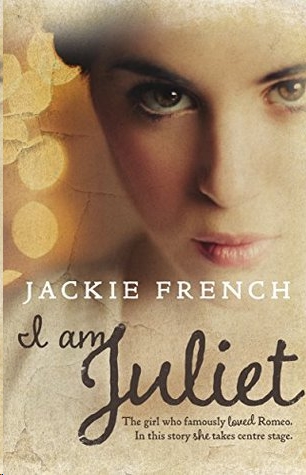

I Am Juliet

Authors: Jackie French

To Angela, with love and gratitude, and to the angels of Monkey Baa Theatre Company who continue Rob’s magic

ROB

Beare Tavern, 1592

The tavern room smelled of chamber-pots. Rob Goughe, youngest apprentice actor of Lord Hunsdon’s men, scratched a louse bite under his cap. ‘Out, damn spot,’ he muttered. A night as lousy as his hair! Black specks in the bread he suspected were mouse droppings, not currants. A pimple as big as a baked onion on his chin. And this new script of Master Shakespeare’s …

Rob stared at the paper covering the table. Words! Page after page, scribbled so fast Master Shakespeare hadn’t bothered to blot the ink. Southwark crowds didn’t want speeches. They wanted dancing bears. Sword fights! They’d throw rotten apples if the company tried to give them a play like this. Or oyster shells, which were worse.

Shakespeare should have stuck to making gloves. Gloves lasted for years. Plays vanished when the audience

left the ale-house courtyard. The company moved on to other tales, the old scripts eaten by the mice.

Aha! His fingers found the louse. Rob squashed it on the table. He picked up the manuscript again.

The Tragical History of Romeo and Juliet

. He began to read it properly, trying to see the action in between the words. If there were enough sword fights, they might get out of this without rotten egg on their faces and with a few pennies in the box.

Some jokes and a fight to begin with. Good. The more blood the better. A dozen jars of strawberry jam mixed with wine dregs and there’d be ‘blood’ smeared across the stage. Maybe this play would work despite the speeches.

He lifted the next page. No bears yet. Pity. Old Bruin dancing on his rope was always good for a laugh.

And then he saw the first line of his part, Juliet. A girl’s role. Again.

Rob sighed. He always had the girl’s role. Always would, till his voice broke. ‘Show us your merkin, darling,’ the drunks cried as soon as he minced onto the stage, trying not to trip in his long dress. ‘Let’s see your legs, darling.’

At least there were never many lines to learn. Mostly he just had to stand there and let the older actors speak. What could a girl say in the world of men? Except Queen Bess, of course. But queens were different.

Rob nodded as the girl let her mother and the nurse do the talking. ‘

Madam, I am here. What is your will?

’ Yes, he could say that in a girl’s high voice, eyes down.

He dipped a crust of bread in his ale. Another fight scene. Excellent. A banquet. That meant fine costumes, second-hand from the Earl’s household. The commons liked gaping at silks and velvets, even if the moths had eaten the fur trimmings. Maybe they could add a dancing bear at the banquet.

Now it was time for Juliet to speak again.

The bread dropped from his fingers. Rob stared at the words in front of him.

‘

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch

…’

Words of passion and determination. What was Master Shakespeare doing, giving a thirteen-year-old girl lines like this?

Rob flicked over the pages. Marry, the girl was the hinge on which the whole play turned.

‘

Then have my lips the sin that they have took

.’

He’d have to kiss Master Nicholas, in front of everyone. He’d have to stare at him with love and longing. He’d have to play a girl who defied her parents. Who proposed marriage to a boy she had just met! Who plotted to pretend to be dead so she could run away with him, all for love …

He couldn’t do it. He didn’t have the experience to play a role as big as this. What did he know of girls in love, except that they’d never been in love with him? He’d never been close to a girl, except that time up in the

hayloft and not much had happened then. His sisters had died of the plague long before they’d reached thirteen. Ma had died too, and Pa had married again, which was why he’d sold his son to be an apprentice to Master Shakespeare, to get a piece of silver in his pocket and one less mouth to feed.

He’d need to be a journeyman actor in his twenties with a share of company profits before any girl would notice him and he could be wed.

A man bellowed for a lackey to remove his boots in the room next door. Rob could hear drunks singing in the tavern below, the cries of oyster sellers, the lad offering to whip Bruin to dance for threepence. This was his world. Not back in old Verona.

Rob looked again at the parchment. So many words!

And yet, what words.

‘

My bounty is as boundless as the sea

,

My love as deep; the more I give to thee

,

The more I have, for both are infinite

…’

A breeze blew up from the river, through the rotting shutters of his window. It was almost as if he smelled roses and the taste of love amid the stench of chamber-pots, the river mud and mouldy cabbage stalks.

Suddenly he could see her. Short, like him; quiet, with eyes downcast. But inside she was a girl of fire and steel.

The night stretched into silence. The candle guttered. Even the yells of the drunks receded as he read on.

JULIET

The bloody head thudded over my garden wall at midnight. The noise woke me just as the church clock chimed twelve. Someone laughed in the street outside.

I pushed back the bed curtains. The marble floor under the rush matting was cold as I stepped out onto the balcony to investigate the noise. Nurse snored in her truckle bed behind me, loud as the carter’s horse grunting up a hill.

Moonlight lit the garden. I saw the shadowed rose bushes, the gravel paths, the high stone walls. I saw the white face of what had once been a man. Even in the moonlight I could see the blood.

I had never seen a severed head before. I had never seen a dead body. Dead bodies belonged to the world of men, beyond my garden wall.

I could smell the roses in the garden, the cold stone scent of night. Far off I heard the watchman’s cry, ‘All’s

well.’ But watchmen only patrolled those streets where all

was

well. They had not helped the man whose head lay in my small garden.

A nice girl would scream and call for help. I am Juliet Catherine Therese Capulet. I am a nice girl, or at least I can pretend to be. But sometimes my thoughts and dreams are not nice at all. I peered across the shadows. Were the murderers lurking beyond the garden wall?

I knew the dead man’s face, despite the blood, and those wide unseeing eyes. I had seen him in the crowd at the harvest feast on our estates, when my father made a present to each man in our service. A florin to a stable lad; ropes of pearls to the sea captains whose trading ships made our house rich. This man had been one of many hired to wear our livery of green and gold and to accompany members of our family through the streets, carrying his shield with a short sword by his side to make a good show and face our enemies.

Now our enemies had killed him. Montague rats had taken this man’s life.

The laughter came again, farther away now. The Montagues had dumped the head here to make the only daughter of the Capulets scream, have nightmares.

I did not scream. I did not even pull the bell rope to call for help. If I pulled the rope now, the whole house would be gossiping that young Juliet had seen a severed head, was swooning and sobbing in her room. By mid-morning

it would be about the marketplace. The Montagues would win.

I had no need of help; nor did that poor man there, though his wife, his mother, his children perhaps, would need it. We would give him revenge too. I hoped there would be Montague blood on the cobblestones tomorrow.

Girls are little use, except to marry and breed sons. My father had no son, since my brother died of the white flux when he was four. My mother’s nephew was my father’s heir now. I could not help my father fight his enemies. But I could help him hate them.

Better to pretend I had not seen that poor drained face. The house watchman would find him on his rounds. He would carry the head to rest decently with its body, wash away the necklace of blood. In the morning there would be nothing in my garden, except the echo of the laughter of the Montagues.

I slipped back into my room. I’d tell no one. Who was there to tell? Nurse, who would gossip? The maids, who would shriek? I saw my mother and my father rarely, only when they called for me. I had no friend, no sister.

So I went back to bed. I slept. I dreamed, but not of blood.

I dreamed of love.

Most dreams are shapeless. The pieces cannot be put together. These dreams were moments ripped from time.

His hair was dark. I never saw his face. I never even saw him clearly. Once, when I was five or six, I dreamed I threw my ball at him, hoping that he’d catch it. But the ball never reached him. It was as though he was on one side of a mirror and I was on the other.

I was ten when I knew that I loved him.

He would be tall, like my mother. Handsome, like my father. But even though I saw him sitting in the great square before the Cathedral, laughing with his friends, he was in shadow, so I could never quite make him out. Tonight, in my dream, I stood on my balcony. There was no bloody head among the roses. Instead, he was in my garden, shadows and laughter. I couldn’t touch him. But I could speak.

‘Goodnight!’ I whispered.

I reached out …

Nurse dropped the poker and I woke up. My dream vanished, to the place where dreams sleep when we are awake. Love vanished too. A Capulet marries for duty, not for love, except in dreams.

I glimpsed Nurse through the bed curtains, muttering to herself as she picked the poker up again and tried to get flames from the coals in the fireplace. ‘Poker, poke it, poke your nose, where are those girls?’

She blew the whistle for the servants. I heard the bustle of the maids, my Joans. Joan herself was as fat as Nurse but ten years younger. Janette was a cousin of our steward, and Joanette, the youngest, was only ten years old, her face dusted with scars from the smallpox, but not too deep. My mother would only have fair maids serving in our house; no hunchbacks or birthmarks.

Nurse lifted her skirts to warm her bare backside at the sulky flames. She glared at Joan. ‘You think this is a

fire? It’s got no more heat than a pimple on a butcher’s bum. Fetch wood, and warm water for your mistress.’

Nurse pulled back my bed curtains, leaving a thumbprint of soot for Joanette to remove later. ‘Are you awake, my little plum? And a good day it is too, if those lazy girls bring wood …’

I let her words flow over me. Nurse burbled every moment of the day till she lay down on the truckle bed at night. And then she was only silent till she snored.

I stretched on my feather mattress and waited till there was a gap in her words. ‘I’m awake.’

‘Well, up you come, my dumpling.’

I stood on the rush matting and let Nurse take off my shift. Joanette arranged the screens to stop the draught, and Joan brought a bowl of warm, rose-scented water. They washed my face, my hands, my armpits and my legs. A cloth warm from the fire to dry me; a dusting of orris root powder under my arms and across my body to make my scent sweet and soak up any sweat.

I held my arms up so they could dress me. A smock in fine white linen, a yellow silk underdress, then red sleeves pinned onto it. I lifted one leg for a cotton stocking, and then the other, then lifted them again for my silk slippers: red embroidered with green thread. Did the Joans know about the bloody head in the garden? Were the servants whispering about it in the hall? Or had the watchman disposed of the body before anyone could gossip?

They gave no sign that they knew there had been trouble last night. Joan and Janette lifted up my overgown, a loose one for a day at home, and lowered it over my head, then pinned it to the underdress.

Janette unplaited my hair, then brushed it a hundred times to keep it clean and glossy. Nurse herself plaited the thin side plaits, looped them up and then bound all my hair except the side plaits in a clean white linen coif.

I stood there as I had stood for thirteen years and let them tend me, as a nice girl should. Sometimes I thought I existed only from what they made. Was Juliet Capulet just her maids’ and nurse’s dressing, her dancing master’s skill, the years of practice of pretty phrases such as a lady used?

No, I thought. At the centre there is me, just like an apple has a core.

At last it was done. My stomach gurgled. I grinned, and felt the gloom depart. My stomach at least was mine.

Nurse laughed. ‘Listen to her! Oh, she’s always had a grumbling tummy, ever since she was a babe.’

The Joans carried in the food and set it on the table: a jug of fresh ale, which Nurse warmed by thrusting the red-hot poker into it, a tray of manchet bread still steaming from the oven, glass bowls of strawberry jelly, butter, honey, a platter of cold guinea fowl, a cheese, a chicken.

I dipped bread into the ale. It was all I wanted.

Nurse clucked her tongue. ‘That’s not enough to keep a mouse alive! A girl needs meat on her bones. Men like plump hips, my lambkin.’

If I grew any plumper, Nurse would have to let out my petticoats again. But I took the leg of chicken she handed me, and then some of the jelly with a sucket spoon. Nurse watched approvingly.

I felt someone else watching me too. I turned to see my cousin, Tybalt, in the doorway. He was tall like my mother, his blond hair shining on his shoulders. He was ten years older than I and had been part of our household as long as I could remember. A few years hence, Tybalt and I would be married. It was something we all knew, but no one talked about, like my father’s mistress or the white lead my mother put on her face to make her skin so smooth.

Tybalt was handsome, with the confidence of a man to whom fate had given everything he wanted. What it didn’t give him, he would take. He had given me a puppy, Rosemary, when I was five. When Rosemary choked on a chicken bone, he gave me a lovebird to make me smile. But the lovebird made Nurse sneeze, so now it chattered in a cage out in the garden. Once we were married, and all that was mine became his, Tybalt would probably no longer give me gifts. A husband may treat his wife how he likes. But as long as Tybalt got what he wanted, he would stay sunny. And I would do my duty, to my husband and our house.

He smiled at me, his eyes watchful, excited. So, I thought, Tybalt’s rapier tasted Montague blood last night.

His wolfhound sat at his feet. Threads of drool dripped onto the marble floor as he smelled my breakfast chicken.

Tybalt took off his hat — a new red one, with two feathers. He made me a neat bow, then came and gave me a cousinly kiss on the lips. ‘You taste of strawberries. Down, Brutus,’ he added, as the dog began to sniff my skirts.

I nodded to Janette to fill a cup of ale for him. ‘You taste of last night’s wine. Are you out late or up early, cousin?’

‘Up with the lark’s song.’ He took a chicken leg and sprawled on the cushions on the other side of the table, eyeing me and showing off his legs in green silk stockings. ‘You have an appetite for breakfast?’

His question was too casual. Brutus reached out a long red tongue and took some of the meat from his master’s fingers. Tybalt fondled his ears absently.

‘I always have an appetite,’ I said.

‘Indeed she does,’ said Nurse. ‘Oh, such a hungry one she was, even as a babe. I remember when she tore my front buttons to have her drink.’

I washed my fingers in the dish of rosewater and held them out to Nurse to dry. Little Joanette gave me a quick curtsey.

‘Yes, Joanette?’

‘My lady, have you finished?’

‘What? Oh, yes.’

I left the table so Nurse and the Joans could breakfast on my leftovers, and sat on the cushion by the window. Joanette piled her bread with meat. She had come to us starving, her whole family dead of the smallpox. She could never eat enough now.

I glanced at Tybalt, then picked up my tapestry for something to occupy my hands. ‘Well, cousin? Did you come just to share my breakfast?’

Tybalt let his wolfhound lick his fingers, then wiped them on the tablecloth. His hand shook slightly. From anger? Tybalt’s furies could last for days.

‘I would speak privily with you, cousin.’

I nodded, and stepped out onto the balcony, where the Joans couldn’t hear us. Nurse, still chewing bread and chicken, came too, as Tybalt knew she would. I had never been away from Nurse since I was first given to her to suckle. Tybalt knew Nurse would not speak of what he told me. Or rather, she would always speak, but her chatter could also cover up what she chose not to tell. I trusted Nurse as I trusted my own life.

I tried not to glance over at the garden wall where the severed head had lain. ‘What is so important?’

Once again his voice was too casual. ‘You weren’t disturbed last night?’

Disturbed? I had cried four tears, perhaps, for the dead man’s family before falling back to sleep. How could I have wept more for people I did not know?

Should I tell him that I had seen the dead man’s head?

No. Tybalt would rather be shredded by Montague rapiers than let a Montague even walk across my shadow. But I didn’t trust his temper, or his tongue. There was anger simmering under Tybalt’s smile. I didn’t want to make it worse.

‘I slept well. And you?’

He shrugged. ‘It is no matter.’

I gazed out at the rose garden, at the city’s breakfast smoke sifting up beyond our garden walls. ‘Are you going hunting today?’

‘What should I hunt?’

I had an image of a pile of bloody heads, all belonging to Montagues.

I met his eyes. ‘The Montagues. Their heads, their hearts, their hands.’

For a few heartbeats I felt part of our family, part of the feud that ruled our lives. Shared hatred tasted sweeter than apples.

Tybalt’s eyes brightened. ‘I love you, dear, sweet cousin. The Montagues will indeed be hunted today.’ He lifted my hand and kissed it, just as if I had been a woman, not a girl. ‘I will bring you the caps of two Montagues, though I will spare you the heads that bore them.’

Then he was gone. His dog followed, with a last longing look at the chicken bones.