Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (13 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

Poor local soil was not the only reason for cities to import their food. Rome, London, Antwerp and Venice all had fertile hinterlands, yet all imported food from overseas. One reason was that imported food – as is the case today – was often cheaper than local. Sea transport cost next to nothing relative to land transport in the ancient world: one estimate puts the ratio at 1:42.

20

Even had Rome been capable of feeding itself from its own backyard, it would still have made economic sense for the city to import its grain from North Africa. As it was, cheap sea transport became so critical to the capital’s survival that Emperor Diocletian issued an edict to keep Mediterranean shipping costs artificially low, just as aviation fuel remains untaxed today by international agreement.

21

By the third century

BC

Rome already relied on grain from Sicily and Sardinia, and as the capital expanded, its conquest of new territory became paramount in order to secure fresh supplies. Feeding itself was fast becoming a vicious circle from which the city could not escape: its need for grain, not political gain, often drove its empire onward. Two military conquests, over Carthage in 146

BC

and Egypt in 30

BC

, were crucial victories, securing access to coastal North Africa, territory as vital to Rome’s survival as the American Midwest would be to London’s almost 2,000 years later. Rome lost no time in turning its new colonies into efficient bread-making machines, occupying them not just with officials and soldiers, but with farmers, 6,000 of whom were given generous portions of land in North Africa on which to grow grain for the capital.

Rome may not have been the first city to import food by sea, but the scale of its trade made it the true pioneer of food miles. By the first century

AD

, the capital was a metropolis of a million or so citizens: a quite staggering number for the time, and one that no Western city would match until London in the nineteenth century.

22

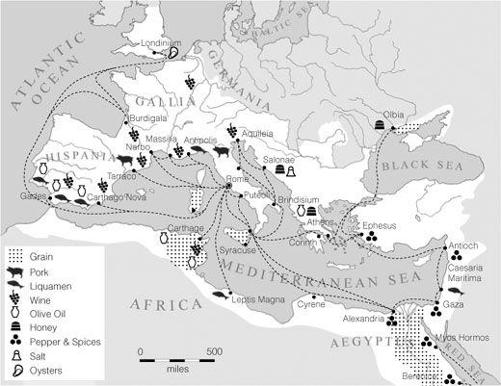

Life in contemporary London seems unthinkable without Brazilian coffee and New Zealand lamb; 2,000 years ago, the same was true in Rome of Spanish oil and Gallic ham. The entire Mediterranean sent food to the city: wine and oil came from Spain and Tunisia, pork from Gaul, honey

from Greece, and last but not least came Spanish

liquamen

, a fermented fish sauce without which no Roman’s life was apparently worth living. When the Greek orator Aristides arrived in Rome in

AD

143, he marvelled at the deluge of food flowing into the city:

… whatever is grown and made among each people cannot fail to be here at all times and in abundance … the city appears a kind of common emporium of the world … arrivals and departures by sea never cease, so that the wonder is, not that the harbour has insufficient space for merchant vessels, but that even the sea has enough, if it really does.

23

The physical and administrative effort required to bring all this fodder into the capital was truly immense. Sea transport in the ancient world might have been cheap, but it was far from straightforward. Unprotected grain could easily be spoiled in open, wooden-built ships, and winter storms often made the sea voyage too treacherous to attempt, so that grain had to be held at Alexandria, waiting for conditions to improve. Even if the ships did make a safe landfall, that was far from the end of it. The Roman port of Ostia was too small to take large Alexandrian grain ships (the supertankers of their day), so that many had to dock at Puteoli in the Bay of Naples, transferring their cargoes to smaller vessels for the trip to Rome. When food finally got to Ostia, it still had to be lugged 20 miles upstream along the narrow, swift-flowing Tiber. This final leg of the journey was the most arduous of all. It took teams of men and oxen three days to tow barges of food upriver – often longer than it had taken to complete the sea voyage from Africa.

24

The effort could never let up, even for a day – Rome gobbled up stocks of grain like sand pouring through an hourglass, and the city rarely had a comfortable safety margin to play with. When Claudius came to power, there were reckoned to be just eight days’ worth of grain left in the city.

Roman food miles. The food supply routes of Ancient Rome.

The scale of the effort can still be felt in the ancient ruins of Ostia. The Rotterdam of its day, Ostia was a thriving city of some 30,000 souls, and its theatres, temples, villas and baths are all remarkably well preserved – as are its streets, with their shops and four-storey apartment buildings above. It requires only the feeblest effort to imagine what life must once have been like here: one ancient

taberna

is so uncannily like a modern Italian bar that you have to restrain yourself from walking up and ordering a glass of wine. In the city centre, a large piazza lined with shops was once the city’s commercial hub, with merchants’ insignia – ships, dolphins, fish and the Pharos, the great Alexandria lighthouse – still visible in its mosaic pavement. But perhaps the most spectacular reminder of the scale of the capital’s appetite is the port itself: Trajan’s massive hexagonal dock, built by the emperor in

AD

98 to solve the harbour’s perennial problem of silting up. The 350-metre-long quaysides can still be made out under a tangle of brambles, and the ground crunches underfoot with shards of the amphorae that once brought oil and wine to feed the greatest city on earth.

You who control the transportation of food supplies are in charge, so to speak, of the city’s lifeline, of its very throat.

25

It was rare for any city in the pre-industrial world to leave its food supplies to chance – they were far too important for that. From the days of the earliest city-states, managing the food supply was a matter for civic authorities, a responsibility they took very seriously indeed. In the ancient cities of Egypt and Mesopotamia, temples were the food hubs of their day, combining the symbolic function of feeding the gods with the less exalted, yet equally necessary one of feeding the people.

Temples received taxes from landowners, organised the harvest, managed stocks of grain and doled them out – the latter task usually involving offering food to the gods first, before distributing what they did not take.

26

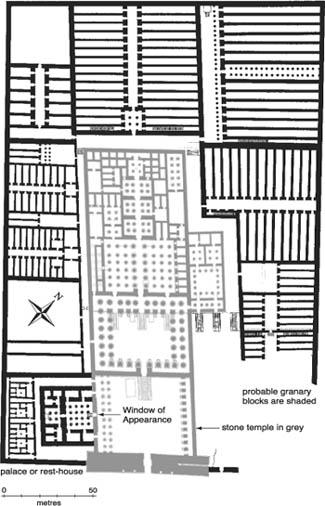

Grain was more than just food in the ancient city, it was wealth; and maintaining adequate stocks was crucial. The Ramesseum at Thebes could hold enough grain to support 3,400 families: the population of a medium-sized city. As the Egyptologist Barry Kemp remarked, such temples were not just ceremonial centres or public granaries, they were ‘the reserve banks of the time’.

27

Since Egyptian labourers were paid directly in grain and beer, the pharaohs knew by the size of the harvest just how much work could be carried out the following year.

The Ramesseum at Thebes, showing the public granaries around the temple.

Temples might have been capable of controlling food distribution in the city-states of the ancient Near East, but supplying a city the size of Rome was an entirely different matter. Not only was the population vast, but the average Roman lived in hellish conditions, in cramped

insulae

(tenements) six or seven storeys high, separated by narrow alleyways just a few feet across and with no drainage or running water.

28

Most were as cut off from the countryside as we are in modern cities, and were utterly dependent on the state to feed them. From early Republican times, the Senate provided citizens with a subsidised monthly grain ration, the

annona

, both to keep them fed and to keep them quiet: the populace lived close to boiling point, and nothing got it bubbling faster than a threat to the food supply.

Although not all Romans received the

annona

(it was limited to a privileged group of free adult males, the

plebs frumentia

), the cost of maintaining it was considerable. When the tribune Clodius had the idea in 58

BC

of securing his popularity by making the rations free, Cicero reckoned it cost Rome a fifth of all its revenue.

29

Successive emperors tried to reduce the numbers eligible, but were met with immediate rioting, and were usually forced to back down. Julius Caesar’s attempt to curb the

annona

caused bloody civil unrest that lasted until his own assassination in 44

BC

.

30

The lesson wasn’t lost on Augustus. Political animal that he was, he realised soon after taking office that, however irksome the task, feeding 320,000 citizens would prove a safer bet than trying to fiddle the numbers. It was one of his smartest moves according

to Tacitus: the historian later wrote that Augustus had ‘won over the people with bread’.

31

Nobody close to the elite in Rome could be in any doubt that food and political power were closely linked, or that failing to feed the people was the surest path to political ruin. Seventy years after Clodius’ gift to the plebs, Tiberius acknowledged his need to uphold the pledge: ‘This duty, senators, devolves upon the emperor; if it is neglected, the utter ruin of the state will follow.’

32

But even the might of Rome could not control the food supply fully. A particularly bad spate of piracy in the 70s

BC

sent grain prices rocketing, causing unrest in the city during which an angry mob attacked some consuls in the Forum. Realising the urgent need for action, the Senate nevertheless rejected an offer by the prominent general Pompey to clear the sea of pirates on the grounds that his success would give him unrivalled political power. They were soon proved right. When the people got wind of Pompey’s offer, they stormed the Senate, demanding a reversal of the decision and forcing the senators to cave in. Within weeks, Pompey had cleared the sea of pirates, causing an immediate fall in grain prices and securing him the unassailable power the senators had known it would.

33

As urban civilisation spread further north in Europe, so did its sources of supply. By medieval times, the Baltic was the new Mediterranean, and in place of the military smash-and-grab raids that characterised food supplies in the ancient world came a new, highly lucrative commercial trade.

Before the days of canning and freezing, salted herring was the unloved mainstay of many a city-dweller’s diet, particularly since the Church forbade the eating of meat on Fridays and holy days, which could amount to over 100 days a year. The demand for salted fish was such that the discovery in the Baltic of an almost unlimited supply of herring led to the formation of one of the most powerful trading cartels in history, the Hanseatic League. A treaty with Denmark had given the German city of Lübeck rights to the spawning grounds off the Swedish Scania coast, and

together with nearby Hamburg and its local salt mines, the city saw a way of turning the fish into cash. In 1241 the two cities formed a trading partnership that by the fourteenth century was exporting 300,000 barrels of salted fish all over Europe, with such impressive profits that other cities in the region such as Bruges, Riga and Danzig (Gdansk) were keen to get in on the act. The resulting Hanseatic League (from the Old High German

Hansa

, ‘group’) enjoyed a monopoly on Baltic trade until well into the fifteenth century, when a series of blows – not least the sudden migration of herring to the North Sea – began to weaken its grasp. The League’s collapse signalled the start of Dutch influence on trade in the region that can still be felt today – one based not just on herring, but on the most vital urban food of them all: grain.