I Am China (26 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

Iona is silent as Charles butters his warm scone. He surveys her pale face and heavy brow.

“I see you don’t want to follow up the matter with Milous and Snowys in your text.”

“No. Perhaps not.” She seems to confess with a sigh, “I think it’s more to do with making people intelligible. You know, Charles, translations only work because we get inside a person’s inner culture. And how does one do that? How does one get inside someone?”

Charles has his beaming, kindly eye upon her. “You have to imagine. Allow yourself to be opened up. The great translator, now and then, has to go beyond what they know. You have to go beyond translation and its techniques and tricks, and be absolutely human.”

But Iona is still not at ease. Maybe it is something about this knowing but kindly man’s gaze, like a better, kinder father looking at her. “Yes. I get all that. But it’s just not working. There’s something I’m completely missing.”

“So what is it then, Iona? It’s not translation, not intelligibility?”

“I seem to be failing here. I spend my days grappling with the real people, trying to get them to come out. But I feel like I’m not making

contact with them. It’s like, despite all my efforts to make them speak, they remain silent. Or won’t speak to me. What can I do? What am I doing? What’s the point without that connection?”

Charles draws towards Iona and rests his hand on hers. “I think, my dear, you’re talking about something else here. I don’t think it’s about translation at all. I think it’s more about you.”

5

ANNECY, FRANCE, JUNE 2012

“Take me to the French border, please,” Jian tells the taxi driver as he throws his old guitar case onto the back seat. The driver is surprised, turns his head and looks at this strange Chinese man with a large shoulder bag and big round eyes ringed with shadowy circles. The Chinese face does not waver; indeed, it seems to have no expression at all.

“A French border?” the driver questions doubtfully in English, and then says, “

Il n’y a pas de frontière française, monsieur

.”

“Then take me to the nearest French city, I have had enough of Switzerland!”

After a few seconds of silence, the North African–looking driver doesn’t bother to prevaricate. Maybe he realises that this man is not a tourist, is on no sightseeing trip. A little grumpily, he gets out and picks Jian’s guitar case up off his clean back seat and puts it in the boot—he doesn’t want his leather upholstery scratched. He starts the engine and they move off.

In no time at all the taxi takes Jian across into French Annecy. To Jian’s surprise, there is no discernible border, no wires, no soldiers, no sign, no announcement, just a motorway connecting the two countries. So this is Europe! I am in Europe! And Europe has no borders.

The driver halts in Annecy’s city centre, in front of a large Carrefour supermarket, and turns his head to announce:

“Voilà, monsieur. Vous êtes en France.”

France! Getting out of the car, Jian pays the man the meter fee plus another ten euros as thanks. Carrying his shoulder bag and his old guitar, he speaks to himself, as if in a rap: “Now I am a FREE man.

No address, no bank account, no money, no family, no friends, no more persecution, no more protection. Absolutely free. Nothing to lose, nothing to gain, as I am a free man!” He laughs out loud.

For a few days he wanders around Annecy getting his bearings. He takes his guitar and sits in a square off one of the main streets and begins to play. He sings in a low voice, an old song. But soon a gendarme appears and asks him to move on. Jian doesn’t protest. He moves through the cobbled streets. Everywhere feels like a suburb. Everywhere feels provincial, everywhere feels like hell for a Beijinger who is used to life in a lively city of twenty million. Mont Blanc and the Alps are always in view. It gives his day-to-day life a surreal penumbra, like the city is surrounded by an infinite sea of mountains. Nights pass on a bench in a park; days arrive with new hope. Then he walks into a local restaurant and finds himself a job. Labour should help him, he thinks; help both his wallet and his mind. The Chinese takeaway will be his re-education camp in the West.

6

ANNECY, FRANCE, JUNE 2012

In the Blue Lotus, there are two chefs working in the basement kitchen, both from Canton Province. They are long-married, with grownup children. The two girls upstairs serving the customers are of course their daughters or some relative’s daughters. Perhaps, for Chinese people, all social life starts with the kitchen, and everything else takes its course from there. But even so, in Jian’s eyes, they don’t seem to be very good cooks. In fact, the Blue Lotus has a terrible reputation. They use loads of MSG and recycle the oil from old dishes; their bok choi are refrigerated for nearly six months; their instant noodles expired three years before; they’ll use any old rot to cook with as long as it has a bit of grease in it. The first time Jian sits with the other workers and eats a potato dish on the menu, he is shocked. This is a typical yi-ku-si-tian dish— —a dish from the famine time, a dish that reminds him of all the miserable days he has had in his life. Not a dish of freedom. He thinks of England and the wretched pie and mash he ate when he first arrived in London, staying in a poky flat near Mile End station, and the tasteless jacket potatoes topped with greasy butter he ate in Lincolnshire. It’s strange that his food fantasies take him in this direction. He can’t help hating these overseas attempts at making Chinese dishes. Obviously, the chefs have had their hearts eaten by money, foreign money.

—a dish from the famine time, a dish that reminds him of all the miserable days he has had in his life. Not a dish of freedom. He thinks of England and the wretched pie and mash he ate when he first arrived in London, staying in a poky flat near Mile End station, and the tasteless jacket potatoes topped with greasy butter he ate in Lincolnshire. It’s strange that his food fantasies take him in this direction. He can’t help hating these overseas attempts at making Chinese dishes. Obviously, the chefs have had their hearts eaten by money, foreign money.

But it’s not the food that makes the customers vomit in Blue Lotus. It’s the stale tinny music that’s played all day long: romantic Hong Kong ballads, second- or even third-hand imitations of Western pop rubbish:

huan huan xi xi, huan you xi

. And so on and so on. It all curdles in his head as Jian chops dried cabbage and frozen cucumbers mercilessly into pieces, and splits carrots into twos and fours, and strips spring onions of their souls. He casts it all into a never-washed wok or a

boiling cauldron, to be melded into shapeless, flavourless oblivion. No wonder business has been so bad, with music like that.

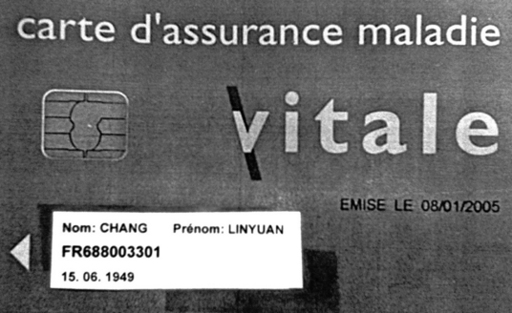

But despite the irritations of the Blue Lotus, Jian is grateful to be there, and indebted to one of the chefs in particular—Chang Linyuan.

“I have had enough here, Jian, enough.” Chef Chang opens his bearded oily mouth in his smoke-damaged face and tries to persuade Jian to go back to China. “Zhong Guo—that’s the only place in the world you can live with some dignity and speak like a sensible man.” Jian hasn’t told his new workmates the whole story, Chef Chang doesn’t know Jian can’t just go back.

He carries on. “Jian, one day you will grow as old as a pickled egg, like me. And let me tell you—Europe is not for old men!” Chang shakes his head in desolation. “There is no more reason for me to stick around here waiting for the Buddha to turn up one day. And my children are all grown up and have their own lives.”

No wonder, if the chef himself eats so badly every day—there is indeed no reason to stick around in the West waiting for the Buddha to perform some miracle. Jian swears silently with aching teeth and a pained stomach. In the last few days he has eaten nothing but rice with soy sauce.

There is a TV in the Blue Lotus which receives a Hong Kong news channel. That is the only entertainment the Chang family have for their leisure hours. The Alps stand proudly in the European wind only one and a half miles away, but it seems that the snowy peaks and cosy chalets have nothing to do with these yellow people. Nor have they ever climbed even the most modest foothill, let alone the most famous European mountain. “Not fun there, too lonely.” It’s as simple as Chang says.

Chang Linyuan has been preparing his return to China for a few months, and he has successfully transferred his savings to a Chinese bank in his province so he can buy a piece of land. One night, after

the clients are gone and half a bottle of rice vodka swills in his stomach, Chef Chang starts treating Jian like a younger brother. He opens his wallet and takes out a plastic card with a string of numbers printed on it. He speaks as Confucius might.

“Young man, I know you don’t have papers. I too had nothing for years, in the beginning. You see this piece of plastic? Keep it! It’s my French health insurance card—it will help you!”

Jian doesn’t say a word; he brings the plastic card up to his face and looks closely at the letters written on it.

“A leaf is bound to return to its roots; a man is bound to his homeland! When I return to China I’ll buy a little house in Guangzhou and I will brew my tea and feed the sparrows in my garden, go fishing, play chess and grow my own vegetables.” The chef speaks drunkenly, in a snaking Cantonese accent, appealing to Jian with his muddy little eyes.

Jian nods his head to show his respect for the old man, still studying the name printed on the card:

From that night on, Jian carries Mr. Chang’s health insurance card with him wherever he goes—he has even made two photocopies. Surely this is going to be useful, he thinks. He recites his new name like he’s

accepting his personal karma—

Chang Linyuan, aka William Chang. Numéro de carte d’assurance maladie: FR688003301

.

William Chang is going to make a living in Paris, that’s it. Like Picasso used to do, like Van Gogh, like Jim Morrison. Paris, that’s where Kublai Jian, aka William Chang, is headed.

7

PARIS, JUNE 2012

Number 141 rue Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, a windowless basement room under the Hotel Esmeralda. It’s not really part of the hotel, it’s where they store the extra bedding, toilet products and all kinds of cleaning equipment. The corners are piled with old curtains, old mattresses and old carpets. The air is stagnant, and a strong smell of ammonia lurks everywhere. Remembering something he learned in a high-school science lesson, Jian fetches a basin of water, and puts it right in the middle of the room, to test the alkaline reaction. But there are barely more than four or five bubbles as the pH dissolves. Probably this type of gas prefers to stay in Jian’s head rather than enter the water.

A fly has been stuck in my room for more than a week now. There are no windows in my basement, just a dark narrow staircase leading up to the ground floor and entrance

.

Rain is pouring down outside. Water is dripping everywhere, from the Parisian roofs to the sewage flowing in pipes under my floorboards. But how did this little fly manage to live here for weeks without seeing any light at all? Perhaps it was born from the sewage under my feet. She’s large, with a dark, heavy head between two transparent wings, and is always making this buzzing noise. Twenty-four hours a day. I think of that William Blake poem I read once at college:

Little Fly

,

Thy summer’s play

My thoughtless hand

Has brushed away

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?”

Later that night … I looked for the fly. I’ve decided that I’ll either kill her or let her out through the doorway. But she is nowhere to be found and I realise I miss her low hum

.

This morning when I woke up, the first thing I did was to look out for her, my large-headed one. There is absolutely no trace of her. Not in the toilet, not buzzing around the kitchen sink, not on the ceiling, not on the floor. Where did she go? Did she starve to death? Was she exhausted from being imprisoned here? She must be dead. I walk around the room, open the garbage bag, bring out a rotten banana. I expose the drooping banana on the floor. A fly would understand this, old bastard sky

.