Hugo! (33 page)

Authors: Bart Jones

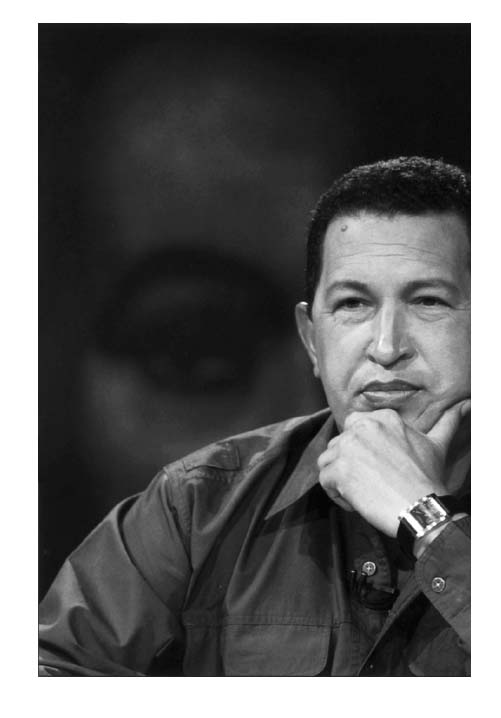

Simon Bolívar was never far from Chávez's

thoughts. During a

Hello, President

broadcast

in 2003, a portrait of the Liberator gazed down

on the man who hoped to fulfill his dream of a

united and more just Latin America. (Agencia

Bolivariana de Noticias)

Beauty and the Beast

A former Miss Universe, Irene Sáez was the mayor of the glitzy Chacao

section of Caracas. In a nation that worshipped beauty queens, Sáez

was the most popular politician in the land, according to the polls.

A six-foot-one strawberry blonde who referred to herself as a political

"atomic bomb," she was sweeping the imagination of the public, the

media, and the establishment with her clean-government agenda in

Chacao and the good looks and manners she'd learned to cultivate as

Miss Venezuela. It was a combination that seemed hard to beat.

In Venezuela beauty pageants were a religion. On the night of the

Miss Venezuela contest, the country came to a halt, with millions of

people glued to their television sets. The four-hour extravaganza was

the highest-rated show of the year, attracting at least two-thirds of the

viewing audience. It was the same routine the night of Miss Universe if

Venezuela's representative was in the running. She almost always was.

By the time Sáez rose to prominence in the political arena, Venezuela

was the undisputed beauty-queen capital of the world. Between 1979

and 1997 its women won ten major international titles. That was more

than any other country, even though Venezuela accounted for just 0.4

percent of the world population.

To some people Venezuela's obsession with beauty and beauty

pageants was a troubling sign of superficiality, of a tendency "to settle

for appearance rather than substance, and to avoid serious thinking."

Clearly, it was a nation virtually untouched by feminism. With an

average tropical temperature of eighty-two degrees in Caracas, and

even hotter in the interior, women dressed scantily to display their

charms. Skintight pants, blouses with plunging necklines, and open-back

or short dresses were standard attire for everyone from secretaries

to lawyers. It created a "strange city, with an aura of sexuality bordering

on the absurd." Men were free to voice their admiration; they were

almost expected to.

A national institution almost off limits to criticism, the Miss Venezuela

pageant produced a string of successful actresses and prosperous business

women. Irene Sáez chose a different route: politics. When she first

ran for office in 1992, most people thought it was a joke. She was a

mindless Miss. Or so they believed.

The youngest of six children of businessman Carlos Sáez and his

wife, Ligia, Irene was three years old when her mother succumbed to

cancer. Her death at forty devastated Irene and left a lasting mark. "I

used to look at the night sky and see my mother as the brightest star.

Since then, she's my guardian angel, my inner voice," Sáez told

People

magazine in a glowing portrait titled "Not Just Another Pretty Face."

After her mother's death, two older sisters helped raise her in a well-off,

conservative household. By the time she was nineteen and a university

engineering student, Irene's inner voice spoke to her. It told her to

compete for Miss Venezuela. Though she'd never had much interest in

pageants before, she entered at the last minute, just two weeks before it

took place.

With no dieting, no plastic surgery, no modeling experience, and

little preparation, Irene won. Shortly after she went on to take the Miss

Universe title. "I just knew in my heart and soul that I'd win," she told

People.

"I only wish that my mother had been with me to share the

moment." She spent a year traveling the world, meeting everyone from

Ronald Reagan to

Margaret Thatcher to Augusto Pinochet. After her

reign ended, she reportedly gave up a multimillion-dollar contract to

star opposite John Travolta in a movie. Hollywood, she said, "didn't

attract me."

Instead, she switched majors and took up political science at the

Central University of Venezuela, one of the country's top public universities.

She went on to serve for a year as Venezuela's cultural representative

to the United Nations. Sáez cultivated a reputation as a

devout Catholic who attended Mass almost every day, opposed abortion,

and volunteered in a church group. Still, she wasn't merely a Girl

Scout trying to do good for herself and her country. For nearly a decade

she "enjoyed something of a playgirl existence. She had a prominent

Venezuelan banker for a lover and traveled the world on behalf of his

bank," Consolidado, where she was employed as a spokeswoman.

By the early 1990s Sáez had turned her energy to electoral politics.

She was motivated by a

"vocation of service" and believed she could

use her fame, her worldwide contacts, and her training in political science

to improve life in the oil-rich but impoverished nation. She won

the race for mayor of Chacao a week after the November 1992 coup

attempt. She quickly shut up critics who thought she was nothing more

than a brainless blonde. She cleaned up Chacao.

With its Baskin-Robbins stores and drive-in McDonald's, Chacao

seemed in ways like a slice of the United States in Venezuela. Nestled

in the foothills of verdant Mount Avila, it was Caracas's richest section

and home to many of the capital's diplomatic missions. But it had fallen

into disrepair. Crime was rampant, making it dangerous to head out at

night. Hold-ups by armed bandits in fancy restaurants were common.

The streets were dirty. Public plazas were falling apart.

Irene's first attack focused on the crime wave. To make the streets

safe again, she professionalized the police force. She hired university

graduates as officers, hiked their pay dramatically, and outfitted them

with the kinds of white pith helmets she'd seen British bobbies wearing

when she'd visited London as Miss Universe. She put transit officers

on golf carts dubbed "Irene-mobiles" — an idea she imported from the

Far East. She sent out other police on roller skates, mountain bikes,

and motorized children's scooters. She also bought a fleet of shiny new

police cars that cruised tree-shaded streets.

Crime plummeted. The streets filled with pedestrians at night

again. Restaurant-goers could eat out in peace. Sáez also spruced up

public squares, including Plaza Altamira, where old people took to sitting

on benches under trees sparkling with lights at night and children

roller-skated past gushing fountains that for years had been dry. The

attractive young mayor offered early-morning tai chi classes for senior

citizens, set up a paramedic team that made house calls, and improved

garbage collection. She hired top-notch administrators and listened to

their advice about everything from setting the budget to running public

services. Chacao turned into an oasis of safety, cleanliness, and cultural

life in a city where most people locked themselves in their homes at

night, the streets were filthy, and culture consisted mainly of watching

maudlin soap operas on TV. It bordered on the miraculous. People

dubbed it "Irene-landia."

Sáez was so popular by the time she ran for reelection in December

1995 that she didn't bother to mount a campaign organization. The only

person who dared to run against her, lawyer Paulo Carillo, was scolded

by his own mother and the high school he graduated from. About the

only thing Carillo could attack was Sáez's well-coiffed, stylishly dressed

figure. "She's a plastic doll," he sniffed. Sáez crushed him, taking 96

percent of the vote. It was the most lopsided victory in Venezuela's

thirty-seven years of democratic rule.

Not long into her second term, people were talking about Irene for

president. She was seen as that rarity in Venezuela — an honest and efficient

public servant. Besides, she was young, beautiful, and had a performer's

sense of how to win admirers. She donned Indian headdresses,

swiveled to salsa music, rode to ceremonies on the back of police motorcycles,

and planted kisses on old men's cheeks. Former president Luis

Herrera Campins called her "capable."

The Times

of London ranked

her among the one hundred most powerful women in the world. At

number eighty-three, she beat out Jodie Foster and Mother Teresa.

Sáez flirted with the presidential rumors, although she kept her

distance from the traditional parties Herrera Campins represented.

She didn't join any party, or form one of her own. Instead, she created

a "movement" her followers could join. She called it

Integration,

Renovation, and New Hope. In Spanish, the initials spelled out

IRENE

As the

presidential campaign entered the defining year of 1998, she was

the odds-on favorite to win, at least in the mainstream polls.

Hugo Chávez was off the establishment's radar screen. The major media

mostly ignored him, or lambasted him. He made some

missteps that provided

them ammunition. One was his relationship with the Argentine sociologist

Norberto Ceresole. An intellectual with an interest in progressive

military regimes who later moved to the far right, Ceresole was intrigued

by Chávez's coup in 1992. He sent some of his books and a card with his

telephone number on it to El Comandante in Yare. When Chávez was

released and traveled to Argentina a few months later, he called.

Ceresole was controversial. He claimed he was a member of the

Montoneros, the radical leftist and nationalist Peronist guerrilla group

that carried out a series of spectacular assaults, assassinations, and kidnappings

in the 1970s. He later argued in favor of the military coup that

overthrew Juan Perón's widow Isabel Perón in 1976 and led to a bloody

dictatorship under General Jorge Videla. Ceresole claimed human

rights organizations that criticized the abuses during Argentina's 1976

to 1983 dirty war — when the military regime killed or disappeared

at least thirty thousand people — were part of a "Jewish plot" against

the nation. He also cast doubt on whether the Holocaust had really

happened.

Despite some of Ceresole's unsavory, even bizarre viewpoints,

Chávez was attracted to him for a number of reasons. One was his early

interest in progressive military leaders. A radical Peronist, Ceresole had

written books in support of the

Peruvian general Juan Velasco Alvarado,

whose reformist government sparked Chávez's interest when he was a

cadet at the military academy in the early 1970s and traveled to Peru.

Ceresole also wrote favorably about Panama's General Omar Torrijos,

another figure who inspired the young Chávez as he sought a way to

fuse his emerging social conscience with his career as a soldier.

Ceresole considered Peronism "the most important dignifying

movement in the history of mankind." Recalling his own humble roots,

he told interviewer Alberto Garrido why:

My family did not have shoes before Peron. When Peronism

ended, we had our own house, with the loans completely paid

off. My parents had never gone on vacation. I had never been to

the sea. I was able to see it when I was ten or twelve years old.

There were vacations. They were free, absolutely free. Well, this

is called dignity.

The middle-class and the upper-class hate populism because

this means sharing. But we who come from the lower class say,

"Long live populism!" That dignifies us. When I was ten years old

I had never seen a soccer ball. I saw them in photos and Eva Peron

and the Eva Peron Foundation gave us soccer equipment, a soccer

ball, a real one. It was leather, an authentic soccer ball. And she

gave us shirts . . . and shoes.

We're talking about the people and of course, it is the mortal

enemy of the oligarchies, naturally. That's why they created the

black image of Peron, as if Peron were the son of Hitler . . . Every

dollar that we give to the people is one dollar that we won't give the

to International Monetary Fund. That's why, long live populism.

There's no other form of revolution in the Americas than that.

Chávez was attracted to Ceresole for other reasons, too. Much of

the left in Uruguay and Argentina, wary of another coup-leading military

officer after right-wing military dictatorships had devastated their

nations, closed the door to Chávez during his trip to the Southern Cone

in 1994. Ceresole was one of the few willing to meet with him. He

also had other ideas that interested Chávez, such as integrating business

and transport along some of South America's major rivers including La

Plata, the Amazon, and the Orinoco.

Most importantly, however, Ceresole offered Chávez a vision

of how to achieve and maintain power by going around the discredited

traditional political parties. It was Ceresole's celebrated triangular

notion of uniting the

caudillo

, the military, and the people. "The caudillo

would transform the military into the armed wing of a nationalist

revolutionary project and enlist the poor as its popular support base."

Ceresole believed that

the leader of such a political project would provoke a strategic

confrontation between a unipolar and multipolar world, in which

the

caudillo would face down the global hegemony of the United

States by rallying all factors hostile to US power. A multipolar

axis would emerge, involving left-wing guerrillas, progressive

social movements, and nonaligned governments in Europe, Latin

America, and the Middle East. Ceresole described his ideas as

"post-democratic," as the caudillo would sweep aside parliament,

courts, and other institutions that slowed down decision-making

processes and reined in ambitious presidential projects.

After Ceresole met with Chávez in Argentina, they reunited later

that year in Colombia. Ceresole remembered the second meeting more

for Chávez's desperate financial situation than any profound intellectual

exchanges. "He didn't have anything. There wasn't a single cent. It

was so bad we had to change hotels several times because there was no

money to pay. I'm talking about low-level hotels where we slept three to

a room . . . What Chávez was looking for at that moment was

financing,

which he couldn't find anywhere."

Ceresole accompanied Chávez as he returned to Venezuela,

crossing the border by land since he didn't have money for an airplane

ticket. The Argentine joined Chávez on some of his tours around the

country and then left for Madrid. Eventually he returned to Venezuela

in 1995. By now the government of President Rafael Caldera had

reached its limit with the controversial sociologist, and expelled him

from the country.