experiment studied the poem only once but continued to improve on subsequent tests given days later, remembering more and more of the poem as time passed. Those intervals between

studying (memorizing) the poem and taking the tests—a day later, two days, a week—are exactly the ones that Spitzer found most helpful for retention. Between them, Gates and Spitzer had demonstrated that Ballard’s young students improved not by some miracle but because each test was an additional study session. Even then, after Spitzer published his findings in

The Journal of Educational Psychology

, the bell didn’t sound.

“We can only speculate as to why,” wrote Henry Roediger III and Jeffrey Karpicke, also then at Washington University, in a landmark 2006 review of the

testing effect, as they called it. One possible reason, they argued, is that psychologists were still primarily focused on the dynamics of forgetting: “For the purpose of measuring forgetting, repeated testing was deemed a confound, to be avoided.” It “contaminated” forgetting, in the words of one of Spitzer’s contemporaries.

Indeed it did, and does. And, as it happens, that contamination induces improvements in thinking and performance that no one predicted at the time. More than thirty years passed before someone picked up the ball again, finally seeing the possibilities of what Gates and Spitzer had found.

That piece of foolscap Winston Churchill turned in, with the smudges and blots? It was far from a failure, scientists now know—even if he scored a flat zero.

• • •

Let’s take a breather from this academic parsing of ideas and do a simple experiment, shall we? Something light, something that gets this point across without feeling like homework. I’ve chosen two short passages from one author for your reading pleasure—and pleasure it should be, because they’re from, in my estimation, one of the most savage humorists who ever strode the earth, however unsteadily. Brian O’Nolan, late of Dublin, was a longtime civil servant, crank, and pub-crawler who between 1930 and 1960 wrote novels, plays,

and a much beloved satirical column for

The Irish Times

. Now, your assignment: Read the two selections below, four or five times. Spend five minutes on each, then put them aside and carry on with your chores and shirking of same. Both come from a chapter called “Bores” in O’Nolan’s book

The Best of Myles:

Passage 1: The Man Who Can Pack

This monster watches you try to stuff the contents of two wardrobes into an attaché case. You succeed, of course, but have forgotten to put in your golf clubs. You curse grimly but your “friend” is delighted. He knew this would happen. He approaches, offers consolation and advises you to go downstairs and take things easy while he “puts things right.” Some days later, when you unpack your things in Glengariff, you find that he has not only got your golf clubs in but has included your bedroom carpet, the kit of the Gas Company man who has been working in your room, two ornamental vases and a card-table. Everything in view, in fact, except your razor. You have to wire 7 pounds to Cork to get a new leather bag (made of cardboard) to get all this junk home.

Passage 2: The Man Who Soles His Own Shoes

Quite innocently you complain about the quality of present-day footwear. You wryly exhibit a broken sole. “Must take them in tomorrow,” you say vaguely. The monster is flabbergasted at this passive attitude, has already forced you into an armchair, pulled your shoes off and vanished with them into the scullery. He is back in an incredibly short space of time and restored your property to you announcing that the shoes are now “as good as new.” You notice his own for the first time and instantly understand why his feet are deformed. You hobble home, apparently on stilts. Nailed to each shoe is an inch-thick slab of “leather” made from Shellac, saw-dust and cement.

Got all that? It’s not

The Faerie Queene

, but it’ll suffice for our purposes. Later in the day—an hour from now, if you’re going with the program—

re

study Passage 1. Sit down for five minutes and reread it a few more times, as if preparing to recite it from memory (which you are). When the five minutes are up, take a break, have a snack, and come back to Passage 2. This time, instead of restudying, test yourself on it. Without looking, write down as much of it as you can remember. If it’s ten words, great. Three sentences? Even better. Then put it away without looking at it again.

The next day, test yourself on both passages. Give yourself, say, five minutes on each to recall as much as you can.

So: Which was better?

Eyeball the results, counting the words and phrases you remembered. Without being there to look over your shoulder and grade your work, I’m going to hazard a guess that you did markedly better on the second passage.

That is essentially the experimental protocol that a pair of psychologists—Karpicke, now at Purdue, and Roediger—have used in a series of studies over the past decade or so. They’ve used it repeatedly, with students of all ages, and across a broad spectrum of material—prose passages, word pairs, scientific subjects, medical topics. We’ll review one of their experiments, briefly, just to be clear about the impact of self-examination. In a 2006 study, Karpicke and Roediger recruited 120 undergraduates and had them study two science-related passages, one on the sun and the

other on sea otters. They studied one of the two passages twice, in separate seven-minute sessions. They studied the other one once, for seven minutes, and in the next seven-minute session were instructed to write down as much of the passage as they could recall without looking. (That was the “test,” like we just did above with the O’Nolan passages.) Each student, then, had studied one passage two times—either the sea otters, or the sun—and the other just once, followed by a free recall test on it.

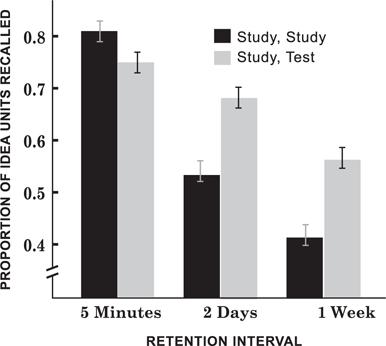

Karpicke and Roediger split the students into three groups, one of which took a test five minutes after the study sessions, one that got a test two days later, and one that tested a week later. The results are easily read off the following graph:

There are two key things to take away from this experiment. First, Karpicke and Roediger kept preparation time equal; the students got the same amount of time to try to learn both passages. Second, the “testing” prep

buried

the “study” prep when it really mattered, on the one-week test. In short, testing does not = studying, after all. In fact, testing > studying, and by a country mile, on delayed tests.

“Did we find something no one had ever found before? No, not really,” Roediger told me. Other psychologists, most notably Chizuko Izawa, had shown similar effects in the 1960s and ’70s at Stanford University. “People had noticed testing effects and gotten excited about them. But we did it with different material than before—the prose passages, in this case—and I think that’s what caught people’s attention. We showed that this could be applied to real classrooms,

and showed how strong it could be. That’s when the research started to take off.”

Roediger, who’s contributed an enormous body of work to learning science, both in experiments and theory, also happens to be one of the field’s working historians. In a review paper published in 2006, he and Karpicke analyzed a century’s worth of experiments, on all types of retention strategies (like spacing, repeated study, and context), and showed that the testing effect has been there all along, a strong, consistent “contaminant,”

slowing down forgetting. To measure any type of learning, after all, you have to administer a test. Yet if you’re using the test only for measurement, like some physical education push-up contest, you fail to see it as an added workout—itself making contestants’ memory muscles stronger.

The word “testing” is loaded, in ways that have nothing to do with learning science. Educators and experts have debated the value of standardized testing for decades, and reforms instituted by President George W. Bush in 2001—increasing the use of such exams—only inflamed the argument. Many teachers complain of having to “teach to the test,” limiting their ability to fully explore subjects with their students. Others attack such tests as incomplete measures of learning, blind to all varieties of creative thinking. This debate, though unrelated to work like Karpicke and Roediger’s, has effectively prevented their findings and those of others from being applied in classrooms as part of standard curricula. “When teachers hear the word ‘testing,’ because of all the negative connotations, all this baggage, they say, ‘We don’t need more tests, we need

less

,’ ” Robert Bjork, the UCLA psychologist, told me.

In part to soften this resistance, researchers have begun to call testing “retrieval practice.” That phrase is a good one for theoretical reasons, too. If self-examination is more effective than straight studying (once we’re familiar with the material), there must be reasons for it. One follows directly from the Bjorks’ desirable difficulty principle.

When the brain is retrieving studied text, names, formulas, skills, or anything else, it’s doing something different, and

harder

, than when it sees the information again, or restudies. That extra effort deepens the resulting storage and retrieval strength. We know the facts or skills better because we retrieved them ourselves, we didn’t merely review them.

Roediger goes further still. When we successfully retrieve a fact, he argues, we then restore it in memory in a different way than we did before. Not only has storage level spiked; the memory itself has new and different connections. It’s now linked to other related facts that we’ve also retrieved. The network of cells holding the memory has itself been altered. Using our memory changes our memory in ways we don’t anticipate.

And that’s where the research into testing takes an odd turn indeed.

• • •

What if you somehow got hold of the final exam for a course on Day 1, before you’d even studied a thing? Imagine it just appeared in your inbox, sent mistakenly by the teacher. Would having that test matter? Would it help you prepare for taking the final at the end of the course?

Of course it would. You’d read the questions carefully. You’d know what to pay attention to and what to study in your notes. Your ears would perk up anytime the teacher mentioned something relevant to a specific question. If you were thorough, you’d have memorized the correct answer to every item before the course ended. On the day of that final, you’d be the first to finish, sauntering out with an A+ in your pocket.

And you’d be cheating.

But what if, instead, you took a test on Day 1 that was comprehensive but

not

a replica of the final exam? You’d bomb the thing, to

be sure. You might not be able to understand a single question. And yet that experience, given what we’ve just learned about testing, might alter how you subsequently tune into the course itself during the rest of the term.

This is the idea behind

pretesting

, the latest permutation of the testing effect. In a series of experiments, psychologists like Roediger, Karpicke, the Bjorks, and Kornell have found that, in some circumstances, unsuccessful retrieval attempts—i.e., wrong answers—aren’t merely random failures. Rather, the attempts themselves alter how we think about, and store, the information contained in the questions. On some kinds of tests, particularly multiple-choice, we learn from answering incorrectly—especially when given the correct answer soon afterward.

That is,

guessing wrongly

increases a person’s likelihood of nailing that question, or a related one, on a later test.

That’s a sketchy-sounding proposition on its face, it’s true. Bombing tests on stuff you don’t know sounds more like a recipe for discouragement and failure than an effective learning strategy. The best way to appreciate this is to try it yourself. That means taking another test. It’ll be a short one, on something you don’t know well—in my case, let’s make it the capital cities of African nations. Choose any twelve and have a friend make up a simple multiple-choice quiz, with five possible answers for each nation. Give yourself ten seconds on each question; after each one, have your friend tell you the correct answer.

Ready? Put the smartphone down, close the computer, and give it a shot. Here are a few samples:

BOTSWANA:

• Gaborone

• Dar es Salaam

• Hargeisa

• Oran

• Zaria

(Friend: “Gaborone”)

GHANA:

• Huambo

• Benin

• Accra

• Maputo

• Kumasi

(Friend: “Accra”)

LESOTHO:

• Lusaka