I Am in Here (15 page)

Authors: Elizabeth M. Bonker

I only want to go there

When I need a break!

Sometimes I feel that the world is moving so fast I can't keep up. It is so overwhelming at times. I do find myself shutting down at these times, and I want to be alone

.

Not surprisingly, Pop loved people and would take the time to chat with those who crossed his path in life, particularly cashiers and waiters. I remember holding his large, calloused hand and walking to the penny candy store on Sunday mornings in the summertime. Ten cents would fill the small, brown paper bag with licorice, Tootsie Rolls, and gum. I suspect I got an extra piece of licorice because everyone loved Pop.

I was not surprised to read in the

Wall Street Journal

a few years ago that adults recall these simple one-on-one times as their most special childhood memories. It's not the big family ski vacation. It's reading a book with your grandpa. It's dinner out with your mom.

It's difficult to create these moments with Elizabeth. She has trouble sitting still and often doesn't want to be touched at all. On those rare occasions when she lets me hold her and sing a song or read a story, the time could not be more special. I've learned to savor these moments in the midst of the turmoil.

One of our special memories is the annual pilgrimage to the land of Mickey. Every year we request to stay in the same room at the Polynesian Resort, next to the pool with the volcano slide. Sameness is comforting for children with autism. Disney has made its parks workable for autism families by providing handicapped passes. Sometimes we get angry looks when Elizabeth and Charles bound down the handicap ramp, but waiting in line is just not possible for them.

Â

Disney World

Â

Disney Worldâthe place to be.

Lots of fun for my family and me.

Happy memories to remember and share

With the people who were not there.

That is my happy place. I love spending time with my family here. It is a trip where I can anticipate the events. It is a tradition. I feel comfortable with traditional family trips

.

In spite of those moments of peace in the Polynesian pool, the turmoil of autism ruled our lives. Ray “retired” from an exciting Wall Street career and gave up many of his Harvard dreams after we burned through seven nannies in two months. We measured their endurance in days. I remember one of them saying, “I don't know what's wrong with these kids. I say, âCharles, Elizabeth, come here,' and they run the other way.”

We didn't know why the children were “misbehaving” because their autism had not yet been diagnosed. One of us had to try to bring order to the chaos, and Ray volunteered.

“I have a career,” he said. “You have a commitment.”

Ray was referring to my ten-year commitment to manage the money invested in a new venture capital fund. Although he was leading a strategic technology initiative at a major Wall Street investment bank, he figured his colleagues could get by without him. If I quit, my investors would be abandoned.

These agonizing choices lie at the heart of any family's struggle with autism. The question is never who sacrifices but rather how will the sacrifices be apportioned. Ray's commitment to the kids has allowed me to keep my commitment to my investors, which in turn has given us the ability to bear the financial burden faced by all families dealing with autism.

In the dozen years since that fateful day, Ray has brought consistency for the children, allowing me the flexibility to travel for my work and for all those doctor appointments and teacher

meetings. He has also been active in a number of organizations in our community, including spearheading a bimonthly, nondenominational church service for children with special needs, called All God's Children.

The other member of our family who has been greatly affected by Elizabeth's and Charles's autism is their older sister, Gale. Currently a junior in high school, Gale excels in academics and loves playing her baritone in marching, concert, and jazz bands. Off the field, she marches to the beat of a different drummer, and we celebrate that she has found a group of quirky friends who love her. I just wish that they didn't text her so much.

Because of the needs of her siblings, Gale became independent at an early age. Despite our home being filled with ABA teachers day and night, Gale learned to do her elementary school homework without much assistance. By middle school, she was readily making her own dinner and doing her own laundry.

In order to make sure that Gale didn't get lost in the shuffle, I instituted “Gale Time” shortly after her siblings were diagnosed. On Sunday evenings Gale and I would go out to dinner. She chose the restaurant and the topics of conversation. As she got older, our Gale Time got squeezed by her time with friends. Now I joke with her, saying, “What about my Gale Time?”

As a parent, I've made a lot of mistakes, but Gale Time was

not

one of them. It gave me the precious gift of quiet time with a strong-willed child who is now a beautiful, confident young lady.

Because she sees what Charles and Elizabeth face on a daily basis, Gale has compassion for those who are different and is a natural peacemaker. She embraces her brother and sister and gracefully accepts the challenges they have brought into her life. Most seventeen-year-olds wouldn't even consider letting their fourteen-year-old brother hang out with their friends, but

Gale welcomes Charles despite his social awkwardness. I love it when they play Rock Band on our game system togetherâGale on guitar, Charles on drums, and a dozen friends singing their hearts out.

Gale sometimes joins Elizabeth and me for walks. Last summer, Elizabeth got upset during a walk around Mimi's lake, and out of frustration, she angrily grabbed my hair in one hand and Gale's hair in the other. It burned like bee stings. Trying to pry each of her fingers open, I was about to lose my temper when I heard Gale gently telling her sister, “It will be okay, Elizabeth. It will be okay.” Understanding born of love. Tears welled up in my eyes.

Most of my own childhood is a big blur punctuated by bizarre and special events, not unlike my life now as an autism mom. I remember the night that we packed up one of our four pet shops in a local strip mall. The dogs, cats, snakes, monkeys, alligators (pet shops had many exotic animals back then), rabbits, hamsters, fish, parrots, and other critters were all in a tizzy as we loaded them into the U-Haul. I guess there was some dispute with the landlord, but to my eight-year-old mind, it seemed like we were stealing our own stuff.

I have memories of my dad taking me to Las Vegas when I was ten years old. I stood on the side and counted cards while he sat at the blackjack table. Back then there was only one deck, or maybe two, in the shoe, and we had a system of hand signals worked out for hitting and holding. I remember enjoying some fine dinners from our winnings on that trip.

Fire punctuates my childhood memories. My dad loved the excitement of being a volunteer fireman in our town. He would eagerly jump out of bed when the siren blared and race to get behind the wheel of the ladder truck. Dad also liked to shoot off

fireworks, and Independence Day for us was filled with hysterics and hysteria. (The hysteria coming from my mother when a flare ended up on the roof.) One year for my birthday, dad showed up with a cake full of sparklers, which quickly turned the icing into a gray, gritty mess. In our family, the sight of a birthday cake elicits calls of “Get the sparklers!”

My dad worked hard, played hard, and, sadly, smoked too many cigarettes. He died of lung cancer at sixty-two, just months before the children were diagnosed with autism. My mom says that it was probably better that way because it would have crushed him. Although I miss him dearly and know he would have been so proud of Elizabeth's courage, perhaps it is better that he is spared the pain of this journey. And whenever Elizabeth shows her daredevil side, I have to smile because I can see my father's spirit of adventure living on in her.

Shortly after my dad's death, Mom sold their final and most successful business, an antique cooperative. Her retirement allows her to help us with the children. We try to schedule one special trip each year to thank her. Because we share a love of foreign cultures, our adventures have included Bermuda, England, a riverboat cruise down the Rhine, France, the Kingdom of Bhutan, sailing a catamaran down the Dalmatian Coast of Croatia, and a safari in East Africa. In every case Mom, just like Pop, made friends of the waiters, the bus drivers, and especially our hunky Croatian skipper.

My most special childhood memory of Mom is her reading me

Cheaper by the Dozen

. This true story of a family with a dozen children had quite an effect on my mom and, consequently, me. The Gilbreth family's father was an efficiency expert and used his methods to run every aspect of their household. Even their bathroom time was not wasted. The children were required to

turn on a tape recorder while on the toilet and learn French. By the end of the book, all the children were fluent. If you add it up, you will be surprised how much time you spend in the bathroom. You too could be fluent in French.

Mom's form of efficiency is a can-do attitude, which is my constant support in the autism fight. Ever since I was a child, she has believed in me. When I had crazy dreams of going to Harvard (my parents were woodworkers in our basement at the time), she said, “Of course you'll go to Harvard.” It didn't matter that no one in our family had ever gone to college, let alone the Ivy League. It didn't matter that they didn't have the money for college; we would find a way somehow.

Today she believes that we will conquer autism, and with her wind beneath my wings, I believe we will as well. Pop and Mom are the How People of our family. They supported my dreams, and I will do my best to pass that spirit on to Elizabeth, whatever her dreams may be.

A View from Tibet

Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.

Winston Churchill

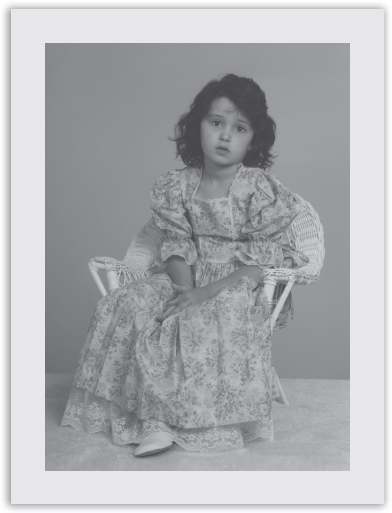

A vacant stare from my early autism days

Â

Make a Change

Â

Shades of gray

Like a cloudy day.

Things going on in the world

They make my mind whirl.

What will become of the world as we know it

If someone doesn't stand up and show it?

We need peace

And the wars to cease.

Can I be that one?

I need a voice to get it done.

(age 10)

When I wrote this poem I wanted to declare my position on war. I am for world peace. I will speak out for peace and an end to war. I plan to make a change in the world

.

I

still remember the horror on my father's face when he came home from our family's deli one night and said that a customer had heard I was telling the other children in school that I was an atheist.

To make a long and winding road short, I was raised in a nominally Christian home with a Catholic father and Protestant mother, and I fell away from my faith as a young girl when we stopped going to church. I came back to Christianity through the study of the world's other great religions. One of the most important times of my life was a year on a fellowship studying Eastern philosophies in Southeast Asia after college. As a result, you could say that my spiritual life, while Christian, is on the mystical side.

And Tibet is a mystical place.

In 1987, I found myself wandering around those enchanting mountain peaks. As I sat on the floor of the Jokhang Buddhist temple, packed among the local pilgrims, with only yak-butter candles lighting the quiet darkness, I could feel time stand still. Sometimes in the chaos of autism, I think about that stillness and try to feel that kind of peace again.

My time in Tibet made me think about how incomprehensible God is, how we can feel lost in the infinite vastness of the Maker of the universe, the One who is before time and beyond time. Tibet's snowcapped mountains are virtually untouched

by modern civilization. It's easier to feel God through nature in mountains of such vast beauty. Psalm 19:1 says, “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork” (ESV), so maybe Tibet, averaging 16,000 feet in altitude,

does

in some sense bring us closer to God in a way that standing on a stepladder couldn't.