I Am in Here (7 page)

Authors: Elizabeth M. Bonker

In our autism journey, I see it as a sign of great integrity when a doctor tells us, “I don't know.” Elizabeth is on the road to recovery, but the road is long and winding. Unlike with other ailments, the autism road is not paved or well traveled with the proven treatment options clearly marked. Parents are pushing doctors to try new treatments. Someday the science will fully catch up, but those of us who believe that autism is treatable and its impact reversible cannot wait for the seemingly endless traditional double-blind studies to pave the road. We must charge forward with hope.

On Her Own Terms

You don't have to suffer to be a poet. Adolescence is enough suffering for anyone.

John Ciardi,

Simmons Review

1962

Typing on my letterboard

Â

Silliness

Â

Over said to Under

I think we have blundered

What happens in the middle

Could put us in a fine fiddle

(age 9)

I was trying to be like Dr. Seuss.

F

rom the ages of seven to thirteen, Elizabeth has written more than one hundred poems in which she tells us about her inner world and her connection with the world around her. Elizabeth is largely self-taught as a poet, and she experiments with different forms of poetry to express herself.

Elizabeth wrote this acrostic poem about the desert:

D

ryness, dryness everywhere

E

venings always cold and clear

S

ounds echo in the night

E

very animal comes into sight

R

ising moon is in the sky

T

he owls come out to fly

This is her first Haiku poem:

Dolphins swimming near

There is nothing to fear here

They are quite friendly

While Elizabeth does her schoolwork on a laptop computer, she writes most of her poetry on the letterboard. She does not initiate communicating with us because, she has told us, it is “

tedious

.” Perhaps this is the reason she communicates her thoughts primarily through poetry.

Why is poetry the perfect medium for Elizabeth to express herself? Despite fancying that I have a muse, I'm not a poet, so I have looked to others for the answer. As it happens, the poet with the best answer lived three doors down from me when I was growing up in Metuchen, New Jersey. I didn't know of his fame at that time, but many years later, after reading his beautiful translation of Dante's

Divine Comedy

in college, I asked if I could meet with him. I still cherish the copy that he autographed for me.

The bibliophiles among you may know that I'm speaking of John Ciardi, a man who loved words so much that he wrote three books of word origins and hosted a program called “A Word in Your Ear” on National Public Radio until his death in 1986.

In his article “How Does a Poem Mean?” Ciardi recognizes that a poem's every word is precious and fraught with meaning. Most of us ask “What does this poem mean?” when a more penetrating way of asking the question is “

How

does this poem mean?” How does it build itself into a form out of images, ideas, rhythms? How do these elements become the meaning? How are they inseparable from the meaning? As Yeats wrote:

O body swayed to music, O quickening glance, How shall I tell the dancer from the dance?

A great poem is inseparable from its own performance of itself. For Yeats, the dance is in the dancer and the dancer is in the

dance. Or put another way: Where is the dance when no one is dancing it? And what man is a dancer except when he is dancing?

Just as a poem stubbornly refuses to allow itself to be summarized, so it is with Elizabeth. She can't be summarized by a diagnosis, a label, or a first or second impression. To know her is to take the time to understand her on her own terms, at her own pace, in her own words. Like art and music, poetry invites us to come to it on its own terms, at its own pace, in its own words.

So for Elizabeth poetry is the perfect vehicle, because it can't be summarized or put in a box. When asked what one of his poems meant, Robert Frost is reported to have said, “If I could have said it any more simply, I would have.” Hopefully, by reading Elizabeth's poetry, people will begin to

learn

herânot as a label or a first impression, but on her own terms. She is telling us who she is, as simply as she can. It is up to us to slow down and listen.

Â

No Acorns

Â

Today is not fall

Only green leaves

In the rain

Dear is the summer

Slow down for me

You go too fast

Stay a while

The summer was ending. I was sad.

Elizabeth's poetry evidences her human need to express her thoughts as well as her love of language. Not only do her poems enable her to unburden herself from the frustrations of autism, but like any fun-loving child, she also writes for her own entertainment.

Â

Nonsense Poem

Â

There was a pig

Who found a fig

And put it in his rig.

He went to town

And saw a clown

Who wore a frown.

“Why do you frown?”

He asked the clown.

“I hunger for a fig.”

“That's easily done.

Just check my rig.

And then we'll have some fun.”

I try to think of silly words and characters. Then I have them do human things. The reason I do this is to prove that it is nonsense. These are my favorite poems to write

.

Years later, she wrote this next poem during an evaluation with a highly regarded neurologist and her research assistant, who were trying to unravel the complexities of her extreme abilities

and disabilities. Interestingly, the poem's shape looks like a girl with her arms outstretched.

Â

Help Me

Â

Sad, lonesome, you can't believe.

See inside of me.

My soul is in pain, you see.

Help me to be who I need to be.

Teach me the way to get through each day

And not do the things that will turn people away

From me.

I sometimes get frustrated and act out before I realize what I have done. I hope to be able to better deal with my emotions so people won't be scared to be my friend or schoolmate

.

Each day when Elizabeth comes home from school, Terri and I sit with her at her desk and ask if she would like to write a poem. If the answer is no, we encourage her to think about a couple of topics for the next day. When the spirit moves her, she composes, edits, and memorizes these poems and reflections in their entirety in her head.

Elizabeth writes her poems on a letterboard, where she points out each letter without punctuation, without pauses, and without any further edits. It is a tiresome process, and we must stop numerous times to confirm with her that we have accurately

transcribed her words to paper. She is a tough taskmaster and lets us know if we bungle a single letter.

Elizabeth

is

demanding of us, and she also has an ambitious plan set for her life.

Â

My Plan

Â

Those that know me

Show me

They understand

I have a plan

To make a stand

For people like me.

Someday you will see:

An advocate I'll be!

I want to spend my life helping people. Autism is only one of the things I want to research. I also want to help the homeless, hungry, and sick people. There are people in our own country who need our help

.

Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley once wrote that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. I believe he is right. With her poetry, Elizabeth is taking a stand for those who cannot yet speak for themselves. She inspires me with her plan to help all those who are suffering, not just those with autism. Her poetry doesn't merely draw me into deeper contemplation of life's injustices. It calls me to action in overcoming them.

Looking for Ability, Not Disability

We know what we are, but know not what we may become.

William Shakespeare

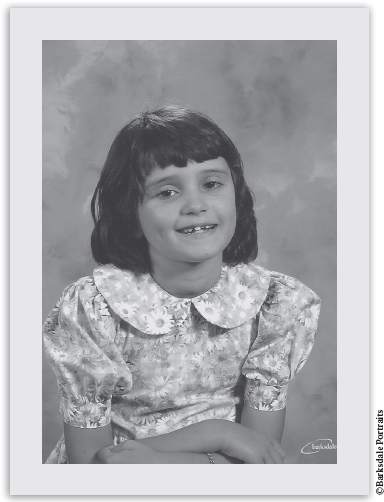

Finding my way in elementary school

Â

Upset Today

Â

I get so angry and upset

Because my expectations are not met.

I can't think of a better way

To make you see what I want to say.

I am always sorry later, trust me when I say,

I would rather have a nice day.

(age 9)

“Upset Today” was a poem I wrote after I had an extremely bad day. I am not always able to show people how I am feeling. Sometimes I am not feeling well inside, or I have a hard time focusing. Sounds or smells that bother me do not seem to be noticed at all by others. I struggle to fit in, and succeed most days, but like everyone else, I have a bad day once in a while

.

I

n every encounter is an opportunity to find a clue to help solve this autism mystery.

Several years ago I was having lunch with Simon, a friend and former business colleague, and we talked about our kids. He said that his boss had a son named Dillon who sounded a lot like Elizabeth, and he volunteered to make an introduction. Before long I was emailing with Dillon's mother, and we became fast friends. We agreed to have lunch together on my next business trip to San Francisco, and I heard Dillon's story.