I Have Landed (59 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

I have now done my ordinary duty as an essayist: I have told the forgotten story of the admirable Tiedemann with sufficient detail, and in his own words, to render the flavor of his concerns, the compelling logic of his argument, and the careful documentation of his empirical research. But, curiously, rather than feeling satisfaction for a job adequately done, I am left with a feeling of paradox based on a puzzle that I cannot fully resolve, but that raises an interesting issue in the social and intellectual practice of scienceâthus giving this essay a fighting chance to move beyond the conventional.

The paradox arises from internal evidence of Tiedemann's strong

predisposition

toward belief in the equality of races. I should state explicitly that I refer, in stating this claim, not to the logic and data so well presented in his published work (as discussed above), but to evidence based on idiosyncrasies of presentation and gaps in stated arguments, that Tiedemann undertook the research for his 1836 article with his mind

already set

(or at least strongly inclined) to a verdict of equality. Such preferencesâespecially for judgments generally regarded as so morally honorableâmight not be deemed surprising, except that the ethos of science, both then and now, discourages such

a priori

convictions as barriers to objectivity. An old proverb teaches that “to err is human.” To have strong preferences before a study may be equally humanâbut scientists are supposed to disregard such biases if their existence be recognized, or at least to remain so unconscious of their sway that a heartfelt and genuine belief in objectivity persists in the face of contrary practice.

Tiedemann's preferences for racial equality do not arise from either of the ordinary sources for such a predisposition. First, I could find no evidence that Tiedemann's political or social beliefs inclined him in a “liberal” or “radical” direction toward an uncommon belief of egalitarianism. Tiedemann grew up in an intellectually elite and culturally conservative family. He particularly valued stable government, and he strongly opposed popular uprisings. Three of his sons served as army officers, and his eldest was executed under martial law imposed by a temporarily successful revolt (while his two other military sons fled to exile) during the revolutions of 1848. When peace and conventional order returned,

the discouraged Tiedemann retired from the university, and published little more (largely because his eyesight had become so poor) beyond a final book (in 1854) titled

The History of Tobacco and Other Similar Means of Enjoyment

.

Second, some scientists tend, by temperament, to embrace boldly hypothetical pronouncement, and to publish exciting ideas before adequate documentation can affirm their veracity. But Tiedemann built a well-earned reputation for the exactly opposite behavior of careful and meticulous documentation, combined with extreme caution in expressing beliefs that could not be validated by copious data. The definitive eleventh edition of the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

(1910â11), in its single short paragraph on Tiedemann, includes this sole assessment of his basic scientific approach: “He maintained the claims of patient and sober anatomical research against the prevalent speculations of the school of Lorenz Oken, whose foremost antagonist he was long reckoned.” (Oken led the oracular movement known as

Naturphilosophie

. He served as a sort of antihero in my first book,

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

, published in 1977âso I have a long acquaintance, entirely in Tiedemann's favor, with his primary adversary.)

I have found, in each of Tiedemann's two major publications on brains and races, a striking indicationârooted in information that he does

not

use, or data that he does

not

present (for surprising or illogical absences often speak more loudly than vociferous assertions)âof his predisposition toward racial equality.

1.

Creating the standard argument, and then refraining from the usual interpretation: Tiedemann's masterpiece of 1816

.

By customary criteria of new discovery, copious documentation, and profound theoretical overview, Tiedemann's 1816 treatise on the embryology of the human brain, as contrasted with adult brains in all vertebrates (fish to mammals), has always been judged as his masterpiece (I quote from my copy of the French translation of 1823). As a central question in pre-Darwinian biology, scientists of Tiedemann's generation yearned to know whether all developmental processes followed a single general law, or if each pursued an independent path. Two processes stood out for evident study: the growth of organs in the embryology of “higher” animals, and the sequence of structural advance (in created order, not by evolutionary descent) in a classification of animals from “lowest” to “highest” along the chain of being.

In rough terms, both sequences seemed to move from small, simple, and homogeneous beginnings to larger, more-complex, and more-differentiated endpoints. But how similar might these two sequences be? Could adults of lower animals really be compared with transitory stages in the embryology of higher creatures? If so, then a single law of development might pervade nature

to reveal the order and intent of the universe and its creator. This heady prospect drove a substantial amount of biological research during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Tiedemann, beguiled by the prospect of discovering such a universal pattern, wrote that the “two routes” to such knowledge “are those of comparative anatomy and the anatomy of the fetus, and these shall become, for us, a veritable thread of Ariadne.” (When Ariadne led Theseus through the labyrinth to the Minotaur, she unwound a thread along the path, so that Theseus could find his way out after his noble deed of bovicide. The “thread of Ariadne” thus became a standard metaphor for a path to the solution of a particularly difficult problem.)

Tiedemann's densely documented treatise announced a positive outcome for this grand hope of unification: the two sequences of human fetal development and comparative anatomy of brains from fish to mammals coincide perfectly. He wrote in triumph:

I therefore publish here the research that I have done for several years on the brain of the [human] fetus.  . I then present an exposition of the comparative anatomy of the structure of the brain in the four classes of vertebrate animals [fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals in his taxonomy]âall in order to prove that the formation of this organ in the [human] fetus, followed from month to month during its development, passes through the major stages of organization reached by the [vertebrate] animals in their complexity. We therefore cannot doubt that nature follows a uniform plan in the creation and development of the brain in both the human fetus and the sequence of vertebrate animals.

Thus, Tiedemann had reached one of the most important and most widely cited conclusions of early-nineteenth-century zoology. Yet he never extended this notion, the proudest discovery of his life, to establish a sequence of human races as wellâalthough virtually all other scientists did. Nearly every major defense of conventional racial ranking in the nineteenth century expanded Tiedemann's argument from embryology and comparative anatomy to variation within a sequence of human races as wellâby arguing that a supposedly linear order from African to Asian to European expresses the same universal law of progressive development.

Even the racial “liberals” of nineteenth-century biology invoked the argument of “Tiedemann's line” when the doctrine suited their purposes. T. H. Huxley, for example, proposed a linear order of races to fill the gap between apes

and humans as an argument for evolutionary intermediacy: “The difference in weight of brain between the highest and the lowest man is far greater, both relatively and absolutely, than that between the lowest man and the highest ape.”

But Tiedemann himself, the inventor of the basic argument, would not extend his doctrine into a claim that variation within a species (distinctions among human races in this case) must follow the same linear order as differences among related species. I can only assume that he demurred (as logic surely permits, and as later research has confirmed, for variations within and among species represent quite different biological phenomena) because he did not wish to use his argument as a defense for racial ranking. At least we know that one of his eminent colleagues read his silence in exactly this lightâFor Richard Owen, refuting Huxley's claim, cited Tiedemann with the accolade used as a title to this essay:

Although in most cases the Negro's brain is less than that of the European, I have observed individuals of the Negro race in whom the brain was as large as the average one of Caucasians; and I concur with the great physiologist of Heidelberg, who has recorded similar observations, in connecting with such cerebral development the fact that there has been no province of intellectual activity in which individuals of the pure Negro race have not distinguished themselves.

2.

Developing the first major data set and then failing to notice an evident conclusion not in your favor (even if not particularly damaging, either)

.

When I wrote

The Mismeasure of Man

, published in 1981, I discovered that most of the major data sets presented in the name of racial ranking contained evident errors that should have been noted by their authors, and would have reversed their conclusions, or at least strongly compromised the apparent strength of their arguments. Even more interestingly, I found that those scien-tists usually published the raw data that allowed me to correct their errors. I therefore had to conclude that these men had not based their conclusions upon conscious fraudâfor fakers try to cover up the tracks of their machinations. Rather, their errors had arisen from unconscious biases so strong and so unquestioned (or even unquestionable in their system of beliefs and values) that information now evident to us remained invisible to them.

Fair is fair. The same phenomenon of unconscious bias must also be exposed

in folks we admire for the sagacity, even the moral virtue, of their courageous and iconoclastic conclusionsâfor only then can we extend an exposé about beliefs we oppose into a more interesting statement about the psychology and sociology of scientific practice in general.

I have just discovered an interesting instance of nonreporting in the tables that Tiedemann compiled to develop his case for equality in brain sizes among human races. (To my shame, I never thought about pursuing this exercise when I wrote

The Mismeasure of Man

, even though I reported Paul Broca's valid critiques of different claims in Tiedemann's data to show that Broca often criticized others when their conclusions denied his own preferences, but did not apply the same standards to “happier” data of his own construction.)

Tiedemann's tables, the most extensive quantitative study of variation available in 1836, provides raw data for 320 male skulls in all five of Blumenbach's major races, including 101 “Caucasians” and 38 “Ethiopians” (African blacks). But Tiedemann only lists each skull individually (in old apothecaries' weights of ounces and drams), and presents no summary statistics for groupsâno ranges, no averages. But these figures can easily be calculated from Tiedemann's raw data, and I have done so in the appended table.

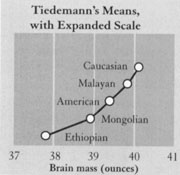

Tiedemann bases his argument entirely on the overlapping ranges of smallest to largest skulls in each raceâand we can scarcely deny his correct conclusion that no difference exists between Ethiopians (32 to 54 ounces among 38 skulls) and Europeans (28 to 57 ounces for a larger sample of 101 skulls). But as I scanned his charts of raw data. I suspected that I might find some interesting differences among the means for each racial groupâthe obvious summary statistic (even in Tiedemann's day) for describing some notion of an average.

Indeed, as my table and chart show, Tiedemann's uncalculated mean values do differâand in the traditional order advocated by his opponents, with gradation from a largest Caucasian average, through intermediary values for Malayans, Americans (so-called “Indians,” not European immigrants), and Mongolians, to lowest measures for his Ethiopian group. The situation becomes even more complicated when we recognize that these mean differences do not challenge Tiedemann's conclusion, even though an advocate for the other side could certainly advertise this information in such a false manner. (Did Tiedemann calculate these means and not publish them because he sensed the confusion that would then be generatedâa procedure that I would have to label as indefensible, however understandable? Or did he never calculate them because he got what he wanted from the more obvious data on ranges, and then never proceeded furtherâthe more common situation of failure to recognize potential interpretations as a consequence of unconscious bias. I rather suspect the second scenario, as more consistent with Tiedemann's personal procedures and the actual norms, as opposed to the stated desirabilities, of scientific study in general, but I cannot disprove the first conjecture.)

Tiedemann's means, with Expanded Scale